When multi-billion dollar firms seek to merge, the temptation to use every means possible to attain approval from regulatory authorities and realize tremendous financial gains can lead to some really questionable claims being advanced to achieve that end.

Today's example of junk science is our second where pseudoscientific practices have had real world legal implications. In this case, the discussion revolves around the situations that arose when pseudoscientific econometric analysis was presented by firms seeking the U.S. Department of Justice's Antitrust Division's approval to merge their businesses, but which was instead detected by the division's staff economists and subsequently challenged by the division's attorneys in legal proceedings.

Here are the relevant items that apply from our checklist for detecting junk science that come to play in today's example.

| How to Distinguish "Good" Science from "Junk" or "Pseudo" Science | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Science | Pseudoscience | Comments |

| Goals | The primary goal of science is to achieve a more complete and more unified understanding of the physical world. | Pseudosciences are more likely to be driven by ideological, cultural or commercial (money-making) goals. | Some examples of pseudosciences include: astrology, UFOlogy, Creation Science and aspects of legitimate fields, such as climate science, nutrition, etc. |

| Inconsistencies | Observations or data that are not consistent with current scientific understanding generate intense interest for additional study among scientists. Original observations and data are made accessible to all interested parties to support this effort. | Observations of data that are not consistent with established beliefs tend to be ignored or actively suppressed. Original observations and data are often difficult to obtain from pseudoscience practitioners, and is often just anecdotal. | Providing access to all available data allows others to independently reproduce and confirm findings. Failing to make all collected data and analysis available for independent review undermines the validity of any claimed finding. Here's a recent example of the misuse of statistics where contradictory data that would have avoided a pseudoscientific conclusion was improperly screened out, which was found after all the data was made available for independent review. |

| Models | Using observations backed by experimental results, scientists create models that may be used to anticipate outcomes in the real world. The success of these models is continually challenged with new observations and their effectiveness in anticipating outcomes is thoroughly documented. | Pseudosciences create models to anticipate real world outcomes, but place little emphasis on documenting the forecasting performance of their models, or even in making the methodology used in the models accessible to others. | Have you ever noticed how pseudoscience practitioners always seem eager to announce their new predictions or findings, but never like to talk about how many of their previous predictions or findings were confirmed or found to be valid? |

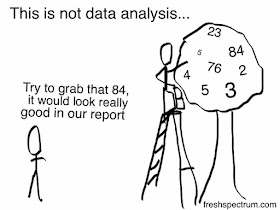

While the goal of commercial gain clearly identifies the motive behind the pseudoscience that will be discussed, the actual mechanisms by which it was carried out involve the cherry picking of data favorable to the parties seeking to merge their companies and the models they selectively presented to claim the proposed mergers would not negatively impact consumers.

Like good detective stories, it can make for fascinating reading. Today's story picks up below, with the recognition of the contributions that economists are making to the DOJ's antitrust division, before getting into how attorneys consider the data and analysis contributed by economists. We've emphasized a number of key points in boldface type....

Economists play a vital role in every significant merger investigation and litigation we handle. They have the expertise and facility to extract from mountains of raw data a variety of useful measures such as sales volumes, revenues, margins, market shares and others. They review bid data to determine the frequency with which companies encounter each other in the market, the closeness of competition and whether bidding behavior is characterized by coordination. They help us understand how competition works and how data can be used in assessing competitive constraints and predicting the likely impact of a merger. They develop theories of harm that not only guide their own quantitative work but also inform the work of lawyers who pursue the non-quantitative evidence on which cases rely. They also have a seemingly endless supply of lawyer jokes.

It would be impossible for me to list the many times and the many ways in which economists have helped me better understand the matters I have worked on at the division. They have predicted price increases in transactions across a variety of industries. They have modeled competitive effects for commodity products where price is determined by output decisions of suppliers. They have shown how mergers can give parties increased bargaining leverage, in industries ranging from cable and internet to healthcare. They have assessed party arguments about efficiencies and alleged mitigating effects in two-sided markets. To name just a few.

But I am not here simply to congratulate the profession for all its fine work. If hourly rates are any indication, you already know how valuable you are. I would also like to share a few candid thoughts about some of the economic evidence I have seen presented to the division. I am providing these observations from the perspective of a lawyer involved in merger decisions and litigation. My colleagues in the Economics Analysis Group undoubtedly have additional thoughts on these topics.

To begin with, you should understand that your primary audience when presenting economic evidence to the division consists of our economists. You need to demonstrate to them that your work is valid, that the data are reliable and that your conclusions are supported by accepted methods of economics. I can assure you that if our economists are not convinced, it is extremely unlikely that the legal team will second guess them on the economic work. I have been in front office meetings when arguments have broken out between the parties’ economists and ours. That is not where you want to be.

Second, when presenting to the lawyers at the agency, you need to be able to explain in simple terms the nature of the work you have done, the source of the information that feeds into that work and why it demonstrates the point you are trying to make. It is not persuasive to rattle off technical jargon and expect us to take on faith that a conclusion is valid simply because you obtained some value for a statistic. We need to understand the intuition behind the work and the basis for the results. Note also that if we can’t understand it at the agency, you should not expect to be able to explain it to a generalist federal judge who might have little or no experience with antitrust cases or merger challenges.

While we are on the topic of simple explanations, I believe the economic literature needs to become more accessible to non-economists. There is a problem that some in the profession have referred to as “mathiness” in economics. You write articles for each other, not for the rest of us. I can’t tell you how many times I have picked up a paper written by a leading economist on an important antitrust topic, generally absorbed the gist of the abstract and the introduction, then turned the page only to be confronted with complicated equations and a discussion I could not follow. Obviously scientists must devote considerable time explaining their work to each other and debating the merits of that work in terms the rest of us can’t be expected to grasp. But if the science is to be influential with lawyers who make enforcement decisions and with courts, there need to be sources to which we can turn, written professionally and by respected experts in the field, that provide clear explanations.

Third, I cannot emphasize strongly enough how important candor and credibility are in presenting economic evidence, just as it is with all interactions parties might have with the government or the courts. If your methodology is sound and the data support your conclusion, you shouldn't need to pull a fast one on us. Conversely, if you try to pull a fast one, we assume either the methodology is unsound or your conclusion is not supported. I offer two examples, one small and one large.

I recall sitting in a front office meeting receiving a presentation from the parties on a merger that was a close call. One of the pieces of economic evidence that was presented was a before-and-after study. The results were shown in the form of graphics to demonstrate that a particular event had not impacted a variable of interest. It was an impressive point. But then something caught my eye. In very small font beneath each graph was a listed data source. The data source for the “before” graph was different from the data source for the “after” graph. One was an objective third-party source and the other was described simply as the economist’s estimate. Of course I became immediately suspicious of the validity of this study. The parties had an explanation when asked and maybe it would have been credible if it had been volunteered upfront, but it raised a significant doubt in my mind. We ultimately cleared the transaction but, at least speaking for myself, that part of the presentation played no role in my thinking. This is the small example.

The other example I have in mind involves a regression model that purported to show that a prior transaction in the same industry but involving different products had no effect on prices. The model suffered from a number of flaws but one of the things that most bothered me about it was that the underlying data the expert used included the actual products at issue in the transaction under review and the expert’s model yielded statistically significant results showing that prices of those products had gone up. These results were not presented in the expert’s report but were discovered only after some dogged detective work by economists at the division who reviewed the backup data. The explanation for omitting these results from the report: the economist thought they were not robust because they varied when he did alternative runs of the model, which themselves were not disclosed. Whatever debate might have been available to the parties about the robustness of the results or the significance of the parties’ own model showing an increase in prices is of no moment; this should have been disclosed and presented with candor. The transaction was ultimately abandoned.

This brings me to my fourth point. You have to give us the information we need to test and verify your economic work and you have to give us time to do the work. It is our job to be skeptical of models that are constructed by experts employed by the parties. To be sure, the work that is presented to us is often immensely helpful. I have seen it play a big role in our decisions. But we will not take it at face value. So, to take a real world example that I recall, don’t present us with a model that purports to show the market is broader than we have always viewed it in a particular line of commerce, with only one week to go before the deal has to close. It’s not realistic to expect us to take that kind of risk on behalf of consumers without having the time and the information we need to fully vet the economic evidence you are presenting. This transaction also was abandoned.

Fifth, use lots of charts and pictures when presenting to lawyers. Text slides, not so much.

Sixth, recognize that the farther you stray from known methods of studying markets and the more customized and unusual the model you present, the more skeptical we will be that it provides meaningful information. Moreover, the fact that an expert can produce a model to achieve a certain result does not necessarily help us or a court decide the case. In this regard, while I believe the quality of economic work in the field of merger enforcement is generally first rate, we do see junk science from time to time. When data are mined and variables mixed and matched in such a way that a facially helpful conclusion can be drawn from a regression, even though an alternative result can easily be obtained by tweaking the inputs, we will likely view it as biased and unpersuasive.

I recently learned a term I hadn’t heard before from an episode of Last Week Tonight with John Oliver. This episode explored how scientific studies often have little value and yet are widely reported by the news media. The term Oliver used is P-hacking and if I understand it correctly, it describes how researchers can sift through data looking for relationships that will show up as statistically significant, rather than study a hypothesis objectively. This process can produce absurd results that appear to be valid but are not. Although I never knew the word for it, this seems to capture what happens with regression models presented to us on some occasions. That is, the expert runs ten regressions, discards nine unfavorable or insignificant results, and keeps the one that is favorable and significant. Don’t p-hack. It wastes time, it will be vulnerable to cross-examination and it undermines the legitimacy of the valuable contributions that economics can make to a case. As an aside, it also provides material for us lawyers to make economist jokes.

Finally, I believe economic evidence is best viewed as a complement to the other evidence in a case, not as a substitute for it. If the non-economic evidence points strongly in one direction, it is highly unlikely that a regression model pointing in the other will save the day. I don’t believe I have seen it happen in my three years at the division.

Moreover, it is wise to bear in mind that courts will be strongly influenced by the non-economic evidence. Opposing economic experts are both likely to be highly qualified professionals with many years of experience, a long list of impressive publications and an ability to recite various statistics that support their respective points of view. Confronted with such a battle of the experts, judges tend to look to other sources of evidence in deciding merger challenges. This is borne out by recent merger decisions.

In FTC v. Sysco, for example, the court extensively analyzed evidence relevant to the qualitative factors in Brown Shoe Co. v. United States in determining that broadline foodservice distribution was a market. Among other things, it had distinct product characteristics, distinct customers and the industry recognized the uniqueness of these services. The FTC’s economist also presented the results of an aggregate diversion analysis that showed a hypothetical monopolist over these services could profitably raise prices by a small but substantial and non-transitory amount. Rather than relying on these precise findings, the judge viewed them together with the rest of the evidence with which they were consistent. The defendant’s economist’s testimony, on the other hand, was not accepted by the court because it was contradicted by the weight of the qualitative evidence. In other words, it was the qualitative evidence that did the heavy lifting.

Similarly, in United States v. Bazaarvoice, the Antitrust Division introduced extensive evidence – including the parties’ own documents and lay witness testimony – showing that the market was limited to product rating and review (R&R) platforms, a market in which the merging firms were the two largest players. The division’s expert also presented the results of a hypothetical monopolist test on this question, but the court simply found that this “confirm[ed] what was apparent from the non-expert testimony,” i.e., that “R & R platforms in the United States for retailers and manufacturers are the relevant product and geographic markets.”

Sysco and Bazaarvoice are not unusual cases. One more example: in United States v. H & R Block Inc., the district court defined the market with reference to documentary and lay witness testimony, finding the economics testimony merely “tend[ed] to confirm” the market.

I will close by saying that this is an exciting time to be a lawyer or an economist practicing in the field of merger control. The agencies have been bringing cases across a variety of industries that have presented a range of important issues. With six years of experience under the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, the principles that are embedded in that document have been extensively debated and applied by the agencies and in some instances by the courts. Concepts like upward pricing pressure have become familiar to everyone practicing in the area. The economics profession should be rightly proud of its important role in bringing us to this place but must not rest on its laurels. There is endless work to be done to invent newer and better tools to study markets, develop consensus around the things that work and the things that don’t and figure out how to help the agencies and the courts make good decisions.

It is surprising to see the extent to which trust plays an important role in the antitrust arena, or for that matter, any legal setting, where once the validity of an economic analysis is called into question as described above, so is the ethical integrity of the analyst who produced it. Analysts would do very well to remember that one single lesson from today's example of junk science.

But perhaps the most surprising lesson to take away from today's example of junk science is how little weight the quantitative aspects of econometric analysis carries with respect to more qualitative evidence in antitrust cases. It is not just the data and the corresponding analysis that matters so much in these cases as it is the context of the full spectrum of evidence in which such data and analysis is presented. If the econometric analysis doesn't jibe with that larger qualitative picture, it will be discarded - and in the cases where it is based on junk science, as in the cherry picking example presented in the discussion above, or as in the other examples that we've presented as part of this series, rightfully so.

References

Gelfand, David. U.S. Department of Justice. "Deputy Assistant Attorney General David Gelfand Delivers Remarks at the Bates White Antitrust Conference". Washington, D.C., United States, Monday, June 6, 2016. [PDF Document]. Updated 29 September 2016. Excerpted with permission.

Lysy, Chris. Cherry Picking Data. Fresh Spectrum. [Online Illustration]. Accessed 6 October 2016. Republished with permission.