Are there personality traits that characterize the people who intentionally engage in junk science?

You might not know names like Diederik Stapel, Jan Hendrik Schön, or Haruko Obokata, but to the scientists who work in their respective science fields of social psychology, condensed matter physics and developmental biology, they first rose to prominence and then sunk into infamy thanks to their choices to engage in junk science.

Why did they do it?

All three were recently profiled by Ian Freckleton, who dove into the psychological elements that all three appear to have shared as they engaged in extraordinarily damaging behavior (emphasis ours).

Often individuals who engage in scientific fraud are high achievers. They are prominent in their disciplines but seek to be even more recognised for the pre-eminence of their scholarly contributions. Along with their drive for recognition can come charisma and grandiosity, as well as a craving for the limelight. Their productivity can border on the manic. Their narcissism will often result in a refusal to accept the manifest dishonesty and culpability of their conduct. The rationalising and self-justifying books of Stapel and Obokata are examples of this phenomenon.

When criticism is made or doubts are expressed about their work, these scientists often react aggressively. They may threaten whistleblowers or attempt to displace responsibility for their conduct onto others. Such cases can generate persistent challenges in the courts, as the scientists in question deny any form of impropriety....

Research misconduct often has multiple elements: data fraud, plagiarism and the exploitation of the work of others. People rarely engage in such conduct as a one-off and frequently engage in multiple forms of such dishonesty, until finally they are exposed.

Having had some experience in revealing examples of pseudoscience, we can attest that the personality markers noted by Freckleton appear to us to be pretty spot on.

The consequences of pseudoscientific misconduct however go far beyond the perpetrators' behavior.

This intellectual dishonesty damages colleagues, institutions, patients who receive suspect treatments, trajectories of research and confidence in scholarship.

That's certaintly true in the cases of Stapel, Schön and Obokata, whose scientific legacies have proven to be so damaging that they singlehandedly set back real progress in each of their disciplines. As a result, other scientists wasted far too much of their time in trying to build on their false foundations, which meant that years of good faith effort had to be scrapped. The same scientists had to then add the hard work of reestablishing credibility for their disciplines to the challenge of having to restart their regular work from scratch because of the scholarly misconduct of their corrupt peers.

And all for nothing on the part of the perpetrators, because in the end, all their pseudoscience was exposed as the fraud it was when real science prevailed and they lost their jobs, their titles and their reputations. The sad part is that at least two of the three seem happy with achieving infamy, if their book deals and sales are any indication.

Labels: junk science

In the future, the way your clothes get dry after they are washed may not involve exposing them to heat or prolonged exposure to air, but may instead involve ultrasonic amplifiers, which can make water molecules so excited that they virtually jump out of wet fabric.

Thanks to work being done today at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, in partnership with China's Haier-owned GE Appliances, that possibility is much closer to reality today. (HT: Core77).

Other than the technology itself and the sheer speed that it can dry fabric, the most surprising thing we learned from watching the video above is that 1% of all electricity generated annually in the U.S. today is used to dry clothes after they are washed.

Now, if we can just get the technology behind dessicant-enhanced evaporative cooling into residential air conditioning units, the amount of electricity that Americans consume to keep cool during the summer might be reduced below the 5% of all electricity generated in the U.S. annually that it takes to do the job today, without any loss of quality of life.

Labels: technology

For months, we've been tracking the number of dividend cuts in the U.S. stock market in near real-time, where we've been watching the number of announced reductions reach very worrying levels.

That's why we're pleasantly surprised to be able to report that up to this point in the third quarter of 2016, we're seeing something very positive developing in the market. The cumulative number of dividend cuts that our two near real-time sources have reported for 2016-Q3 through Tuesday, 26 July 2016 is falling both well below what was recorded on the same day of the quarter in the first two quarters of 2016.

And for the first time in 2016, the cumulative number of dividend cuts declared through this day of the current quarter (2016-Q3) is running well below the figures that were recorded in the same quarter a year ago (2015-Q3).

As measured by the number of dividend cuts declared through this point of time through our two main news sources for this information, 2016-Q3 is so far shaping up to be the best quarter of 2016, keeping well within the "green zone" that corresponds to a relatively healthy condition for the U.S. economy. Or perhaps more accurately, where the level of distress in the private sector of the U.S. economy has dropped to levels that are consistent with stronger economic growth.

As analysts, what we want to see over the next several weeks is whether this positive trend continues. As economic observers however, we have to caution that we've found that dividend cuts are a near-real time indicator of the health of the U.S. economy, telling us how businesses perceived their future outlook in the very recent past. Other measures of economic health, such as jobs, are lagging indicators, which means that the high level of distress that we've just seen peak in the form of dividend cut announcements in the previous month may not yet have transmitted through the economy, where bad news for those lagging indicators would still lie ahead.

Data Sources

Seeking Alpha Market Currents Dividend News. [Online Database]. Accessed 26 July 2016.

Wall Street Journal. Dividend Declarations. [Online Database]. Accessed 26 July 2016.

Labels: dividends

Each month, Gordon Green and John Coder of the private sector income and demographics analysis firm Sentier Research report on the level of median household income that they estimate from monthly Current Population Survey data published by the U.S. Census Bureau. We've found their estimates to be an invaluable aid for assessing various aspects of the relative real-time health of the U.S. economy.

We use their reports (the latest is for June 2016) to record a nominal estimate for median household income each month, which as future reports are released, we adjust for inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers in All U.S. Cities for All Items (CPI-U).

Since the beginning of 2016, we've been observing a developing trend for which we now have just barely enough data points to begin making relevant and useful observations, where we find that there are two developing stories. So you can see what we are seeing, here is a chart showing the evolution of median household income in both nominal and real terms from January 2000 through June 2016.

The first and more important story is that nominal median household incomes would appear to have stalled out since December 2015, which is significant because it indicates that the U.S. economy has not been successful in generating higher paying jobs during the last several months.

The second story has to do with the changes in oil and fuel prices, which is greatly affecting the real median household income. In 2015, with those prices falling through much of the year, and particularly in its second half, the effect was to help boost the real incomes of Americans, where those incomes were also growing in nominal terms.

But in 2016, with oil and fuel prices having bottomed and rebounded since the beginning of the year, the effect has been to shrink the real incomes of American households.

Given that 2016 is a presidential election year, you can reasonably expect that whatever trends develop here throughout the year will have an impact on the election's results.

Labels: income

The S&P 500 in the third week of July 2016 ran a bit to the hot side for what our future-based model forecast, but still well within the typical volatility that we would expect. In the chart below, we find that investors are largely continuing to focus on the expectations associated with 2017-Q2 in setting current day stock prices. But we also see that our futures-based model is on the verge of a period of time during which we expect that it will be less accurate than it has been in recent months.

For the last several years, we have been developing a dividend-futures based model for projecting future values of the S&P 500, which incorporates historic stock prices to use as base reference points from which to project the future. More specifically, our standard model incorporates actual S&P 500 closing values that were recorded 13 months earlier, 12 months earlier and 1 month earlier than the period being projected.

In using those historic stock prices however, we have a huge challenge in coping with what we call the echo effect, which results when the historic stock prices we draw upon to create our projections are pulled from periods that experienced unusually high amounts of volatility. A good example of the kind of volatility we're looking to address would be the kind the market saw just a month ago from the market's reaction to the Brexit vote, but much more significantly, on the one-year anniversary of what the market experienced during China's meltdown back in August 2015.

To work around that looming challenge and to try to improve the accuracy of our forecasting model during the periods where we know in advance that our model's forecast results will be less accurate because of the echo effect, we're looking at substituting the actual historic stock prices in our model with prices that reflect the historic mean average trajectory of stock prices.

There's more than one way that we might go about that, but our initial idea is to simply replace the projections of our standard model during the that show the echo effect with the trajectory that would apply as if it were paralleling the mean historic trajectory of the S&P 500 as averaged over each of the last 65 years, which may minimize the discrepancies produced by historic noise between our model's projections and actual future stock prices (absent current day volatility events).

What we're doing assumes that the volatility of the past doesn't have much influence over today's stock prices, which itself is something we strongly suspect, but for which the supporting evidence is less definitive. We also don't know yet to what degree this approach will work, but we'll find out during this quarter. If you follow us, we typically post updates to our projections on Mondays, so you can find out how what we're doing is working almost at the same time we do. Here's the first chart where we're featuring this modified model, which we've imaginatively called "Modified Model 01".

Because the context of how far forward investors are looking in time is so important to determining which of the alternative trajectories that the S&P 500 applies, we make a point of recording the headlines that catch our attention for their market moving potential influence each week. Here are the headlines we identified during Week 3 of July 2016, where much of the news cycle was dominated by reports from the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, Ohio. If you're a serious market investor, you should note how none of them have anything to do with any of the political news from the week, which was a non-event as far as the market was concerned!

- Monday, 18 July 2016

- Tuesday, 19 July 2016

- Wednesday, 20 July 2016

-

- Futures rise on Morgan Stanley, Microsoft results

- Dollar hits four-month high as markets raise bets on Fed rate hike

- S&P, Dow stay on record-setting run; dollar firm - What are the odds of DJI closing higher on 9 consecutive days according to data going back to 2 May 1885? 1 in 818!

- Thursday, 21 July 2016

-

- Dollar drops vs yen as BOJ's Kuroda plays down 'helicopter money'

- Oil down 2 percent as record U.S. stockpiles heighten glut worry

- Intel, transports sap Wall Street's strength - If the Dow had closed up a tenth day in a row, it would have beaten odds of 1 in 1,565! The longest streak of consecutive up days for the DJI is 14, which comes with odds of 1 in 36,005.

- Friday, 22 July 2016

There are some really exciting developments starting to bubble up like perfectoid spaces in mathematics.

Talk about a sentence that we never thought we'd ever write, because:

- The concept of perfectoid spaces has only been around since 2010, having been introduced in a remarkable paper by then-grad student Peter Scholze.

- They've gone from newly introduced exotic concept to powerful tool in an amazingly short period of time.

It's that second thing that's motivated us to write on the topic today.

Here's the best, simplest description we could find of what they are (we've added the links to good starting point references for the different mathematical fields mentioned):

Scholze’s key innovation — a class of fractal structures he calls perfectoid spaces — is only a few years old, but it already has far-reaching ramifications in the field of arithmetic geometry, where number theory and geometry come together.

By far reaching ramifications, they're referring to the use of the new tool to greatly simplify mathematical proofs, such as Scholze did in rewriting a proof of the Local Langlands Correspondence, which had originally required 288 pages, in just 37 pages.

That's possible because of what perfectoid spaces can do in being able to transform very difficult math into much easier math to do, which was Scholze's breakthrough in the field (we've added some of the links in the following passage again for reference purposes).

He eventually realized that it’s possible to construct perfectoid spaces for a wide variety of mathematical structures. These perfectoid spaces, he showed, make it possible to slide questions about polynomials from the p-adic world into a different mathematical universe in which arithmetic is much simpler (for instance, you don’t have to carry when performing addition). “The weirdest property about perfectoid spaces is that they can magically move between the two number systems,” Weinstein said.

This insight allowed Scholze to prove part of a complicated statement about the p-adic solutions to polynomials, called the weight-monodromy conjecture, which became his 2012 doctoral thesis. The thesis “had such far-reaching implications that it was the topic of study groups all over the world,” Weinstein said.

When we discuss math, we like to focus on the practical applications to which it can be put. In this case, mathematician Bhargav Bhatt, who has collaborated with Scholze on several papers, gets to the bottom line for why perfectoid spaces will matter for solving real world problems (reference links added by us again).

Namely, as perfectoid spaces live in the world of analytic geometry, they actually help study classical rigid analytic spaces, not merely algebraic varieties (as in the previous two examples). In his “p-adic Hodge theory for rigid-analytic varieties” paper, Scholze pursues this idea to extend the foundational results in p-adic Hodge theory, such as Faltings’s work mentioned above, to the setting of rigid analytic spaces over Qp; such an extension was conjectured many decades ago by Tate in his epochmaking paper “p-divisible groups.” The essential ingredient of Scholze’s approach is the remarkable observation that every classical rigid-analytic space over Qp is locally perfectoid, in a suitable sense.

Which is to say that a whole lot of problems that have proven to either be very difficult to solve or have evaded solution by other methods might yield easily to solution by the newly developed mathematical theory of perfectoid spaces. For a field like mathematics, that's a huge deal!

We'll close with Peter Scholze speaking on perfectoid spaces in 2014.

Labels: math

We have a new example of junk science today, which might perhaps be better described as bad analysis that checks off one of the more significant boxes in our junk science checklist. Specifically, today's example trips over the checklist category for Inconsistencies, which is where we are most likely to find the effects of deceptive maths and abusive statistics.

| How to Distinguish "Good" Science from "Junk" or "Pseudo" Science | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Science | Pseudoscience | Comments |

| Inconsistencies | Observations or data that are not consistent with current scientific understanding generate intense interest for additional study among scientists. Original observations and data are made accessible to all interested parties to support this effort. | Observations of data that are not consistent with established beliefs tend to be ignored or actively suppressed. Original observations and data are often difficult to obtain from pseudoscience practitioners, and is often just anecdotal. | Providing access to all available data allows others to independently reproduce and confirm findings. Failing to make all collected data and analysis available for independent review undermines the validity of any claimed finding. Here's a recent example of the misuse of statistics where contradictory data that would have avoided a pseudoscientific conclusion was improperly screened out, which was found after all the data was made available for independent review. |

The following analysis shows the importance of the work that is often done in near-anonymity to replicate and validate the results of analysis where unique findings are made, which is only possible when the data behind the analysis is available. Unfortunately, today's example of junk science won't be the last time we'll be discussing an example in this category, thanks to the special efforts of a repeat offender.

Let's get to it then, shall we?

Everyone knows about lies, damned lies, and statistics. The quote has been attached to Mark Twain who apparently attributed it to British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli. It remains among popular clichés because there is universal truth to it, a sort of caveat emptor lying in the background whenever one consumes an argument. Nowhere is that more the truth than economics and finance, disciplines almost (nowadays) entirely populated with statistics and very little else.

Given the rather extreme nature of the times, extreme statistics are more prevalent perhaps than at any other point. They run the spectrum, as do human intentions, from the purely mistake to the malicious. The better stats, as the best lies, are often difficult to discern because they contain a great deal of truth; requiring a great deal of further analysis and scrutiny to unpack the error or mistake. Sometimes, however, it takes very little effort (reflecting both on the numbers and the person wielding them).

Prominently displayed on the front page of Yahoo! Finance recently was an article whose purpose was just so barely disguised. You can and should read the whole piece, but the gist is essentially that we shouldn't worry about very high valuations to the current stock market because valuations aren't so simple. The expert quoted in the article declares that PE's at this point, well above 20x, "do not contradict the bullish case for stocks." The reason is low inflation and related low interest rates; an argument proposed and reiterated many, many times before.

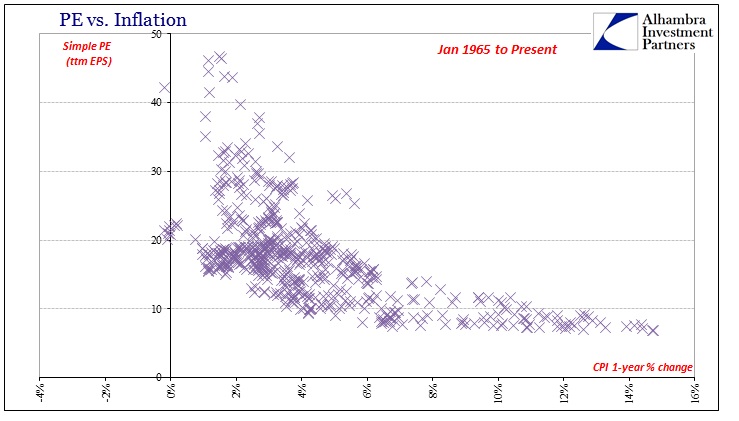

There are statistics for this view, including a neat chart showing the relationship between PE's for the S&P 500 and their coincident inflationary circumstances (represented by the 1-year change in the CPI).

Using Robert Shiller's data for the historical S&P 500, inflation, and earnings, I recreated the same chart with very nearly the same results.

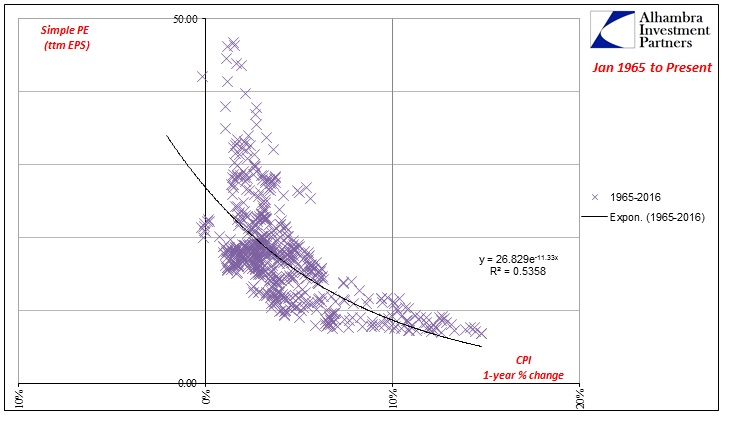

Running a simple, exponential regression (a polynomial regression finds a better fit, but raises the objection of being fitted), you do find a relationship that argues in favor of the proposition; inflation and PE's are to some degree negatively correlated.

Because I found the same as projected in the article, I can confidently declare it nonsense. I did not test for statistical significance in the regression because it simply wasn't necessary; this argument falls apart long before the math.

This is simply a case of, at best, circular logic or, at worst, intentional obfuscation. The first clue is the time frame itself, starting right on the cusp of the Great Inflation. Given the much further history of Shiller's data, we need not be so discerning. Going back further to the 1870’s provides a much different result.

The regression using this full dataset is far, far less compelling. You don’t even need the regression to see the distribution – the densest area of the scatterplot above is between 0% and 5% inflation and 10 and 20 times earnings.

There is still, however, some mathematical relationship even though the R-squared is especially low. If we perform our own transformations in framing the time period, this apparently inverse correlation is revealed more clearly. If we instead end with only through the last part of the Great Inflation, to December 1979, we actually find very little to support the hypothesis.

There is actually very little reasonable correlation between inflation and PE's to this point in history; a slightly detectible hint but without a whole lot of variation. Notably absent are those more extreme, higher valuations that perform the upward transformation in the original regression. Moving forward in time to December 1994, we find some indication of a greater cluster starting to move up the axis (the Great "Moderation"), but still nothing like the original premise.

It isn’t until we add the latter half of the 1990’s and the dot-com bubble that these “positive” valuation outliers suddenly appear (the rest of them don’t show up until, ironically, the Great Recession when earnings fell very far in coincidence to disinflation and even negative inflation). This is, of course, wholly unsurprising.

But there is more to the deception, which is why the Great Inflation period was included. If we isolate just age of asset bubbles, the relationship once more disappears almost entirely.

A regression function that plots almost vertically means that PE valuations have moved around almost totally independent of the CPI. In other words, without including the Great Inflation period and its immediate aftermath to fill in the bottom right there is again no mathematical significance between inflation and PE's. In isolation, the market valuation since 1995 just doesn't bear any resemblance to inflation, leaving it as a function of some other independent condition (such as monetary agency). It is only by included the “other” extreme of low valuations and high inflation of the 1960’s and 1970’s that gives this assertion of causation the thin veneer of validity.

But that is hardly the same scheme as what was proposed. What these figures show is really much different; from 1965 forward, the most that can be said is that there were generally lower valuations as high consumer inflation raged before the 1980’s. After 1995, there was generally much higher valuations and lower inflation. It does not follow, then, that valuations are determined by inflation – at all. Causation would appear to be among the “error” terms or more likely independent variables left out entirely, which is what the full data set suggests. There is no data suggesting what valuations would do with very high inflation (recorded in the CPI) after 1995 because it hasn't happened; likewise with low inflation during especially the 1970’s.

These are cases, then, that must be taken in isolation, not as a universally-applied “rule” or even suggestion. To add one is a blatant misuse of correlation, again an indictment first suggested by starting with and only including the period after January 1965. Including the Great Inflation and its opposite extreme muddies the interpretation because you can't immediately discern the separate circumstances as separate. To claim that low inflation after 1995 supports high valuations is tantamount to wholly biased selectivity; there is no evidence to prove (or disprove) the assertion, an invalidation in statistics as well as basic logic. All the math shows is that there was low inflation.

That is really what the full data tells us, with one very important contextual addition. Comparing the years without the dot-com bubble and finding very little relationship means that it is only through the high valuations of the dot-com era (and to a lesser extent more recently) that gives this idea its apparent (and still wrong) relevance. That would mean the original premise contained in the article is using the incident high valuations of the dot-com bubble because they occurred during a period of low CPI inflation to propose that high valuations today aren't threatening because we still find low CPI inflation. It essentially advises that the last big stock bubble justifies why we shouldn't be worried about another one.

That was Twain's, as Disraeli's, point all along. If you have a strong argument you don't need to resort to bad math to make it; bad math is instead used, often intentionally, to obscure the weakness.

References

Snider, Jeffrey P. Valuation Fallacies. Alhambra Investment Partners. [Online Article]. 18 July 2016. Republished with permission.

Shiller, Robert. U.S. Stock Markets 1871-Present and CAPE Ratio. [Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 18 July 2016.

Political Calculations. How To Detect Junk Science. [Online Article]. 19 August 2009.

Labels: junk science

Updates! Scroll down....

Nearly a month ago, we presented our "most likely" prediction for how the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis will revise the U.S.' Real Gross Domestic Product on Friday, 29 July 2016.

Let's recap what we forecast, picking things up from after we described how we went from estimating the "maximum potential" size of the revision to the "maximum likely" size of it, before we drilled down to what we think will be the "most likely" amount by which real GDP will be revised through the fourth quarter of 2015:

But the "maximum likely" revision of -1.4% of previously reported GDP through 2015-Q4 is not the "most likely" size of the upcoming revision to the nation's GDP will be, because the BEA's plans for the revision of the national level GDP data will only cover the period from 2013-Q1 through 2016-Q1.

That means that it will miss the discrepancy that opens up in 2012-Q3 and 2012-Q4 between the just-revised state level GDP and previously indicated overseas federal GDP and its previously recorded national level GDP. That discrepancy is just over $55.1 billion in terms of constant 2009 U.S. dollars in 2012-Q4, which itself is over 24% of the full $225.7 billion discrepancy that our previous calculations indicates between the pre-revised national level real GDP and the post-revised state level GDP data through 2015-Q3.

Because the BEA won't be including that $55.1 billion portion of the discrepancy from 2012, the "most likely" size of the revision that it will report at the end of July 2016 is therefore -1.1%, which is 24% less than the "maximum likely" revision of -1.4% we previously calculated.

After the BEA's annual revision of GDP for the 50 states and the District of Columbia on 14 June 2016, there is only one factor left that can affect the amount by which the BEA will actually revise the nation's total real GDP next week - the contribution of overseas federal military and civilian government activities, or as we've described it, the "hidden GDP of war".

There are three scenarios in how that one factor can play out:

- If that contribution is greater than what the BEA has previously indicated, the amount by which real GDP through 2015-Q4 will be adjusted will be smaller. So instead of being reduced by 1.1% as we've projected to be "most likely", it would instead be reduced by a smaller percentage, or in the very unlikely case that contribution is much, much greater, real GDP through 2015-Q4 could be adjusted upward. For this scenario to occur, it would mean that the U.S. government was much more engaged in fighting wars overseas in a way that adds to the nation's GDP than it has previously indicated. This is the "under" scenario.

- If that contribution is less than that the BEA has previously indicated, the amount by which real GDP through 2015-Q4 will be adjusted downward will be larger, going in the direction of what we calculated would be the maximum likely revision. For this scenario to occur, it would mean that the U.S. government was engaged in less "productive" military and civilian government activities overseas than it has previously indicated. This is the "over" scenario.

- If the contribution is the same as what the BEA has previously indicated, then we'll see the "most likely" scenario we calculated be the actual result. Real GDP through 2015-Q4 would be decreased by about 1.1% from the level that was recorded earlier this year on 29 March 2016. This might be considered the "null" scenario.

To make that question more interesting, we asked our most dedicated readers [1] to click through and answer a SurveyMonkey poll, which we've now closed. The results of that poll are presented in the following chart.

As you can see, our poll produced a 40-40-20 split. 40% of the poll participants indicated they thought Scenario #1 was more likely, 40% predicted Scenario #2 would be a reality, and 20% believed in the Scenario #3 "no change from our forecast outcome" outcome.

While those results seem nearly split down the middle, what they really indicate is that the majority of the poll participants believe that the actual adjustment to real GDP through 2015-Q4 will be different from our "most likely" forecast for the size of the July 2016 national revision. What is equally split down the middle is the direction in which it will be adjusted, with no clear collective prediction emerging from our poll.

Where is Philip Tetlock when you need him?

Notes

[1] We had problems with generating working code to embed the survey directly in our post, so we were stuck with providing a link for readers to click through to participate in the survey. That's the sort of hassle that only the most dedicated readers would endure, so we greatly appreciate the extra effort on the part of all the participants who registered their own prediction for how this one aspect that will affect the actual size of the upcoming GDP revision. Thank you!

Update 27 July 2016: This is so cool! We had an extended contact today with an analyst who works for the BEA, who wanted to know more about how we came up with our estimate of how real GDP would change using the BEA's recently revised regional account data.

That was fantastic timing, because we just happened to have our spreadsheet open because we were updating it with state level GDP data from 2016-Q1 that was just released today.

In going over that material, we discovered a problem that threw off our calculations, with the effect that the results we had obtained weren't matching what they were getting from 2014-Q3 onward in replicating our analysis. We were able to trace the problem back to the GDP deflator that we used to convert nominal GDP data to inflation-adjusted "real" data, where we were multiplying the nominal data by the GDP deflator data for the national level data (the data whose revision is set to be published on Friday, 29 July 2016) instead of the GDP deflator data that applies for the aggregate 50 states plus Washington DC, which just happened to be in the spreadsheet column next to it.

After we made the appropriate correction, all our results from 2014-Q3 onward snapped into place and all results matched, from the period from 2005-Q1 through 2014-Q2, where there was never any problem, and now from 2014-Q3 through 2015-Q4! The following chart shows the latest and greatest for what we expect from Friday's GDP revision based only on the state level GDP revision from June!

As for the outcome of the analysis, the error we made with using the incorrect GDP deflator overstated the amount by which real GDP is likely to be revised by 0.5% of GDP, so instead of the maximum likely change of -1.4% that we had previously calculated, the maximum amount by which national GDP might change as a result of the revisions the BEA has made to its GDP data for the 50 states plus Washington DC is -0.9%, with the maximum discrepancy now taking place in 2013-Q3. This data is indicated in the chart above by the dark-green line.

But since the BEA's national revision will cover the period from 2013-Q1 to the present, the revision of the national level GDP will not include the now-confirmed $55 billion discrepancy that opens up between the national GDP data and the national aggregate state level GDP in 2012. We are therefore now estimating that the most likely revision that will be made to the national GDP data on Friday, 29 July 2016 will be an adjustment of -0.6% in 2013-Q3. This data is indicated in the chart above by the bright red line (and the blue arrow at 2013-Q3).

We'd like to thank everyone who provided their useful assistance in getting to this point - in terms of collaborative effort, this has been one of the biggest projects we've had the pleasure of working on since launching Political Calculations. It's always exciting when we get to break brand new ground and do analysis that was never possible before, and we appreciate your shared enthusiasm!

On a final note, if you happened to have come across this post by way of Econbrowser, you might want to pass along information back to the author who pointed you in this direction that their observations have been described as "not relevant". We're pretty sure that particular author hears that a lot ....

There's more that we'd like to be able to discuss on the topic of the upcoming national-level GDP revision, but that will have to wait until after that data is released. Until then, what you see above represents the most that anyone can reasonably glean about what the revision will look like based only on data that is already available to the public.

Update 29 July 2016: The verdict is in! The chart below shows the revisions in national level real GDP from 2013-Q1 through 2015-Q4....

Compared to our final pre-revision prediction from 27 July 2016, we were off by 0.1% of GDP through 2015-Q4, where we had previously projected no change.

More significantly however, national-level real GDP was increased by 0.2% of its previously reported figure in 2013-Q3, where the aggregate GDP data for the 50 states and the District of Columbia had instead indicated that a 0.6% of GDP decline for that quarter was most likely. That means that the amount of GDP that the U.S. generated in that quarter from Overseas Federal Military and Civilian Government Activities was revised to be significantly much higher than the BEA had previously indicated, in effect, adding an additional 0.8% of GDP on top of what the BEA now indicates was generated within the actual territory of the United States.

We'll dig deeper into the national-level GDP revision periodically over the next several weeks!

Finally, our congratulations to the 40% of respondents in our poll who chose the "under" scenario - well done!

Labels: gdp forecast

Last week, while visiting Bozeman, Montana, Matt Kahn looked out over all he surveyed and said:

I'm in Bozeman, Montana. While there are 40,000 people in this city. I see a lot of open space. Google taught me that Montana has 380,000 square kilometers of land. Suppose that 50% of that can be built upon. Suppose we built up at Hong Kong's density of 7000 people per square mile. So, we would re-create dense cities at a higher latitude. Let's do some math. 190,000*7000 = 1.33 billion people could live in Montana. This migration and real estate construction would create great wealth. Now, given that the U.S population has only 340 million people --- we could open up migration for those who could jump over Don Trump's wall and house them. This example is meant to show folks how urbanization facilitates adaptation. We need to use our resources more efficiently.

Why do I focus on Montana? It is towards the North and it is off the coast and there is plenty of land here. Yes, this land has some economic activity taking place on it right now but urban use would be more valuable. I am now working on a natural disaster project with Leah Boustan and Paul Rhode and once I can access our disaster data, I will update this post to see whether Montana is exposed to more disasters than would be predicted given its size.

We love this kind of blogging from econ professors because it makes for a quick and dirty tool development project! We've taken Kahn's algebra and built a tool to do it, where anyone can substitute the default data for Montana and Hong Kong (Hong Kong's population density is nearly 7,000 people per square kilometer) with the region or population density of their choice. Including you, where if you're accessing this post on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click through to our site to access a working version of the tool so you can!

Since the topic of disasters came up, the biggest lurking natural disaster that has been proposed for Montana would be an eruption of the Yellowstone supervolcano, which in terms of potential scale, would make the plot of a big budget Hollywood disaster movie look like a straight to video animated sequel to a less-than-popular children's movie.

The timebomb under Yellowstone: Experts warn of 90,000 immediate deaths and a 'nuclear winter' across the US if supervolcano erupts

- It could release 1 ft layer of molten ash 1,000 miles from the National Park

- It would be 1,000 times as powerful as the 1980 Mount St Helens eruption

- A haze would drap over the United States, causing temperatures to drop

- Experts say there is a 1 in 700,000 annual chance of a eruption at the site.

The odds of such an event are everything in determining whether we should build out Montana to be the home of 1.33 billion people.

Labels: environment, tool

The second week of July 2016 was one of those rare weeks when our futures-based model for projecting the future closing value of the S&P 500 was very nearly dead on target for every day of the week, as long as you recognize that target was fixed by investors focusing on the second quarter of 2017 (2017-Q2) in making their current day investment decisions.

You don't have to take our word for it. We animated what our model forecast and how the S&P 500 actually performed for your entertainment, provided of course that you're entertained by watching the projected trajectories that our futures-based model generates flop about like a fish while, at the same time, the actual trajectory that the S&P 500 takes is overlaid on top of those projections. If you're viewing this post on a site that republishes our RSS news feed and the animation doesn't play, we've posted a YouTube video version of the animation as well.

In putting the animation together, we're taking advantage of a unique opportunity to show the formation of an echo on our model's projections of the future, which developed as a direct response to the market's reaction to the Brexit vote outcome on 24 June 2016 through 25 June 2016.

Starting on 21 June 2016, the animation shows first what the future looked like going into the Brexit vote, then how our model's projections of the future changed in response to the aftermath of the Brexit vote. That outcome shows up as an echo in our model's projections, which appears one month after the actual event occurred. The echo is the result of our model's use of historic stock prices as the base reference points from which we project the future for stock prices.

Beginning on 27 June 2016, the animation then shows the trajectory of the S&P 500's closing daily value on each trading day, which reveals how stock prices reacted as investors shifted their forwarding looking focus from one point of time in the future to another.

The first takes place as a Lévy flight from 27 June 2016 to 30 June 2016, when investors shifted their attention from the expectations associated with 2016-Q3 in the immediate aftermath of the Brexit vote to the more distant future of 2017-Q1.

The stock market's focus then held on 2017-Q1 from 30 June 2016 through 7 July 2016. On 8 July 2016, the collective focus of investors shifted in a second Lévy flight, from 2017-Q1 to the even more distant future of 2017-Q2, where it held through the rest of the week, very closely matching the exact trajectory our futures-based model forecast associated with investors being very closely focused on that future quarter.

From the perspective that investors simply appear to have maintained their focus on 2017-Q2 through the entire week, it was a pretty boring week overall, even if some market observers were perplexed as to why stock prices behaved as they did in the face of a week of turmoil in many areas of the world.

But for the U.S. stock market, here is the news that we flagged as being the significant for the S&P 500 in Week 2 of July 2016.

- Monday, 11 July 2016

-

- Fed's George says U.S. interest rates are currently too low - to which U.S. investors responded by ignoring Fed's George (see next headline!)

- S&P 500 hits record high on economy, earnings bets

- Tuesday, 12 July 2016

- Wednesday, 13 July 2016

-

- Fed should be patient in removing monetary accommodation; Kaplan - also Fed's Kaplan urges 'slow, gradual, careful' approach on rates

- S&P 500, Dow end at record highs despite caution; oil falls

- Fed's Harker now sees just up to 2 rate hikes this year - Harker is becoming more dovish. Back in March, he was expecting "at least three".

- Thursday, 14 July 2016

-

- Fed's Lockhart says two rate increases still possible this year - also, Fed's Lockhart: Brexit, uncertainty, require patience on rates

- U.S. Fed buys $7 billion of mortgage bonds, sells none - follow this link. It turns out that the Fed's QE program aimed at lowering U.S. mortgage rates never really ended, even though top-line growth in the Fed's balance sheet flattened out to show little change from month to month - they've managed to keep the mortgage rate-lowering portion of their QE program going at a low level progressively changing the composition of their holdings.

- JPMorgan-powered rally pushes S&P, Dow to new highs - not a bad day for JPM, which also saw the headline "JP Morgan ready to lend seven billion euros for Monte dei Paschi bad-loan deal: paper, which would also boost confidence for Europe's struggling banking industry.

- Friday, 15 July 2016

If you haven't seen it yet, the following video shows the optical illusion of the year (HT: Marginal Revolution).

And if you want to know how it works, the next video reveals the secrets behind the illusion (HT: Core77):

Labels: technology

After visualizing how U.S. GDP has evolved since the first quarter of 1947, both with and without the contribution of the federal government and also state and local governments, we couldn't help but notice that the U.S. federal government's contribution to GDP in recent years was far below the amount of money that it spends.

So today, we're digging deeper into the data and going the extra mile to illustrate the amount of federal spending that actually ends up going to a productive end, as determined by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Our first chart shows the U.S. government's nominal total spending along with the nominal amount the BEA indicates contributes positively to the nation's Gross Domestic Product.

In our next chart, we've calculated the percentage of GDP that is generated for every dollar of the U.S. federal government's spending for each quarter from 1947-Q1 through 2016-Q1.

Over this period, we see that in the years immediately following World War 2, around 65% of the U.S. government's spending added to the nation's GDP. After briefly dipping in 1950, the U.S. government became a powerhouse contributor to the nation's GDP in the 1950s, as it began rebuilding the U.S. military and launched the U.S. interstate highway system, where suddenly, as much as 97.3% of the U.S. government's spending contributed to the nation's productive output.

After that initial surge, the contribution of U.S. government spending to GDP began declining. Slowly at first, it declined steadily to 74.8% in 1967, after which it began to deteriorate much faster, plunging to 44.8% in 1975, as the U.S. government implemented the Medicare and Medicaid welfare programs. Although it leveled out somewhat after 1975, it continued declining until bottoming in 1981 at 42.8%.

From 1981 through 1988, federal government spending made a more positive contribution to the nation's GDP, rising to 47.3%. This period coincides with a period in which the U.S. military was modernized and expanded.

But in the decade that followed, the contribution of the U.S. government's spending to the nation's GDP began diminishing again, falling to 32.3% in 1999, as the U.S. military shrank following the end of the Cold War, holding at that level through 2001. It then briefly rose to peak again at 37.2% in 2005, largely due to the aftermath of the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks the subsequent expansion of the U.S. military to fight wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. After 2005, it held mostly flat through 2008, varying with military actions overseas.

After 2008 however, the U.S. government's spending contribution to GDP resumed its downward trend, falling to 30.1% through the first quarter of 2016, where now, just over 30 cents of every dollar spent by the U.S. government adds to the nation's GDP. During this period, U.S. military spending has been sharply reduced, while at the same time, additional government spending was devoted to expanding the Medicaid welfare program and subsidizing health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, which the BEA's GDP data suggests does not positively contribute to the growth of the U.S. economy.

We find then that over the last 60 years, the U.S. government has gone from a period where it was a powerhouse contributor to the nation's economy, where nearly every dollar it spent boosted the economy, to one in which nearly 70 cents of every dollar it spends is not considered to add to the productive output of the nation.

Data Source

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. National Income and Product Accounts. Tables 1.1.5 and Table 3.2. [Online Database]. Last updated 28 June 2016. Accessed 12 July 2016.

Labels: data visualization, gdp

Not long ago, we received an interesting request from one of our longtime readers:

Could you do an article and specifically a graphic that would show what the US economy would look like in GDP terms without the Federal, State and Local governments? Say from 1970 to present? It would be informative to see the GDP growth less government spending.

We'll go a step further, because the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis makes most of this data available on a quarterly basis going back to 1947. In our first chart below, we'll track the evolution of nominal GDP from 1947-Q1 through 2016-Q1, in which we can extract both the contributions of the federal government and also of state and local governments.

Because the U.S.' Gross Domestic Product has typically grown at exponential rates over time, we'll also visually present this same nominal data on a logarithmic scale, which indicates equal amounts of percentage change, as opposed to the more common linear scale, which indicates equal units of numerical change.

The two charts above represent the nominal GDP for the U.S., which is to say the Gross Domestic Product that was measured in the terms of the actual prices in U.S. dollars that people and businesses actually paid for goods and services in the periods where the data was recorded.

But whenever we present nominal data like this, we also invariably get requests to adjust the values to account for the effects of inflation over time.

That can be problematic because there is more than one kind of inflation measure. Should we use the GDP deflator? The Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers? The Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers? Personal Consumption Expenditures? Trimmed Mean Personal Consumption Expenditures? The Median Consumer Price Index? What about the Sticky Price Consumer Price Index?

And once we do select the type of inflation to adjust for, we still need to select which year's U.S. dollars to reference all the calculations to. Should we use 2016? How about 2000? Or perhaps the bicentennial year of 1976? Maybe we should go back to the beginning of the quarterly GDP data series and use 1947? It seems that no matter which time period we might select, it will invariably be out of date, or soon will be, especially for people who are always most familiar with buying and selling things priced in terms of current day nominal U.S. dollars!

If these considerations sound somewhat complicated, it is because selecting an appropriate measure of inflation for which to adjust nominal price data can be challenging, where you can get quite different results from using different measures. As economic historians, these considerations are why we strongly recommend that regardless of which inflation measure you might choose to adjust nominal data, it is essential to *always* reference nominal data sources because they are not subject to what may be arbitrary choices on the part of the analyst doing the calculations.

Nominal price data has the singular benefit of never changing while also representing the documented costs that real people participating in the economy at the time in a given period of interest would have paid, and as such, will be the only form of such price data that can be confirmed or validated using contemporary accounts and other historic references, which is essential for appreciating the true context in which their participation in the economy occurred. Believe it or not, there are economics professors at major universities who don't themselves have a firm grasp of these kinds of considerations, but whose students have never-the-less benefited from their having incorporated our comments on this specific topic into their presentations.

In this case, we'll default our presentation to match the choice of the data jocks at the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, who are using the GDP implicit price deflator as expressed in terms of chained 2009 U.S. dollars. If you'd like to see this data presented to be adjusted to be in terms of some other inflation measure, we've linked to the source of the nominal data below, and you should find the math of doing the inflation adjustment yourself to be super easy, even if the choice of which inflation measure to use may not be quite so simple. Our chart showing the Real GDP of the U.S. economy, with and without the contribution of the U.S. government as well as state and local governments, on a linear scale is below.

In the chart above, since the BEA only provides detailed Real GDP data on the contributions of the U.S. Federal Government and State & Local Governments back to 1999-Q1, we only show their individual contributions back to that quarter. The BEA does however provide data on the combined contribution of all governments in the U.S. back to 1947-Q1, so we can get a good idea of the private sector's GDP output back to that time.

We'll wrap up this post with the same inflation-adjusted data presented on a logarithmic scale.

In the course of putting these charts together, we did find something else interesting in the data, which we'll follow up with in the very near future!

Update 25 July 2016: Our discussion of the BEA's real, or inflation-adjusted data above should have carried the warning that their Chained Weighted constant dollar indexes are only truly additive in their base reference year, which means that the subcomponents of GDP will only add up to equal the total estimated real GDP value in that year. For the relevant charts presented above, that year is 2009.

Nominal GDP doesn't have that issue, which is another reason why nominal GDP data should always be referenced in this kind of presentation. If however you need a quick approximation of what real GDP would be with or without such a particular contribution from one of its components, then a simple subtraction method can get you in the right ballpark (say if you want to create a counterfactual that fits well within the statistical margin of error of a more precise calculation), but with the penalty of less accuracy as you get further and further away from the base reference year. As a general rule of thumb, if you stay within five years of the base reference year for that kind of application, you should be in good shape for that kind of back of the envelope calculation.

But what if you get far outside that range? In those cases, the errors can grow quite large, with the largest errors typically being the furthest away from the base reference year. The following chart shows that effect.

Unlike the author of this particular chart, we are quite happy to acknowledge whenever we have presented errors in our analysis, even minor screw ups like the one above! We would also like to thank the author for revealing, through their more precise approximation of the private sector contribution to real GDP, that the real economic growth of the private sector of the U.S. economy has been considerably more anemic in recent years than was indicated by our simple subtraction method-based approximation.

Data Source

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. National Income and Product Accounts. Tables 1.1.5 and Table 1.1.6. [Online Database]. Last updated 28 June 2016. Accessed 12 July 2016.

Labels: data visualization, gdp

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.