Are you a smartphone zombie? One of those people who constantly walks around while absorbed by whatever you have displayed on your smartphone screen? The kind who often accidentally runs into things or people because you're so engrossed you don't notice obstacles in your path?

This three minute video from National Geographic describes the havoc that can result from the visual impairments shared by smartphone zombies:

Yanko Design's Minwook Paeng is an industrial designer who has developed a unique solution for smartphone zombies, who he groups as a new species, Phono Sapiens. He's developed (or "evolved") a design for a third eye, a wearable sensor that opens when your head is angled down to look at your smartphone instead of ahead at where you are going. He combines it with a proximity detector that alerts you if you're about to walk into an obstacle. The model in the following very short video demonstrates it in action:

As best as we can tell, there's no patent for it (yet), nor is there anything quite like it available on the market. The closest device we could find is a portable collision warning device for the blind and visually-impaired, which seems to be in the research and prototype phase.

Recently published research indicates these devices can lead to fewer collisions and improved mobility for the visually-impaired, which suggests a real world application is awaiting the refinement of Paeng's "third eye" concept.

From the Inventions in Everything Archives

Labels: technology

Long streaks and especially long losing streaks in the S&P 500 have become much less common during the past 20 years.

That change has come however as stock prices themselves have become more volatile. The following chart visualizes the daily percentage change from the previous days close for the S&P 500 from 3 January 1950 through 30 June 2021.

In this chart, we see that large daily percentage changes have become more common in recent decades. To simplify the visualization of that change, we're calculated the standard deviation of the daily percentage change in the S&P 500 by decade, presented in the next chart, where we find the typical volatility among the U.S. stock market's largest stocks by market capitalization has increased.

The final bar, for the 2020's, differs from the others in that it doesn't cover a full decade's worth of stock price changes. It covers the typical volatility observed to date in the year and a half from 2 January 2020 through 30 June 2021.

Still, it's a big jump over the preceding decade long periods, where we also see that the S&P 500 index in the decades of the 2000s have been considerably more volatile than the five decades that preceded them. The increase in the typical standard deviation indicates by decade bigger daily changes in stock prices have become more common in the 2000s.

That change offers a potential explanation for why losing streaks have become less common over the same period. Since the stock price volatility as measured by standard deviation has become larger than in previous decades, indicating larger daily changes when volatility breaks out, stock prices more quickly reach thresholds where investors buy the dips, which translates into shorter losing streaks.

Exit question: how profitable is buying big dips as a trading strategy?

References

Yahoo! Finance. S&P 500 Historical Data. [Online Database]. Accessed 2 July 2021.

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: data visualization, SP 500, volatility

The reports of how COVID-19 changed U.S. life expectancy are grim.

The pandemic crushed life expectancy in the United States last year by 1.5 years, the largest drop since World War II, according to new Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data released Wednesday. For Black and Hispanic people, their life expectancy declined by three years.

U.S. life expectancy declined from 78.8 years in 2019 to 77.3 years in 2020. The pandemic was responsible for close to 74 percent of that overall decline, though increased fatal drug overdoses and homicides also contributed.

“I myself had never seen a change this big except in the history books,” Elizabeth Arias, a demographer at the CDC and lead author of the new report, told The Wall Street Journal.

The figures for just COVID-19's impact on U.S. life expectancy are roughly in line with the CDC's preliminary estimates from February 2021, which was based on the then-available data through the first half of 2020.

Unfortunately, the CDC's estimates are rather misleading. Dr. Peter Bach, the director of the Center for Health Policy and Outcomes at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, ran some back of the envelope calculations after the CDC released its preliminary estimates and came up with very different results.

The CDC reported that life expectancy in the U.S. declined by one year in 2020. People understood this to mean that Covid-19 had shaved off a year from how long each of us will live on average. That is, after all, how people tend to think of life expectancy. The New York Times characterized the report as “the first full picture of the pandemic’s effect on American expected life spans.”

But wait. Analysts estimate that, on average, a death from Covid-19 robs its victim of around 12 years of life. Approximately 400,000 Americans died Covid-19 in 2020, meaning about 4.8 million years of life collectively vanished. Spread that ghastly number across the U.S. population of 330 million and it comes out to 0.014 years of life lost per person. That’s 5.3 days. There were other excess deaths in 2020, so maybe the answer is seven days lost per person.

No matter how you look at it, the result is a far cry from what the CDC announced.

We built the following tool to do Bach's math, which checks out. You're welcome to update the figures with improved data or to replace them with other countries' data if you want to see the impact elsewhere in the world. If you're accessing this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click through to our site to access a working version of the tool.

So why is the CDC's estimate of the change in life expectancy estimate so different? As Bach explains, it is not because of either the data or the math, but rather, it is because of the CDC's assumptions in doing their math:

It’s not that the agency made a math mistake. I checked the calculations myself, and even went over them with one of the CDC analysts. The error was more problematic in my view: The CDC relied on an assumption it had to know was wrong.

The CDC’s life expectancy calculations are, in fact, life expectancy projections (the technical term for the measure is period life expectancy). The calculation is based on a crucial assumption: that for the year you are studying (2019 compared to 2020 in this case) the risk of death, in every age group, will stay as it was in that year for everyone born during it.

So to project the life expectancy of people born in 2020, the CDC assumed that newborns will face the risk of dying that newborns did in 2020. Then when they turn 1, they face the risk of dying that 1-year-olds did in 2020. Then on to them being 2 years old, and so on.

Locking people into 2020 for their entire life spans, from birth to death, may sound like the plot of a dystopian reboot of “Groundhog Day.” But that’s the calculation. The results: The CDC’s report boils down to a finding that bears no relation to any realistic scenario. Running the 2020 gauntlet for an entire life results in living one year less on average than running that same gauntlet in 2019.

Don’t blame the method. It’s a standard one that over time has been a highly useful way of understanding how our efforts in public health have succeeded or fallen short. Because it is a projection, it can (and should) serve as an early warning of how people in our society will do in the future if we do nothing different from today.

But in this case, the CDC should assume, as do we all, that Covid-19 will cause an increase in mortality for only a brief period relative to the span of a normal lifetime. If you assume the Covid-19 risk of 2020 carries forward unabated, you will overstate the life expectancy declines it causes.

In effect, the CDC's assumption projects the impact of COVID-19 in a world in which none of the Operation Warp Speed vaccines exist seeing as they only began rolling out in large numbers in the latter half of December 2020.

When the CDC repeats its life expectancy exercise next year, its estimates of the change in life expectancy should reflect the first year impact of the new COVID-19 vaccines, which will make for an interesting side by side comparison. Especially when comparisons of pre-vaccine case and death rates with post-vaccine data already look like the New Stateman's chart for the United Kingdom:

Labels: coronavirus, health, risk, tool

A combination of upward price adjustments in the average prices of new homes sold in the U.S. in recent months with smaller than expected downward revisions in the number of sales has produced a surprising outcome for the market capitalization of new homes in the U.S. In June 2021, the trailing twelve month average for the U.S. new homes market cap has risen for the first time since it peaked in December 2020.

The initial estimate for the market capitalization of new homes sold in the U.S. rose to $30.2 billion in June 2021, up from a trough of $29.6 billion in the preceding month. The market cap for new homes sold in the U.S. last peaked at $31.15 billion in December 2021.

The surprising rebound comes after June 2021's sales volume for new homes recorded their lowest seasonally adjusted annualized rate since April 2020, which marked the bottom of the coronavirus pandemic recession. Thr result is based on initial data for June 2021's sales figures that will be revised at least two more times before being finalized in the next several months.

Looking at regional data, the biggest drop in the initial number of seasonally-adjusted annualized reported sales occurred in the U.S. Census Bureau's northeast region, which fell by 27% from May 2020. The number of sales also fell in the South, but by a much smaller percentage. Revisions for these regions will be something to pay attention to in upcoming months to see if the initial estimate of June 2020's market cap is a blip or the end of a microrecession for the industry.

References

U.S. Census Bureau. New Residential Sales Historical Data. Houses Sold. [Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 27 July 2021.

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers - (CPI-U), U.S. City Average, All Items, 1982-84=100[Online Application]. Accessed 13 July 2021.

Labels: real estate

The S&P 500 (Index: SPX) breached the 4,400 level before closing the trading week ending 23 July 2021 at 4,411.70 - a new record high for the index.

As you can see in the following chart, that's right in line with where the dividend futures-based model says it should be when investors are keeping their focus on 2022-Q1 in setting current day stock prices.

The past week didn't have much news coming out from the Fed's minions, who are currently incommunicado in news blackout period ahead of its 27-28 July 2021 meetings. The news blackout will lift on Wednesday, 28 July 2021, after which investors can expect the Fed's minions to shift into overdrive and deliver a torrent of news.

Meanwhile, there was news, but a lot less of it during the week that was. Here is our summary of its market-moving news headlines:

- Monday, 19 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- U.S. homebuilder confidence falls to 11-month low in July

- Oil piles on losses following OPEC+ deal to boost supply, rising COVID cases

- U.S. recession ended in April 2020, making it shortest on record

- Biden says inflation temporary; Fed should do what it deems necessary for recovery

- Central banks talking about ending pandemic stimulus:

- What might the Bank of England do to wean the UK economy off stimulus?

- Inflation and the Bank of England: what its rate-setters are saying

- BoE's Haskel sees no need to curb stimulus in foreseeable future

- South Korea poised to kick-start Asia's monetary tightening

- Strategy Review, tick, next? Five questions for the ECB

- Wall Street ends sharply lower as Delta variant sparks new lockdown fears

- Tuesday, 20 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- U.S. housing starts rise, building permits fall to eight-month low

- U.S. states ending federal unemployment benefit saw no clear job gains

- Bigger inflation developing all over:

- Canadian home prices climb in June at record annual pace -Teranet

- U.S. housing starts rise, building permits fall to eight-month low

- Bigger stimulus developing in Australia:

- Global trade, supply chain problems growing:

- Taiwan June export orders surge again, outlook bullish

- Electrolux braces for more disruptions from global supply chain squeeze

- Wall Street bounces back on renewed economic optimism

- Wednesday, 21 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- COVID recovery in US, China/COVID recession in Australia:

- Japan's exports jump on solid U.S., China demand

- June slump in Australia's retail sales clouds third-quarter growth outlook

- Wall Street ends higher, powered by strong earnings, economic cheer

- Thursday, 22 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- U.S. housing market floats back to earth

- U.S. weekly jobless claims increase to two-month high; trend still low

- COVID controlling Australia's economy:

- Bigger inflation on the minds of the BOE's minions:

- ECB minions on board with bigger inflation in Eurozone; fear another pandemic wave:

- ECB promises even longer support for euro zone economy

- ECB pledges record low rates to reach 2% inflation

- TEXT-Statement from the ECB following policy meeting

- TEXT-Lagarde's statement after ECB policy meeting

- Lagarde comments at ECB press conference

- Lagarde's communication revolution falls short of hype: analysts

- Stocks near record high after ECB talks of 'forceful' support

- ECB sees some risks to outlook from fresh pandemic wave

- Wall Street closes up after choppy trading due to higher jobless claims

- Friday, 23 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Bigger inflation developing all over:

- Rapid German recovery triggering inflation bottlenecks - PMI

- Russia raises key rate to 6.5% in sharpest move since 2014

- ECB minions expect higher growth and inflation, "totally" on board with more stimulus, but don't expect to know how much anytime soon:

- ECB survey sees higher growth, inflation in next 2 years

- ECB policymakers don't expect to decide on bond buys in September -sources

- U.S. stock markets hit new highs, Treasury yields up as choppy week ends

If you’re looking for market news about a specific company or the history of its stock prices, Yahoo! Finance is a very useful resource, particularly for the latter, where we’ve linked to its price history for the S&P 500.

Suppose for a minute that you just wagered 25 cents on the outcome of a coin flip with a friend. The coin flip happens, you call "heads" while it's in the air, but after it falls, it comes up "tails". You've lost.

Your friend offers you the chance to go again. You take it, but you double the size of your bet to 50 cents. The coin is flipped and you call "tails", but it comes up "heads" and you lose again. Now, you're down 75 cents. Your friend offers you another chance to play.

Once again, you take it. But once again, you double the size of your bet, raising it to one dollar (or 100 cents, if you prefer). This time, the outcome of the coin toss matches your call, and you win. You've gone from 75 cents in hole to a net gain of 25 cents compared to when you started playing.

You may not realize it, but you've been using the martingale system (or strategy) in choosing the size of your bets. The strategy was first put forward by French mathematician Paul Lévy, who realized that one winning bet was all that was needed to turn around and fully reverse the outcome of a series of losing bets. Of course, the catch is that you have to have sufficient resources to weather the losses while you're racking up losing bets and realistic odds of eventually winning your wager to make it work for you, but if you want to learn more about the mathematical insight behind it, check out the following 19 minute Numberphile video featuring Tom Crawford.

If you're ready to head to the casino after seeing the video, you can rest assured you will not see any games where you have a 50% chance of winning or losing. There are some games that come close to those odds, but the potential rewards will be less.

With some modifications, you could apply the system to investing, but you'll find that approach has many of the same limitations:

Drawbacks of the Martingale Strategy

- The amount spent on trading can reach huge proportions after just a few transactions.

- If the trader runs out of funds and exits the trade while using the strategy, the losses faced can be disastrous.

- There is a chance that the stocks stop trading at some point in time.

- The risk-to-reward ratio of the Martingale Strategy is not reasonable. While using the strategy, higher amounts are spent with every loss until a win, and the final profit is only equal to the initial bet size.

- The strategy ignores transaction costs associated with every trade.

- There are limits placed by exchanges on trade size. Therefore, a trader does not receive an infinite number of chances to double a bet.

Don't forget that time is one of the transaction costs you pay. So are opportunity costs, because you may have other, better things to do with your stake that you are passing up by trying to come out just slightly ahead in continuing to play the same game you started losing.

As of 2019, roughly one third of polled Americans favor abolishing the penny.

That's still a minority, since over half of Americans responding to that poll favored keeping the penny circulating in the U.S. economy. But with inflation rising and the penny falling in value, the economics for keeping the penny in use are changing. From that perspective alone, it might soon be worth revisiting whether the U.S. Mint should continue stamping out the millions of copper-plated zinc discs it does each year.

That would follow the example of Canada. We learned a lot of economic arguments in favor of abolishing the penny from that country's "Godfather of the Ban-the-Penny Movement".

But we hadn't encountered an environmental argument against the lowest value U.S. coin in circulation until the American Council on Science and Health's Josh Bloom did some back-of-the-envelope math to quantify some of that impact.

Here's a portion of that discussion:

Pennies are not only a nuisance (stores hate them), but they are also an environmentally harmful nuisance. Here are a few facts that support this.

- The melt value of a zinc penny is one-half of a cent.

- Even so, according to the US Mint, it costs about 2.4 cents to make one penny.

- In 2013 alone, this cost taxpayers $105 million.

- Since 1982, 327 billion pennies have been minted.

- A zinc penny weighs 2.5 g.

- Doing the math, 327 billion pennies weigh 1.8 billion pounds

- Tractor-trailer trucks can transport 80,000 pounds.

- Given these figures, it required 22,500 full trucks to transport all the pennies that were minted since 1982.

- A full tractor-trailer truck gets about 5 mpg.

- Assuming that your average penny must travel 1,000 miles from the mint to wherever it is going (pure guess), it has taken 4.5 million gallons of fuel just to transport all the pennies that have been minted since 1982.

- One gallon of diesel fuel produces 23.8 pounds of carbon dioxide when burned.

- So, by simply hauling around all the stupid useless pennies since 1982, 107 million pounds of carbon dioxide has been emitted, plus who knows how much diesel pollution.

- A whole bunch of zinc is being mined for no good reason. The mining itself causes more pollution.

- About two-thirds of pennies don't even circulate. They are either thrown out or sitting around in jars.

- Other countries have dropped the penny and started rounding off to the nearest five cents. It worked out just fine.

- Some of this math may be correct.

And, these (very) rough calculations do not include the energy needed to mine the zinc ore, transport it to a smelter, purify the ore, transport the purified zinc to the mint, and then make it into pennies.

And that doesn't consider that most the world's zinc, including that used to make U.S. pennies since 1982, is mined in China before being shipped overseas, which also adds to the coin's carbon footprint.

We think the changing economics of pennies will have more impact on whether it makes sense to stop minting them than the environmental case. Exit question: how many people have already begun hoarding the copper pennies minted in 1982 and earlier the way people harvested silver coins out of general circulation after they stopped being minted in 1964?

References

Bloom, Josh. If Cash Is No Longer King What Does That Make Stupid Pennies? American Council on Science and Health. [Online Article]. 16 July 2021.

U.S. Mint. H.I.P. Pocket Change Kids Site: Penny. [Online article]. 2021.

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: environment

In 2010, U.S. compensation and data software firm Payscale identified the 10 lowest paying college degrees for those starting their first jobs in their fields after graduation. We wondered how on the mark that list was, so we tapped Payscale's 2020 data for starting wages by college major to see if things got relatively better or worse for today's graduates in those fields.

The results are shown in the following chart. The original 2010 data is shown in blue and the newer 2020 data is shown in green. In between, in orange, we've adjusted the 2010 starting salary data for inflation to be in terms of 2020 U.S. dollars to make those older salaries directly comparable to the actual starting pay for graduates in the listed fields in 2020.

After adjusting for inflation, we see only two degrees where the actual starting pay for graduates in 2020 is ahead of 2010's inflation-adjusted level: Athletic Training and Elementary Education. Horticulture comes close to breaking even, so to speak, and the remaining fields would appear to have become even less rewarding.

Of these less rewarding degrees, Culinary Arts presents the biggest gap between 2010's inflation adjusted pay and 2020's actual starting pay, followed by Special Eduation and Paralegal Studies.

In 2010, Payscale also indicated what an individual holding these degrees could expect to make at a mid-career point, some 10 or more years after graduation. Since it's 10 years later, we thought it would be especially interesting to see how 2020's actual mid-career pay compares with 2010's inflation-adjusted mid-career pay. Our results are shown in the next chart:

Once again, the fields of Culinary Arts and Athletic Training come out the furthest ahead after accounting for inflation, but Theology graduates also gained more income than would have been expected based on 2010's inflation-adjusted pay.

Most the other fields saw their 2010 graduates making something within a several percent of their 2010 peers' inflation adjusted pay, with one big exception, which looks like it is in error.

According to Payscale's 2020 survey data, individuals holding degrees in Special Education with 10 or more years of experience saw the average mid-career pay in their field collapse. At $54,500, it is just $700 higher than 2010's non-inflation adjusted pay, some $9,800 below what adjusting the mid-career income for 2010 would predict.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates the median pay for Special Education teachers was $61,420 per year in 2019, which is more in line with Payscale's 2010 inflation-adjusted mid-career income figure.

We sampled other income data for other fields, which appears to be in line with Payscale's surveyed reults, so the 2020 mid-career pay figure for Special Education degree holders appears to be an outlier.

Overall, it appears most of 2010's lowest paying degrees for college graduates turned out to be as bad for pay 10 years later as 2010's data suggested they would be.

Labels: education, income, jobs

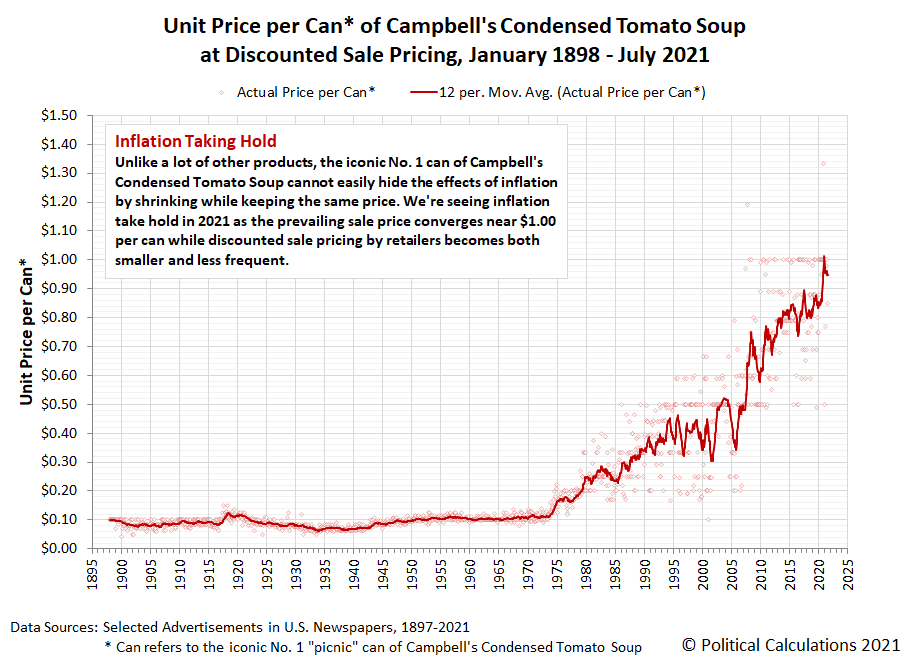

Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup has long been our favorite way to visualize the effects of inflation over time in the U.S. economy. That's because the product is defined by its iconic packaging, a No. 1 size steel can that contains the same amount of condensed tomato soup as it did when the product was first introduced to the public in the late 1800s.

For the latest in our coverage of Campbell's Tomato Soup prices, follow this link!

This relative stability in packaging however means Campbell Soup (NYSE: CPB) cannot hide the price increases it passes along to its customers through shrinkflation, which many other food producers exploit by keeping the same prices on their goods, but diminishing the amount of goods within them. When inflation drives up the costs of what they have to pay to make and transport their goods to consumers, Campbell's must increase their prices to compensate.

That's what's happening now. Campbell Soup has confirmed it is increasing prices across its product lines:

Get ready to add a few dollars to your monthly canned soup budget, because thanks to rising supply chain costs, Campbell’s is planning to raise its prices. On Wednesday, Campbell’s announced its last-quarter earnings were weaker than the company had expected. Compared to the same time period last year, profits had fallen 5% to $160 million.

“Our results were impacted by a rising inflationary environment, short-term increases in supply chain costs, and some executional pressures,” said CEO Mark Clouse....

Clouse assured investors that the company is taking steps to recover from the slump, including a new pricing strategy, which will roll out over the current quarter (which ends in early August). Across the company portfolio Campbell’s net sales decreased 14% over the last quarter, so expect this pricing strategy to affect more than just canned soup—Swanson broth, Pop Secret popcorn, Cape Cod chips, Pace salsa, Snyder’s of Hanover pretzels, V8 juice, Prego tomato sauce, SpaghettiOs, and Pepperidge Farm are all owned by Campbell’s.

Whether or not you, personally, will be paying more for these products is yet to be seen. Though retailers will be paying more for Campbell’s products, it’s ultimately up to them whether or not to absorb the higher costs, or pass them onto consumers.

The markup between wholesale and retail prices give retailers some flexibility in how they might choose to pass their increased costs along to consumers. And that is where we can show how that works, because we've tracked the prices consumers have paid for Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup since the product rolled out onto grocery store shelves in the late 1800s.

For products like Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup, retailers pass along their cost increases to consumers by offering fewer and smaller discounts. This marketing strategy lets them hold their shelf prices relatively stable, but only until inflationary pressures rise enough to force retailers to increase their shelf price. Once they do, their higher markups allow them to regain the ability to offer larger discounts.

You can see that dynamic playing out in this chart as prices have periodically stepped upward in 5 to 10 cent intervals since the U.S. government ended its failed attempt to stop inflation through price controls in 1974. As prices have risen, deep discounting becomes much less common and eventually the low prices consumers were once able to pay becomes a thing of the past.

In 2021, the price of Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup is converging near a shelf price of $1.00 per 10.75 ounce can. In July 2021, the trailing twelve month average discounted sale price is $0.95 per can, which has fallen from a seasonal peak of $0.99 per can in December 2020 thanks largely to some unique pandemic-driven supply and demand dynamics. We think we'll start seeing higher retail shelf prices in the very near future to confirm the permanence of 2021's inflation.

Labels: inflation, personal finance, soup

The S&P 500 (Index: SPX) started the trading week strong, reaching a record high close of 4,384.63 on Monday, 12 July 2021 before losing steam and retreating through much of the rest of the week. The index closed the week at 4,327.16.

That's generally consistent with the dividend futures-based model's projections for investors focusing their attention on 2022-Q1 in setting current day stock prices.

While the model looks forward to a sideways to slowing rising run over the next several weeks if investors keep their focus on 2022-Q1, it also indicates the risk of a 5% decline should investors have reason to shift their attention back to the current quarter of 2021-Q3.

Whether that happens will depend much on what happens with the outlook for inflation in the U.S. economy, which continues to play an outsized role in the news influencing investors' expectations.

- Monday, 12 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- U.S. consumers' short-term inflation outlook jumps, NY Fed survey shows

- Oil prices slip as economic fears offset tightening crude supplies

- Bigger inflation developing all over:

- Bigger trouble developing in Australia, Thailand:

- Australian banks must have a plan to deal with negative interest rates by 2022 - APRA

- Thai economy may miss forecasts as COVID-19 cases spike - central bank

- ECB minions plan to figure out what they're doing soon:

- ECB to discuss new guidance after inflation target tweak -Vice President

- ECB to chart new policy path next week

- Tesla lifts S&P 500 to record highs

- Tuesday, 13 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- U.S. consumer prices post largest gain in 13 years; inflation has likely peaked

- U.S. fed funds, eurodollar futures raise rate hike bets after CPI data

- Conagra tamps down full-year profit expectations as input costs soar

- Oil rises nearly 2% as investors size up tight market

- Fed minion talks about tapering stimulus bond buys sooner rather than later with hot inflation, investors want to hear from Powell:

- Fed's Bullard says time is right to reduce central bank's bond buying - WSJ

- Analysis: Investors pivot to Powell after more hot U.S. inflation data

- ECB minions want to keep stimulus going, need to figure out what they mean by tolerance for higher inflation:

- 'Persistent' ECB won't tighten too early, Lagarde says

- ECB's new guidance must show there is leeway on inflation -Centeno

- S&P 500 and Nasdaq end down after hitting record highs

- Wednesday, 14 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Biggest U.S. banks smash profit estimates as economy revives

- Port of Los Angles sets new volume record for June

- Fed minion looking like will keep job, wants to keep stimulus bond buy pump going, thinks inflation will go away:

- Seven months and ticking, the case for keeping Powell as Fed chair builds

- Job gains strong, prices rising as U.S. recovery continues -Fed Beige Book

- Fed's Powell tamps down taper talk but feels inflation heat on the Hill

- ECB minions want to keep stimulus going longer:

- S&P 500 ends higher after Powell lulls market

- Thursday, 15 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- NY Fed Empire State business conditions index surges to record 43.0 in July vs 17.4 in June

- Amazing what finally lifting a lockdown can do….

- U.S. import prices rise solidly in June

- U.S. weekly jobless claims at 16-month low; shortages hamper manufacturing

- Fed minion gets grilled about inflation:

- Bigger inflation developing all over:

- Bigger trouble developing in and around China:

- ECB minions want to keep stimulus going longer:

- Nasdaq ends lower as investors sell Big Tech

- Friday, 16 July 2021

- Signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- BofA lowers U.S. 2021 GDP forecast to 6.5% from 7.0%

- Cash-flush Americans lift U.S. retail sales; shortages depress auto purchases

- U.S. consumer sentiment drops in early July on inflation fears

- Fed minion likely to keep job:

- ECB minions to talk about future of stimulus policies, have less inflation than expected:

- ECB policymakers set for showdown on policy path

- Euro zone inflation easing confirmed, trade surplus dips

- Wall Street ends down as Delta variant drives fears

Looking for additional markets and economics news? Check out Abnormal Returns, in which Tadas Viskanta provides a daily roundup of links to interesting news and analysis.

With record hot temperatures this summer, the IIE team has been inspired to seek out inventions that promise to deliver the one thing many on the team crave this time of year: a cool, refreshing beverage!

Better still, what we want is something that will help keep our canned or bottled beverage cool enough, long enough so we can enjoy consuming its contents at a leisurely pace. Because when it is as hot as it has been, the last thing we want to do is expend more energy to consume our drink of choice at a rushed pace before it gets too warm to be worth consuming.

That brings us to today's featured invention, for which inventors Mason McMullin, Robert Bell, and Mark See were issued U.S. Patent 6,637,447 on 28 October 2003. Here's Figure 1 from the patent, which illustrates not just what the invention is, but also acts as an instruction manual for how to install it in the field, so to speak.

In case it is not clear from the figure, here is the description of the invention from the patent's abstract:

The present invention provides a small umbrella ("Beerbrella") which may be removably attached to a beverage container in order to shade the beverage container from the direct rays of the sun. The apparatus comprises a small umbrella approximately five to seven inches in diameter, although other appropriate sizes may be used within the spirit and scope of the present invention. Suitable advertising and/or logos may be applied to the umbrella surface for promotional purposes. The umbrella may be attached to the beverage container by any one of a number of means, including clip, strap, cup, foam insulator, or as a coaster or the like. The umbrella shaft may be provided with a pivot to allow the umbrella to be suitably angled to shield the sun or for aesthetic purposes. In one embodiment, a pivot joint and counterweight may be provided to allow the umbrella to pivot out of the way when the user drinks from the container.

That latter capability is key, because otherwise, one would have to expend excess energy to constant detach and reattach the invention while drinking.

At this point, you might think an invention like the Beerbrella is somewhat redundant. After all, haven't there been any number of inventions whose purpose is to keep a can or bottle of beer colder for longer after being removed from a refrigerated environment through the miracle of insulation?

Alas not, according to the Beerbrella's inventors, who describe where previous inventions have fallen short by providing incomplete coverage.

For example, the popular insulated beverage sleeve known as a "coozie" may be provided, manufactured of soft expanded polyurethane foam. These beverage sleeves are typically provided with an applied graphic advertising a beverage brand or the name of the company giving away the device as a promotion. A can, glass, or bottle may be inserted into the sleeve. The sleeve acts as an insulator to prevent ambient heat as well as heat from the user's hands, from warming the beverage.

Similar devices are known for use specifically with bottles beverages. In this variation, a tailored expanded polyurethane jacket may be provided, replete with zipper, to encapsulate substantially all of a bottle.

Various devices are known for supporting beverages, such as coasters and the like as well as beverage stands, trays, and supports. One example is illustrated in Foley et al., U.S. Pat. No. 5,823,496, issued Oct. 20, 1998 and incorporated herein by reference. Foley provides an outdoor stand with a stake or pole which may be inserted into the ground to support a beverage container.

Similia, U.S. Pat. No. 4,638,645, issued Jan. 27, 1987 and incorporated herein by reference, discloses a beverage container cooler for receiving a single beverage container (e.g., can) and providing a location for ice or the like to cool the beverage.

One problem with these Prior Art devices is that although they do provide insulation for beverages, they do not shield the beverage from the direct rays of the sun. A beverage left out in the sun, even if insulated or cooled with ice, quickly warms due to the effect of the intense infrared radiation from the sun, particularly on hot, sunny summer days.

Thus, it remains a requirement in the art to provide a means for shielding a beverage from direct sunlight.

They convinced a U.S. patent examiner with this irrefutable logic, who proceeded to award them with a U.S. patent for their invention of the Beerbrella.

Unfortunately, we could find no examples of where the Beerbrella could be purchased today, over 17 years after its patent was issued. It would appear consumers have settled on the alternative strategy of simply drinking their beverages slightly faster whenever their drinks are at risk of becoming too warm for optimal consumption when exposed to direct sunlight.

From the Inventions in Everything Archives

The IIE team has previously covered the following related inventions:

Labels: food, technology

It has been nearly two months since we focused on Arizona's experience during the coronavirus pandemic. When we last checked, it appeared Arizona's level of COVID cases following the surge of uncontrolled immigrant crossings into the state was stabilizing.

That pattern held through the end of May 2021. However, beginning in the first week of June 2021, Arizona has experienced a slow upward trend in cases. That new trend can be seen in the following chart tracking the 7-day moving averages of the state's COVID cases and new hospital admissions. Presented in logarithmic scale, the figures for each data series has been aligned with respect to the approximate date of initial exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus variants infecting those who have tested positive for COVID-19.

At this time, the data for COVID deaths is as yet too incomplete to confirm the change in trend across all three data series.

The change in trend appears to roughly coincide with the Phoenix Suns' first trip to the NBA playoffs in more than a decade, which prompted large crowd gatherings and celebrations after the team beat the Los Angeles Lakers in the first round of the playoffs in the first week of June 2021. The team has continued its success, beating both the Denver Nuggets and the Los Angeles Clippers, and is now playing the Milwaukee Bucks for the championship in the NBA finals.

The situation parallels the change in trend we observed in California after the Los Angeles Dodgers won the World Series. The main difference is that Arizona's current upward trend is rising at a much slower rate. We think that difference is attributable to the Operation Warp Speed coronavirus vaccines, which have been successfully deployed to half the state's population, especially the state's senior population, which has reduced the incidence of COVID-related hospitalizations and deaths.

The state is also seeing an uptrend in COVID ICU cases that has really picked up in late June 2021.

The timing of the increase in COVID ICU bed usage is delayed about two weeks behind what we would expect for a major change in the rate of incidence beginning in the first week of June 2021. We think this delay may be similar to what Arizona experienced following the Black Lives Matter protests and riots in late May and early June 2020 because of the age demographics of the participants. Then as now, younger individuals less likely to require hospitalization were infected in relatively larger numbers, which then spread to the older individuals they came in contact with following the event. The older individuals were the ones who drove up hospital admissions and ICU bed usage after they became sick, roughly two weeks afterward.

Exit question: Will any enterprising attorneys make the connection and hold the NBA accountable? They don't seem to have figured out the BLM protest connection in Arizona's May-June 2020 surge in COVID cases....

Previously on Political Calculations

Here is our previous coverage of Arizona's experience with the coronavirus pandemic, presented in reverse chronological order.

- Increase in Arizona COVID Cases from Border Migration Crisis Stabilizing

- COVID-19 and the 2021 Border Migration Crisis in Arizona

- Improving COVID Trends Bottom and Flatline in Arizona

- Surge of Migrants, Lifting of Business Capacity Limits Change Arizona COVID Trends

- COVID-19 in Retreat in Arizona With Vaccines Gaining Traction

- The Ebb and Flow of COVID-19 in Arizona's ICUs

- Arizona's Plunging COVID-19 Caseloads and the Vaccines

- Arizona Enters Downward Trend for COVID-19 After Second Peak

- Arizona Passes Second COVID-19 Peak

- A Tale of Two States and the Coronavirus

- COVID-19 Questions, Answers, and Lessons Learned from Arizona

- The Deadly Intersection of Anti-Police Protests and COVID-19

- 2020 Campaign Events Drive Surge in Arizona COVID Cases

- Arizona Arrives at Critical Junction for Coronavirus Cases

- Arizona To Soon Reach A Critical Junction For COVID-19

- Getting More Than Care from Arizona's COVID ICU Beds

- Arizona's Decentralized Approach to Beating COVID

- Going Back to School with COVID-19

- Arizona Turns Second Corner Toward Crushing Coronavirus

- Arizona's Coronavirus Crest in Rear View Mirror

- The Coronavirus Turns a Corner in Arizona

- A Delayed First Wave Crests in the U.S. and a Second COVID-19 Wave Arrives

- The Coronavirus in Arizona

- A Closer Look at COVID-19 Deaths in Arizona

- The New Epicenter of COVID-19 in the U.S.

- How Long Does a Serious COVID Infection Typically Last?

- How Deadly is the COVID-19 Coronavirus?

- Governor Cuomo and the Coronavirus Models

- How Do False Test Outcomes Affect Estimates of the True Incidence of Coronavirus Infections?

- How Fast Could China's Coronavirus Spread?

References

We've continued following Arizona's experience during the coronavirus pandemic because the state's Department of Health Services makes detailed, high quality time series data available, which makes it easy to apply the back calculation method to identify the timing and events that caused changes in the state's COVID-19 trends. This section links that that resource and many of the others we've found useful throughout the coronavirus pandemic.

Arizona Department of Health Services. COVID-19 Data Dashboard: Vaccine Administration. [Online Database]. Accessed 25 April 2021.

Stephen A. Lauer, Kyra H. Grantz, Qifang Bi, Forrest K. Jones, Qulu Zheng, Hannah R. Meredith, Andrew S. Azman, Nicholas G. Reich, Justin Lessler. The Incubation Period of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) From Publicly Reported Confirmed Cases: Estimation and Application. Annals of Internal Medicine, 5 May 2020. https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-0504.

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 Pandemic Planning Scenarios. [PDF Document]. Updated 10 September 2020.

More or Less: Behind the Stats. Ethnic minority deaths, climate change and lockdown. Interview with Kit Yates discussing back calculation. BBC Radio 4. [Podcast: 8:18 to 14:07]. 29 April 2020.

Labels: coronavirus, data visualization

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.