A Credit Default Swap (CDS) is a special kind of insurance policy that can be purchased by individuals or institutions that invest in debt securities to protect themselves from losses if the issuer of the debt chooses to default on their obligations.

The annual cost of this special kind of insurance policy is called the "spread". As with any kind of insurance, the cost of a CDS spread for a debt issuer who has a high probability of defaulting on their debt payments is higher than it is for a debt issuer who has a low probability of not making good in paying off their debts.

The chart below shows the relationship between CDS spreads and the cumulative probability that the debt issuer will default on their debt payments during the next five years for a number of sovereign governments:

Compared to a debt issuer that has a low risk of default, a debt issuer with a higher risk of defaulting on their debt payments will also pay more to the individuals or institutions that loan them money. These higher payments are reflected in the interest rates, or yields, they agree to pay for the debt securities they issue.

As it happens, there's a very direct relationship between the interest rate a debt issuer pays and the value of a CDS spread on the debt they issue. Here is a chart showing the yields of government-issued 10-Year debt securities against the CDS spreads on those debt securities for a number of sovereign governments:

In general, each 100 point increase in the risk of default as measured by CDS spreads corresponds to a 1% increase in the interest rates the debt issuers must pay to the individuals and institutions that loan them money.

We should note that there are other factors that can influence interest rates without affecting the risk of a debt default, such as inflation. We can recognize the influence of inflation however in the chart above by seeing how far above or below the individual data points fall with respect to the general trend line mapped out between interest rates and CDS spreads.

Meanwhile, the general trend line gives us the means by which we can determine how much a change in CDS spreads can effectively change a country's interest rates. And a change in a nation's interest rates can give us a good idea of how much its GDP may be affected by a change in the risk that it will default on its debt.

Here, for the case of the United States, we can apply a rule of thumb provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. The Fed estimated that a 1% change in the yield, or interest paid, paid out for a 10-Year U.S. Treasury corresponds to a 2.65% change in the growth rate of the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the opposite direction.

So a 1% drop in the U.S. 10-Year Treasury will act to increase U.S. GDP growth rate by 2.65%, because a lower interest rate lowers the costs of things like mortgages and the cost of borrowing to support business expansion, while a 1% increase in the U.S. 10-Year Treasury will act to decrease the growth rate of U.S. GDP by 2.65%, making mortgages and business loans more costly.

Using this information, we can now work out how much an increase in the risk of default for the United States over the last several years is hurting U.S. GDP.

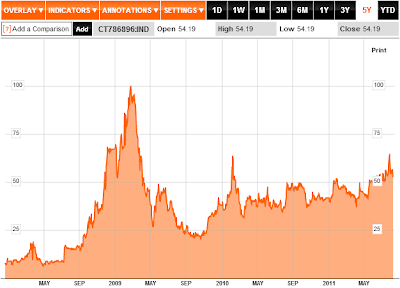

The next chart shows how the U.S. 10-Year Treasury's CDS spreads have changed since late 2007, when the risk of a U.S. default on its debt was minimal, to the levels recorded in the days immediately after the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011, following the U.S. national debt limit debate in the summer of 2011.

What we see is that compared to the pre-financial crisis level of CDS spreads that ranged between 6 and 10, when the U.S. was seen to have almost no risk of defaulting on its debt payments, today's CDS spreads are almost 50 points higher on average, ranging between values of 52 and 56 since the Budget Control Act passed into law.

That 50 point difference between today's higher risk of default vs the almost zero risk of default before 2008 means that the yield on today's 10-Year U.S. Treasury is about 0.5% higher than it might otherwise be, if not for the increase in the risk that the U.S. might default on some of its debt payments.

Applying the Fed's rule of thumb for determining the impact of a change in the 10-Year Treasury's interest rate, that 0.5% increase in the yield for investors is lowering the U.S. GDP growth rate of about 1.2-1.3% in the first half of 2011.

If we go back to 2010, we find that the average increase in the CDS spreads for that year were about 40 points above the almost-zero risk of default level. We therefore find that GDP growth in that year was effectively reduced by 1.1% below what it would otherwise have been.

Our tool below will estimate the effective impact on GDP for the change in CDS spreads you enter. The default value for the Current CDS Spread is that recorded for 10 August 2011:

The causal factor for the increase in the U.S. government's risk of a default on the debt it has issued is the rapid increase in federal government spending that has occurred since 2007 and most significantly since 2008. The following chart shows the projected track of U.S. federal government outlays that President Obama intended to spend prior to the passage of the Budget Control Act of 2011:

The increase in federal government spending shown in this chart, both realized and projected, is what has most contributed to the U.S. government's national debt crisis. The growth of the spending has been so extreme that it has increased the risk that the U.S. government might default on its debt payments, which in turn has been negatively affecting the growth rate of the nation's GDP since 2007.

Now, here's the kicker. Because GDP growth is being negatively affected by the increase in the likelihood that the U.S. might default on its debt payments, U.S. tax revenues have likewise been depressed below what they might otherwise have been. By hurting GDP growth, the government's spending is also hurting its tax collections.

To be able to keep spending at President Obama's desired levels, the U.S. government must borrow even more to make up for the resulting shortfall in tax collections, which then makes the underlying problem, the risk the U.S. government might default, even worse as CDS spreads get pushed up, refueling the cycle.

There's a special name for that situation. It's called a "death spiral". And while the Budget Control Act of 2011 helped lessen the U.S. government's financial rate of descent, it still has not resumed a healthy fiscal trajectory.

Labels: national debt, tool

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.