Among stock traders, there's an old English saying that invariably gets trotted out every year at this time:

"Sell in May and go away, and come on back on St. Leger's Day."

The adage has staying power across numerous stock markets, where major indices like the Dow Jones Industrial Average (Index: DJI) have track records of delivering more lackluster returns for stocks held between the months of May and October than they do during the the other six months of the year.

In practice however, serious analysts have not found much strong evidence to back up such a seasonal pattern over the long run.

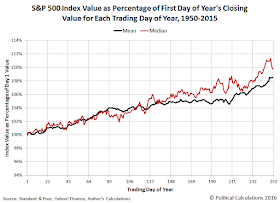

We did however come across some evidence to support it, which can be seen in the following chart showing the average trajectory and the median trajectory of the S&P 500 (Index: INX, or SPX) for all 65 years of daily data from 1950 through 2015, where each trading day's closing value for the index was calculated as a percentage of the closing value for the index on the first day of trading in each year.

If you pay close attention to the black line indicating the average trajectory of the S&P 500, you can see that it grows through the first four months of the year (through Day 85), before flattening out during the next six months (through Day 211), before rising sharply in the last two months of the year.

Now compare that trajectory with the red line indicating the median trajectory for the S&P 500 during the year. The median trajectory shows a general upward trend throughout the year without the same seasonal pattern suggested by the average trajectory.

So which of these "typical" trajectories is correct?

The answer comes down to the difference in definition between "average" (or mean) and "median". In calculating an average value, the result can be greatly affected by what might be considered to be outlier data, where an example might be if you considered the incomes of 10 random people waiting in line to buy coffee at a Starbucks (Nasdaq: SBUX), where one of the people in line turned out to be Lebron James.

With an annual paycheck of over $30 million, which is far above the incomes earned by the vast majority of Americans, including James' income in the calculation of the average income for the 10 people standing in line to get coffee would greatly skew the resulting average toward his end of the income-earning spectrum, to the point where it would not be representative of the incomes earned by the other nine people in line.

By contrast, the median will fall exactly in the middle of all the incomes of those standing in line, where 50% of the people in line will have higher incomes, and 50% will have lower incomes.

The "Sell in May" stock trading strategy only appears to hold for the average trajectory for the S&P 500 because it has been skewed by statistical outliers that were recorded during just a handful of years, both to the high and low ends of the extremes for trading in the years in which they occurred.

Does that mean that investors never have to consider the potential for having such an outlier year for stock prices?

Obviously not, because occasional outliers are very much part of the potential for volatility in the stock market. Next Monday, when we wrap up the stories that provide the context for how the S&P 500 behaved during Week 2 of May 2017 (when this link will become active), we'll consider a realistic scenario where the "Sell in May" stock trading scenario might actually be valid for investors to consider acting upon in the very near future.

As an early spoiler, it won't have anything to do with it being May, that will just be coincidental, but should it come to pass, you can count on hearing the "Sell in May" stock trading adage every year for another several decades.

Data Source

Yahoo! Finance. S&P 500 Historical Prices, 1 January 1950 through 31 December 2015. [Online database]. Accessed 11 July 2016.