Let's start today with an excerpt from an abstract published by Edwin Elton, Martin Gruber and Mustafa Gultekin during the dark ages of stock price theory, back in September 1981.

It is generally believed that security prices are determined by expectations concerning firm and economic variables. Despite this belief, there is very little research examining expectational data....

We're pointing this particular passage out because it summarizes how little work had been done to connect the dots between expectations and stock prices as recently as just over 30 years ago, despite the understanding by academics and market observers that such a connection actually exists. Let's next take a look at an early paper by Robert Shiller, which was almost contemporarily published in June 1981.

A simple model that is commonly used to interpret movements in corporate common stock price indexes asserts that real stock prices equal the present value of rationally expected or optimally forecasted future real dividends discounted by a constant real discount rate. This valuation model (or variations on it in which the real discount rate is not constant but fairly stable) is often used by economists and market analysts alike as a plausible model to describe the behavior of aggregate market indexes and is viewed as providing a reasonable story to tell when people ask what accounts for a sudden movement in stock price indexes. Such movements are then attributed to "new information" about future dividends. I will refer to this model as the "efficient markets model" although it should be recognized that this name as also been applied to other models.

What Shiller is specifically referring to at this point is the the work that Eugene Fama had done in the 1960s and 1970s to introduce the idea of efficient capital markets, which holds that "security prices at any time 'fully reflect' all available information."

The reason why Shiller was referencing the efficient markets model was because he observed that the movements of stock prices were "too volatile" to be accounted for in the subsequent changes of dividends. Or rather, as Shiller would argue, volatility in stock prices were not adequately explained by rationally expected future dividends, and because of that, investors had to be behaving irrationally for stock prices to be as volatile as they appeared.

Amusingly, despite this fundamental disagreement, both Shiller and Fama would share the 2013 Nobel Prize in economic sciences with Lars Peter Hansen for their collective work in "laying the foundation" for understanding how asset prices are set.

The truth is that they both screwed it up. Fama's efficient markets model simply isn't sophisticated enough to account for the observed volatility of stock prices and Shiller's reliance on the "irrationality" of investors to account for such volatility is simply misplaced.

Where Fama's efficient markets theory falls short is in missing is the time variance aspect of future expectations in setting stock prices. Instead of investors calculating some sort of net present value of the entire stream of future dividends they might rationally expect to earn from owning equities, we've observed that investors actually heavily weight changes in the growth rate of dividends that are expected to be earned at specific points of time in the near future.

But when investors suddenly shift their attention from one point of time in the future to a different point of time in the future, volatility in stock prices will result if there are differences between the changes expected in the growth rate of dividends for the different points of time in the future.

Shiller's fundamental error lies in attributing this volatility to investor "irrationality". Investors can have very rational reasons for suddenly shifting their attention from one point of time in the future to another, such as if firms announce changes in their dividends that will take effect in a particular future quarter or for other factors that might affect the amount of dividends they might pay in the future, such as changes in interest or tax rates.

In any case, what we just described pretty much accounts for all of the variation and volatility in stock prices in 2014.

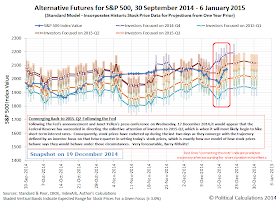

Here's a link to the math we invented that converts these changes in growth rates for dividends into changes in the growth rate of stock prices, and the chart below shows the results we get when we applied that math in our standard model for each future quarter for which we had expected future dividend data throughout the fourth quarter of 2014.

For the CBOE's dividend futures data, the value of the constant, m, in our math is approximately equal to 5. If you use Indexarb's bottoms-up dividend futures data, the value of the constant is approximately equal to 9.

Why are we telling you all this? Well, after six years of development following our initial key insight into the nature of how expectations for dividends actually drive stock prices, where the last several years were required to accumulate a sufficient amount of dividend futures data just to validate our theory that largely reconciles the discrepancies in both Fama's and Shiller's work, we're retiring this stream of analysis since it is no longer under development.

Someday, we hope this explains how some obscure blogger managed to get into the line where they hand out Nobel prizes in economics. Until then, because we did all of our development work in public, almost entirely from scratch and without a safety net, you have more than enough information to apply our theory on your own.

So go have fun! There's certainly a lot more possible today because of our work in just the last six years than there was in all the decades that preceded it.