The U.S. Federal Reserve finally backed off from hiking short term interest rates in the U.S., choosing to keep the target range of 2.25%-2.50% for the Federal Funds Rate.

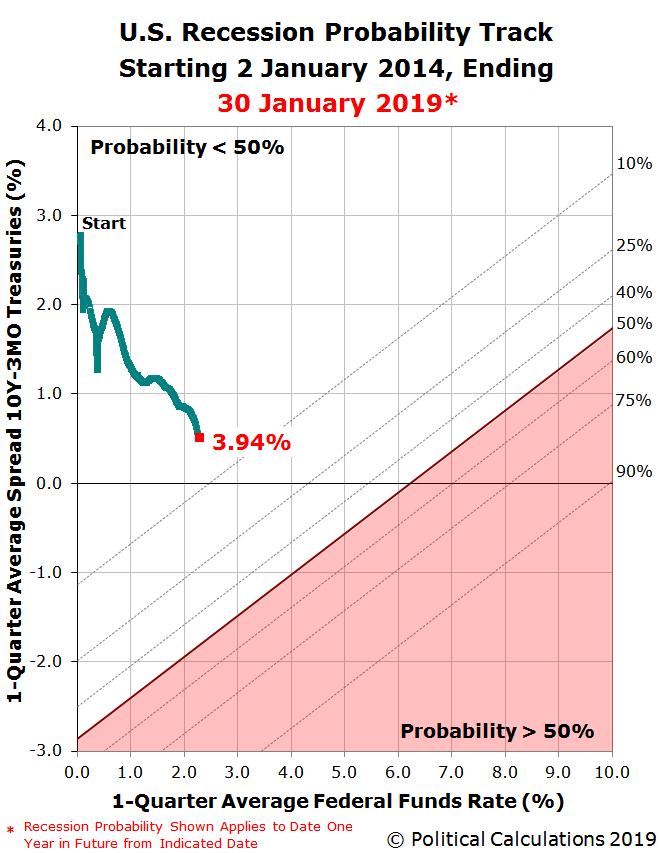

The risk that the U.S. economy will enter into a national recession at some time in the next twelve months now stands at 3.9%, which is up by roughly one-and-a-half percentage points since our last snapshot of the U.S. recession probability from late December 2018. The current 3.9% probability works out to be nearly a 1-in-25 chance that a recession will eventually be found by the National Bureau of Economic Research to have begun at some point between 30 January 2019 and 30 January 2020, according to a model developed by Jonathan Wright of the Federal Reserve Board back in 2006.

The Fed's decision to hold the Federal Funds Rate steady comes as the bond market has been responding to deteriorating conditions in the global economy, particularly in China and in the Eurozone. The U.S. Treasury yield curve, as measured by the spread between the 10-Year and 3-Month constant maturity U.S. Treasuries, has been flattening in response to those global conditions as bond investors would appear to pursue a flight to relative quality investing strategy.

The Recession Probability Track shows where these two factors have set the probability of a recession starting in the U.S. during the next 12 months.

We anticipate that the probability of recession will continue to rise in 2019, with the Fed bowing to reality and putting its previously planned series of quarter-point rate hikes on hold. The Fed has also indicated that it is weighing an early end to its plans to shrink its balance sheet, where their decision to do so will remove the additional pressure it has been generating toward flattening the yield curve through quantitative tightening.

The questions now are whether they put the brakes on fast enough to avoid having the U.S. economy fall into recession, and whether the recession forecasting model we're using is accurately reflecting the nation's risk of recession.

On that second point, Wright's model is based on historic data where recessions have generally started at much higher interest rates than they are today, and which also doesn't consider the additional quantitative tightening that the Fed might achieve through reducing its holdings of U.S. Treasuries, where we're stretching the model's capability to assess the probability of recession in today's economic environment. It is quite possible that the model is understating the probability of recession starting in the U.S. when the Federal Funds Rate is as low as it is today.

Analysts at financial services firm Société Générale (SocGen) have estimated that the Fed's balance sheet shrinking has added the equivalent of 3% to the Federal Funds Rate, making the Fed's "Shadow Federal Funds Rate" as high as 5.45%.

We re-did the recession forecast math with the same Treasury yield spread and SocGen's shadow rate estimate and found that Wright's model would project a probability of recession starting between 30 January 2019 and 30 January 2020 of 23.2%, or nearly 1-in-4 odds if the shadow rate should turn out to be a real thing.

If you would like to also get in on the game of predicting the odds of recession starting in the U.S., please take advantage of our recession odds reckoning tool, which like our Recession Probability Track chart, is also based on Jonathan Wright's 2006 paper describing a recession forecasting method using the level of the effective Federal Funds Rate and the spread between the yields of the 10-Year and 3-Month Constant Maturity U.S. Treasuries.

It's really easy. Plug in the most recent data available, or the data that would apply for a future scenario that you would like to consider, and compare the result you get in our tool with what we've shown in the most recent chart we've presented. The links below present each of the posts in the current series since we restarted it in June 2017.

Previously on Political Calculations

- The Return of the Recession Probability Track

- U.S. Recession Probability Low After Fed's July 2017 Meeting

- U.S. Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up After Fed Does Nothing

- Déjà Vu All Over Again for U.S. Recession Probability

- Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up as Fed Hikes

- U.S. Recession Risk Minimal (January 2018)

- U.S. Recession Probability Risk Still Minimal

- U.S. Recession Odds Tick Slightly Upward, Remain Very Low

- The Fed Meets, Nothing Happens, Recession Risk Stays Minimal

- Fed Raises Rates, Recession Risk to Rise in Response

- 1 in 91 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before August 2019

- 1 in 63 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before September 2019

- 1 in 54 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before November 2019

- 1 in 42 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before December 2019

- 1 in 25 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before February 2020

Labels: recession forecast

The near-real time sources that we track for dividend cut announcements is signaling that something wicked is happening within the U.S. oil and gas industry.

Setting the scene for context, the fourth quarter of 2018 ended with an ominous undertone in an otherwise positive year for dividend paying stocks in the United States:

By far and away, the oil and gas industry saw the greatest amount of distress during the fourth quarter of 2018, accounting for 63% of our sample and coinciding with a significant decline in oil prices during the quarter as global demand diminished. The financial sector, including Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs), came in second with 17.4% of the dividend cuts in our sample, where the Fed's rate hikes negatively impacted eight of these interest rate-sensitive firms. Food producer and the manufacturing sector each recorded 2 dividend cutting firms each (manufacturing included the highly distressed GE), while the technology, mining, consumer goods and utility industries rounded out our sample with just one dividend cut recorded in each.

Now that January 2019 is nearly complete, we thought it might be worthwhile to check our two main sources for near-real time sample of dividend cut announcements to see how things are faring so far in the first quarter of 2019.

Compared to the first quarter of 2018, we find that the pace of dividend cut announcements is coming in above the level we recorded through the same point of time of the current quarter.

What really stands out in the underlying data however is that all of the firms in our sample that have declared dividend reductions in January 2019 are in the oil and gas sector of the U.S. economy. Here's the list of firms and links to their announcements.

- MV Oil Trust (NYSE: MVO)

- Sabine Royalty Trust (NYSE: SBR)

- BP Prudhoe Bay Royalty Trust (NYSE: BPT)

- VOC Energy Trust (NYSE: VOC)

- Mesa Royalty Trust (NYSE: MTR)

- Permian Basin Royalty Trust (NYSE: PBT)

- Cross Timbers Royalty Trust (NYSE: CRT)

- PermRock Royalty Trust (NYSE: PRT)

- CSI Compressco (NASDAQ: CCLP)

- Seadrill Partners (NYSE: SDLP)

- SandRidge Mississippian Trust I (NYSE: SDT)

- SandRidge Mississippian Trust II (NYSE: SDR)

- SandRidge Permian Trust (NYSE: PER)

- Kimbell Royalty Partners (NYSE: KRP)

- Dynagas LNG Partners LP (NYSE: DLNG)

This concentration of dividend cuts within the oil and gas industry is largely a result of an economic situation that has been developing in the global economy since late 2017, where several large economies have been experiencing a marked deceleration in economic growth, such as China and the Eurozone, which noticeably deepened in the last quarter of 2018.

Stimulated by tax cuts passed in late 2017, the U.S. economy was generally able to avoid a similar economic deterioration throughout much of 2018, but not entirely. The global economic deceleration has reduced the demand for oil and gas, which in turn, has lead to a steep decline in the price of U.S.-produced oil and gas products. Lower revenues have shrunk profits and cash flow in the industry, prompting the elevated level of dividend cuts we've seen in both the fourth quarter of 2018 and in January 2019.

Pointing to potential ripple effects from the intrusion of the global economy's distress into U.S. oil-producing states, the increased level of distress in the industry also helps explain something we've observed in state-level housing markets in the U.S., where the oil-producing states of Texas, North Dakota, and Louisiana have seen particularly sharp declines in existing home sales since September 2018, coinciding with the downturn in the health of the oil and gas industry in the last quarter of the year.

Do you suppose the Fed is taking these recent developments into consideration at its meeting today?

We'll follow up with our regular Dividends by the Numbers series when the data for the entire U.S. stock market sometime next week.

Update 1 February 2019: Expanding the list to include some late additions for the month....

- Pacific Coast Oil Trust (NYSE: ROYT)

- Tupperware (NYSE: TUP)

- Blackstone (NYSE: BX)

Finally tally for our sample of dividend cutters for January 2019: 18 firms, 16 in the oil and gas sector, 1 in the finance sector, and 1 in consumer goods.

References

Seeking Alpha Market Currents. Filtered for Dividends. [Online Database]. Accessed 29 January 2019.

Wall Street Journal. Dividend Declarations. [Online Database]. Accessed 29 January 2019.

Labels: dividends

As best as we can tell, the residential real estate market in the U.S. peaked in March 2018, where since that month, it has declined in 33 of 40 states for which we have recent price and sales data.

That's going by our estimate for the total aggregate value of transactions for existing home sales, which covers somewhere around 87-90% of all home sales in the U.S. economy. Using monthly sales and price data from Zillow, we estimate that this figure has fallen from $129.8 billion in March 2018 to $120.4 billion in November 2018, the last month for which estimates for 40 states and the District of Columbia are covered by Zillow's database is available. That change would mark a decline of 7% nationally.

The following chart shows our estimates of the total aggregate value of transactions for existing home sales for the Top 5 states for this measure from January 2009 through December 2018.

Three of these states marked a peak in March 2018, with the following declines through December 2018's initial estimates: California (-13%), Florida (-7%), and Texas (-13%). New Jersey peaked in April 2018, having since declined by 9% through November 2018, the last month for which its data was available. New York appears to have set a new peak in November 2018, following a shallow dip after having previously peaked in February 2018.

Looking closer at California, the total value of existing home transactions in that state fell from $24.4 billion in March 2018 to $21.6 billion in November 2018, accounting for nearly 30% of the national decline through those months. This large share is mainly attributable to the very large size of California's real estate market. The initial estimate for California's aggregate existing home sales for December 2018 is $21.2 billion.

Getting under the hood for California's existing home sales, Zillow's seasonally adjusted data indicates that the number of sales in the state has been declining since peaking over 43,000 in January 2017, falling to 41,000 in January 2018, and down more significantly to 36,000 through the end of 2018. The seasonally adjusted median sale price of existing homes in the state over that time went from $425,000 in January 2017, up to $471,000 in January 2018, which continued to rise until peaking at $491,000 in November 2018. Compared to 2017, prices were no longer rising fast enough to cover the decline in sales that drove down the aggregate valuation of the state's real estate market in 2018.

The combination of rising prices and falling sales numbers indicates that a relative decrease in the supply of affordable homes is behind the change. Contributing to the increased cost of home ownership in the U.S, particularly after March 2018, was the increase in mortgage interest rates from an average of 3.99% in 2017 to 4.54% in 2018, the highest 30-year conventional mortgage rates have been since 2010. The increase in mortgage rates has been heavily influenced by the Federal Reserve's quantitative tightening policies, where the central bank has been seeking to increase the cost of borrowing for Americans directly by boosting short term interest rates and indirectly by shrinking its holdings of U.S. Treasuries and Mortgage Backed Securities.

On the demand side, other contributing factors may be related to more global concerns, where 2018 saw a considerable slowdown in China's economy. That kind of economic deceleration would reduce the number of Chinese citizens seeking to acquire U.S. real estate, which could represent up to 25% of some local market real estate transactions.

Other states have seen bigger percentage declines in sales than California and Texas, where Zillow's data identifies the real estate markets of Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Illinois, Louisiana, North Dakota, Oregon, and Washington as heavily hit.

Elsewhere on the Interwebs

- Housing Bear Who Called 2018 Slowdown Says Worst Yet to Come

- Americans stopped buying homes in 2018, mortgage lenders are getting crushed, and an economic storm could be brewing

- Bank Of America Calls It: "The Peak In Home Sales Has Been Reached; Housing No Longer A Tailwind" (September 2018)

References

Zillow Research. Home Listings and Sales: Median Sale Price, Seasonally Adjusted, State. [CSV Data]. Accessed 25 January 2019.

Zillow Research. Home Listings and Sales: Monthly Home Sales, Number, Seasonally Adjusted, State. [CSV Data]. Accessed 25 January 2019.

Political Calculations. Median and Average New Home Sale Prices. [Online Article]. 18 January 2019.

Labels: economics, real estate

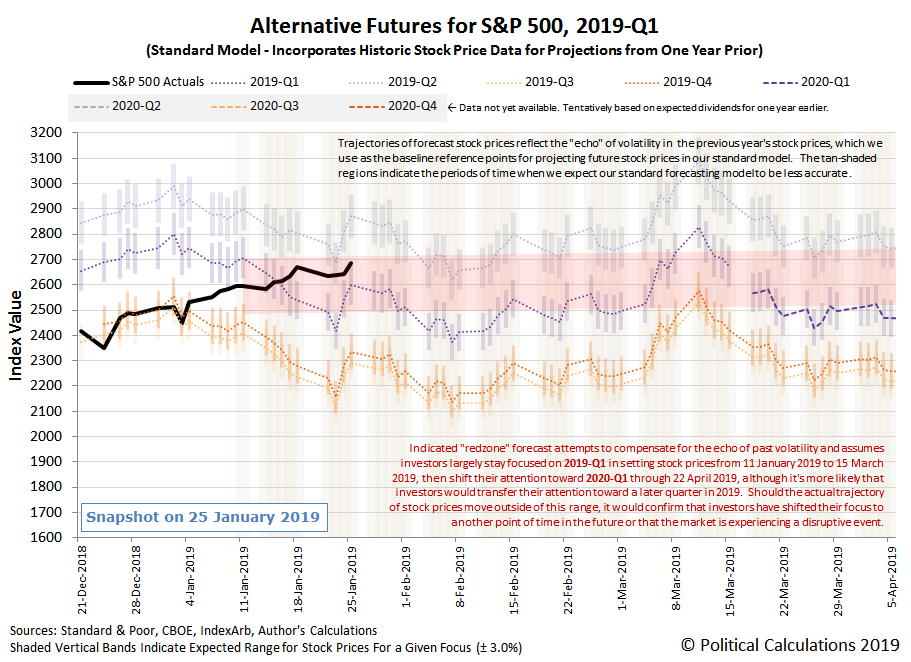

For the S&P 500 (Index: SPX), perhaps the biggest market-moving news of the fourth week of January 2019 came on Friday, 25 January 2019 with the announcement that the latest partial U.S. government shutdown would come to an end. Investors reacted to the news of the end of the 21st federal government shutdown since the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act first set up the modern budget rules the U.S. government follows by bidding up stock prices, with the index rising 0.85% on the day.

In other words, the federal government shutdown was very nearly a complete non-event where investors were concerned. The standard deviation of the daily change in the S&P 500 and its predecessor indices since 3 January 1950 is 0.96%, where the change in stock prices in response to the news the U.S. government would fully reopen is nearly indistinguishable from the market's daily random noise.

It was however enough to move the level of the S&P 500 closer to the top of the redzone forecast range on our spaghetti forecast chart, which if the index rises above that level, would be a signal that something more interesting is happening in the U.S. stock market.

But will it? That will depend upon the random onset of new information that investors learn next week, with the biggest event likely to come on Wednesday, 30 January 2019 when the Fed concludes its next Open Market Committee meeting, when they might provide guidance to investors on what to expect from them with respect to U.S. monetary policies in the upcoming future.

As for what happened last week, there really wasn't much news to influence U.S. stock prices in the holiday-shortened fourth week of January 2019.

- Tuesday, 22 January 2019

- Oil drops nearly 3 percent on rising supplies, China slowdown

- Bigger trouble developing in China:

- China's 2018 growth slows to 28 year low, more stimulus seen

- China's growth slowed by service, farm sectors, despite construction rebound

- China's record 2018 oil, gas imports may be cresting wave as industry slows down

- China state planner warns economic pressure will hit job market

- U.S. home sales hit three-year low, prices rise slowly

- Wall Street drops as economic outlook, corporate forecasts sour

- Wednesday, 23 January 2019

- Thursday, 24 January 2019

- Friday, 25 January 2019

- Oil climbs on Venezuelan crisis despite surging U.S. supply

- Bigger trouble developing in China:

- China to step up economic stimulus in slowdown fight

- Factbox: China rolls out fiscal, monetary stimulus to spur economy

- Trouble developing in Eurozone: As dismal data flows, ECB policymakers promise caution

- Fed Officials Weigh Earlier-Than-Expected End to Bond Portfolio Runoff

- Wall Street advances on Washington temporary shutdown deal

Looking to get a bigger picture of the week's events? Barry Ritholtz summarized the positives and negatives from the week's markets and economy-related news.

As seen on Reddit....

Math problem from r/funny

The answer is 5.099 feet per second, or if you want to reference a more precise mathematical representation for the answer, they are moving apart at exactly √26 feet per second. Assuming, of course, that they're moving on a flat plane, which means we're neglecting the curvature of the Earth's surface in calculating their relative separation speed.

Labels: math, none really

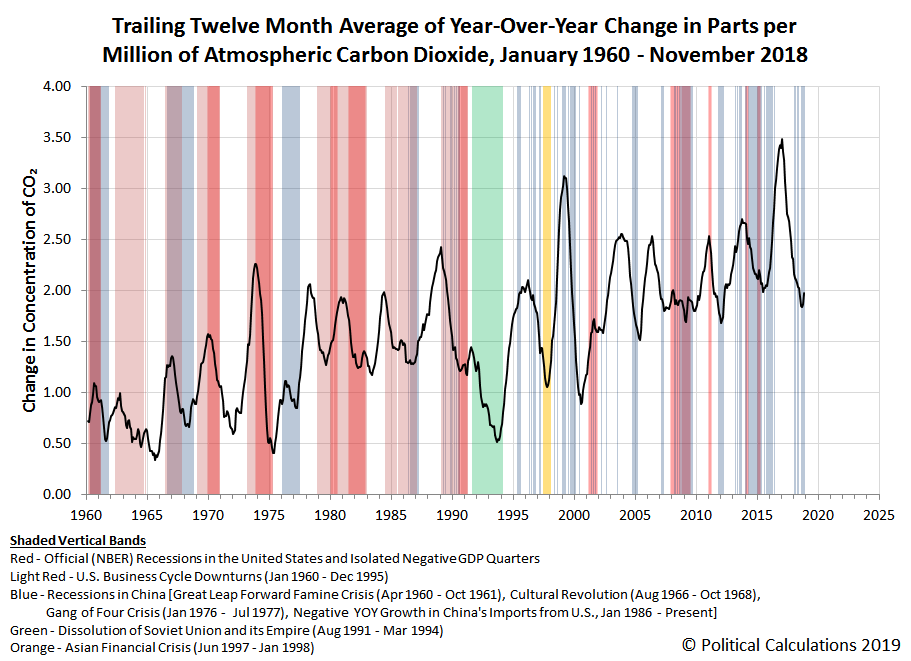

It has been a while since we last visited the NOAA's atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration data, which we're interested in as a unique indicator of the relative health of the Earth's global economy. The following chart illustrates the trailing twelve month average of year-over-year changes in the level of CO2 from January 1960 through November 2018, the last month for which the data is available at this writing.

Following the very strong El Nino event of 2015-2016, which spurred a spike in atmospheric carbon dioxide levels well into 2017, the rate at which CO2 is increasing in the Earth's air has plunged to levels last seen during the Great Recession from 2008 through 2009 and during a subsequent global economic slowdown in 2011-2012, which was particularly notable in China, the world's largest national emitter of carbon dioxide, whose economy has shown signs of another significant slowdown in 2018.

For its part, the world's second-largest national emitter of carbon dioxide, the United States, whose total emissions are a little over half of China's, likely experienced a year-over-year increase in its total CO2 output.

America’s carbon dioxide emissions rose by 3.4 percent in 2018, the biggest increase in eight years, according to a preliminary estimate published Tuesday.

Strikingly, the sharp uptick in emissions occurred even as a near-record number of coal plants around the United States retired last year, illustrating how difficult it could be for the country to make further progress on climate change in the years to come, particularly as the Trump administration pushes to roll back federal regulations that limit greenhouse gas emissions.

The estimate, by the research firm Rhodium Group, pointed to a stark reversal. Fossil fuel emissions in the United States have fallen significantly since 2005 and declined each of the previous three years, in part because of a boom in cheap natural gas and renewable energy, which have been rapidly displacing dirtier coal-fired power.

Yet even a steep drop in coal use last year wasn’t enough to offset rising emissions in other parts of the economy. Some of that increase was weather-related: A relatively cold winter led to a spike in the use of oil and gas for heating in areas like New England.

But, just as important, as the United States economy grew at a strong pace last year, emissions from factories, planes and trucks soared. And there are few policies in place to clean those sectors up.

“The big takeaway for me is that we haven’t yet successfully decoupled U.S. emissions growth from economic growth,” said Trevor Houser, a climate and energy analyst at the Rhodium Group.

Indeed, the lack of such decoupling almost everywhere in the world is why we're able to use atmospheric carbon dioxide data to assess the relative health of the world's economy. Meanwhile, the U.S.' apparent increase in CO2 emissions as its economy has grown in 2018 stands in contrast to the negative economic situation developing elsewhere in the world, which could soon contribute to dragging the U.S. economy down now that the main period of benefit from the stimulus of its December 2017 tax cuts has passed. John Whitehead puts the apparent spike in U.S. carbon dioxide emissions into a longer term context:

The headline is likely an overstatement. Did emissions spike? Emissions in 2018 are still below the pre-Great Recession peak and below several years since the decline began (again, due to the Great Recession). There may be some sort of cyclical pattern here too. In other words, there have been three "spikes" since the peak. The most recent may be related to the 2018 tax cut. As that wears off we might get closer to the Copenhagen Accord target in 2019 and a recession in 2020 might really nail it.

Like it or not, the health of the world's economy will be correlated with atmospheric carbon dioxide levels for quite some time to come.

References

National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. Earth System Research Laboratory. Mauna Loa Observatory CO2 Data. [File Transfer Protocol Text File]. 6 December 2018.

Labels: data visualization, economics

From the end of its 2017 fiscal year to the end of its 2018 fiscal year, the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding increased by $1,271 billion, or $1.3 trillion, to reach a total of $21,516 billion, or $21.5 trillion. Put a little bit differently, the U.S. national debt grew at an average rate of nearly $3.5 billion per day on every day of the government's 2018 fiscal year.

That's a very large number, but 2018 was only the sixth largest annual increase for the U.S. national debt in terms of nominal U.S. dollars. Larger increases were recorded during President Obama's tenure in office in 2012 ($1,276 billion), 2010 ($1,294 billion), 2011 ($1,300 billion), 2009 ($1,413 billion), and 2016 ($1,423 billion).

So it's not an accident that the U.S. national debt has risen to $21.5 trillion, where these six years combined account for 37% of the official U.S. national debt. But to whom does the U.S. government all that money?

The following chart breaks down who the U.S. government's major creditors were at the end of its 2018 fiscal year, which is based on preliminary data that will be revised in upcoming months.

According to the U.S. Treasury Department, the U.S. government spent some $779 billion more than it collected in taxes during its 2017 fiscal year. The difference between this figure and the $1,271 billion that the total national debt officially rose can be attributed to the government's net borrowing to fund things like Federal Direct Student Loans, which have combined to account for over $1.2 trillion of the government's $21.5 trillion debt, or 5.7% of the total public debt outstanding since 2010.

Overall, 71% of the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding is held by U.S. individuals and institutions, while 29% is held by foreign entities. For FY2018, China has retained its position as the top foreign holder of U.S. government-issued debt, with directly accounting for 6.2% between institutions on the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, even though the country has been reducing its holdings of U.S. government-issued debt.

Japan ranks as the second largest foreign holder of the U.S. national debt, with the U.S. owing Japanese institutions 4.8% of its total debt. After that, the European international banking centers of Belgium, Ireland, and Luxembourg combine to account for 3.2% of the U.S. national debt, followed by Brazil at 1.5% and the United Kingdom with 1.3%.

The largest single institution holding U.S. government-issued debt is Social Security's Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which is considered to be an "Intragovernmental" holder of the U.S. national debt, and which holds 13.0% of the nation's total public debt outstanding. The share of the national debt held by Social Security's main trust fund has begun to decline as that government agency cashes out its holdings to pay promised levels of Social Security benefits, where its account is expected to be fully depleted in just 16 years. Under current law, after Social Security's trust fund runs out of money in 2034, all Social Security benefits would be reduced by 23% according to the agency's projections.

The largest single "private" institution that has loaned money to the U.S. government is the U.S. Federal Reserve which, like China, has been reducing its holdings of U.S. government-issued debt. At the end of September 2018, the Fed held just under 11% of the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding. In FY2018, other U.S. institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies have significantly increased their holdings of U.S. government-issued debt as interest rates have risen.

Data Sources

U.S. Treasury. The Debt To the Penny and Who Holds It. [Online Application]. 28 September 2018.

Federal Reserve Statistical Release. H.4.1. Factors Affecting Reserve Balances. Release Date: 26 September 2018. [Online Document].

U.S. Treasury. Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities. Accessed 17 December 2018.

U.S. Treasury. Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government for Fiscal Year 2018 Through September 30, 2018. [PDF Document].

Labels: national debt

The third week of January 2019 saw the S&P 500 (Index: SPX) rise sharply, buoyed by the capitulation of the Fed's interest rate hike-loving hawks and the actions the Chinese government is taking to stimulate its economy.

The following chart shows the trajectory of the S&P 500 during the week that was....

In Week 3 of January 2019, the S&P 500 generally tracked upward within the range indicated by the redzone forecast shown on the chart, which assumes that investors will largely maintain their forward-looking focus on the current quarter of 2019-Q1 through much of the quarter.

But what if that changes? We've already completed one Lévy flight event in 2019, which coincided with investors shifting their attention from the distant future quarters of 2019-Q3/Q4 back to the present quarter of 2019-Q1, so what would it mean if investors collectively refocus their attention toward a different point of time in the future and cause a new Lévy flight event to take place?

The dividend futures-based model we use to develop the alternate futures forecast chart gives us an idea of where the ceiling and the floor for the S&P 500 are at this time, assuming no major changes in expectations for future dividends in 2019 and no market-disrupting noise events.

- If investors shift their focus toward 2019-Q2, the S&P 500 has a potential upside of roughly 7% from where it closed on 18 January 2019, give or take 3%. Based on previous Lévy flight rallies, the rise would most likely be powered by a significant short squeeze.

- If investors instead shift their attention toward 2019-Q3 or 2019-Q4, the S&P 500 could see a relatively rapid 10% decline, again give or take a few percent, in a Lévy flight correction. Should this happen, it would likely come through a cascade of sell orders, enabled by buy orders at much lower stock prices placed as hedging strategies.

- If investors remain focused on the current quarter of 2019-Q1, then stock prices are likely to mostly move sideways, tracking with the redzone forecast indicated on the chart above.

- Finally, there's a fourth option, where investors split their focus between two different points of time in the future, in which case, the level of the S&P 500 will fall somewhere in between the three main alternate future trajectories we've described.

What events could prompt investors to shift their forward-looking focus to any of these points of time? The list could be as long as your imagination, but news events regarding more Chinese government stimulus actions, a trade deal between the U.S. and China, upside surprises for future earnings, et cetera. The random onset of market-moving news events is what gives the stock market its quantum random walk characteristics.

Speaking of which, here are the bigger headlines that we noted for the trading week ending 18 January 2019, where next week's list should be shorter because of the market's closure for the Martin Luther King Day holiday.

- Monday, 14 January 2019

- Oil falls 1 percent on concerns about China slowdown

- Bigger trouble developing in China: GLOBAL MARKETS-China trade shock hits global stocks, commodities

- China's exports shrink most in two years, raising risks to global economy

- China car sales hit reverse for first time since 1990s

- Clarida reinforces Fed's mantra of U.S. policy patience

- China worries weigh on Wall Street, earnings expectations fall

- Tuesday, 15 January 2019

- Oil rises about 3 percent on economic stability hopes

- Bigger trouble developing in China: China signals more stimulus as economic slowdown deepens

- Six regional Fed banks opposed last month's interest rate hike

- Central bank has luxury to wait on rates given muted inflation: Fed's Kaplan

- Fed's Kashkari: Don't snuff out growth with rate hikes

- Fed’s George, often hawkish, says it might be good time for interest-rate pause

- Netflix, China boost Wall Street as investors shrug off Brexit vote

- Wednesday, 16 January 2019

- Oil gains with Wall Street, but rising U.S. fuel stocks weigh

- Bigger trouble developing in China:

- China must prepare for economic difficulties in 2019: premier

- China central bank's record $83 billion injection heightens worries over ailing economy

- Upbeat bank earnings send Wall Street to one-month highs

- PG&E to get pulled out of S&P 500, shares near 2001 lows

- Index change:

- Thursday, 17 January 2019

- Oil slides on increased U.S. output and U.S.-China trade fears

- Bigger trouble developing in China: Job jitters mount as China's factories sputter ahead of Lunar New Year

- Good will bailout? U.S. Treasury Secretary Mnuchin weighs lifting tariffs on China: WSJ

- Fed's Evans says good time for central bank to pause rate hikes

- Wall Street advances as industrials jump on trade hopes

- Friday, 18 January 2019

- Oil jumps 3 percent on OPEC plan details, U.S.-China trade hopes

- Exclusive: U.S. demands regular review of China trade reform

- Explainer: How U.S.-China talks differ from any other trade deal

- China offers to ramp up U.S. imports: Bloomberg

- Fed policymakers leave little doubt: Rate hikes can wait

- Fed's Brainard sees mounting negative risks for U.S. economy

- Fed's Daly leaning toward pause in rate hikes: Washington Post

- Wall Street extends rally on U.S.-China trade optimism

Elsewhere, Barry Ritholtz identified the week's positives and negatives for markets and the economy.

Sharp-eyed readers will recognize that we've adjusted the range of the vertical scale on the alternate futures chart and that the redzone forecast, along with several of the other trajectories, has been angled upward with respect to last week's version. This change has occurred because there was a positive change in the S&P 500's quarterly dividends expected for 2019-Q2, which increased from $14.40 per share to $14.65 per share on 17 January 2019. Let's not forget that the level of stock prices are still primarily driven by basic fundamentals!

There is a remarkably linear relationship between median and average new home sales prices in the United States. The following chart reveals that pattern for annual data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau for new home sales from 1963 through 2017 on a logarithmic scale.

The amazing thing about this relationship is that it has held very consistently even as home prices in the U.S. have experienced both rising and falling trends through these years, where median and average home sale prices have generally increased and decreased in sync with each other. So much so that if we only had the median sale price data for a given period, we could reasonably estimate the average sale price for the same period within 2.7 percent of its recorded value about 68 percent of the time, and within 8.2 percent of its recorded value about 99% of the time.

While the relationship behind this math was developed using new home sales price data, it appears to also hold for existing home sales data with a similar margin of error.

Try it for yourself! Just enter the median new home sales prices for your period of interest in the following tool, and we'll take care of the rest! [If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a working version of the tool on our site.]

For the default data, for a median home sale price of $220,000, we would expect the average home sale price in the U.S. in the same period of time to fall within several percent of $267,100, the value our tool finds after rounding to the nearest $100 increment.

Altogether, the relationship we've now established between median and average home sale prices in the United States enables a particular line of analysis that we've been seeking to do for some time, which hasn't been possible because the relative lack of availability of data for average home sale prices. Which is a strange thing to say because usually when we're looking for data that many reporting agencies don't realize may involve lognormal distributions, it's a lot easier to find averages than it is to get medians. It's a real credit to the outfits that do recognize this pattern in real estate prices that they properly report median sale price data as being representative of the prices that most home buyers are paying, where we hope they come to recognize that mean sale prices provide additional valuable information about these markets that should also be tracked and reported.

References

U.S. Census Bureau. Median and Average Sales Prices of New Homes Sold in United States. [PDF Document]. 23 April 2018. Accessed 12 January 2019.

Labels: math, real estate, tool

John Bogle, the man who made passive, low-cost index investing a real world thing and who, as a result, built Vanguard into one of the world's largest investment management firms, passed away on 16 January 2019 at Age 89.

The idea of index investing that Jack Bogle championed proved to be very a big deal, which is why the index fund made Tim Harford's list of 50 Inventions That Made the Modern Economy (the UK edition is 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy), where we can strongly recommend the 10-minute podcast episode of the related BBC radio series if you want to learn more about its history.

If your available time is shorter than that, Jack Bogle once claimed that he could teach the essentials about investings in just a few minutes. In 2010, the Bogleheads' Ricardo Guerra put him to the challenge, where he distilled a lifetime of learning about successful investing into 3 minutes and 42 seconds....

Back in October 2006, we participated in a chapter-by-chapter review of the original edition of The Bogleheads' Guide to Investing (now in its second edition), where we had the honor of reviewing the final chapter of a book that sought to capture Jack Bogle's wisdom....

That was a lucky break for us, because the final chapter summarized all the lessons presented throughout the book, which gave us the opportunity to further condense Jack Bogle's thoughts on investing into just six lines, although with quite a few links to follow for deeper insights gleaned by the other participants in the project:

- Choose and live a sound financial lifestyle.

- Start to save early, invest regularly and diversify your investments!

- Don't invest in things you don't understand.

- Pay attention to investing costs and especially taxes!

- Plan! Plan! Plan! Plan! Plan! Plan! Plan!

- Avoid fads and master your emotions.

Today, millions of people are considerably richer than they might otherwise have been because of what Jack Bogle wrought. That's one hell of a legacy in the financial world!

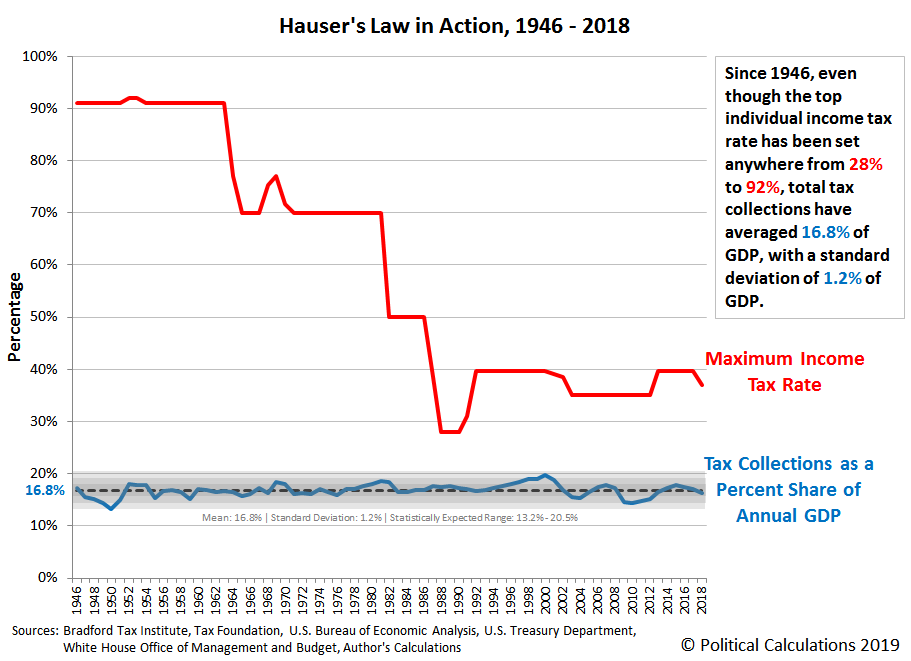

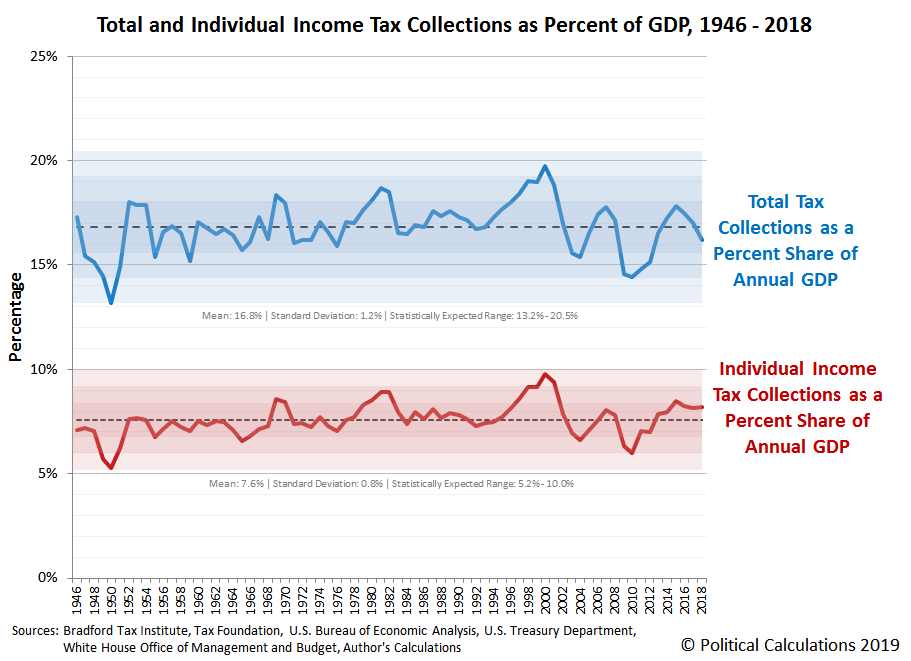

Back in 2009, we wrote about Hauser's Law, which at the time, we described as "one of the stranger phenomenons in economic data". The law itself was proposed by W. Kurt Hauser in 1993, who observed:

No matter what the tax rates have been, in postwar America tax revenues have remained at about 19.5% of GDP.

In 2009, we found total tax collections the U.S. government averaged 17.8% of GDP in the years from 1946 through 2008, with a standard deviation of 1.2% of GDP. Hauser's Law had held up to scrutiny in principal, although the average was less than what Hauser originally documented in 1993 due to the nation's historic GDP having been revised higher during the intervening years.

We're revisiting the question now because some members of the new Democrat party-led majority in the House of Representatives has proposed increasing the nation's top marginal income tax rate up to 70%, nearly doubling today's 37% top federal income tax rate levied upon individuals. Since their stated purpose of increasing income tax rates to higher levels is to provide additional revenue to the U.S. Treasury to fund their "Green New Deal", if Hauser's Law continues to hold, they can expect to have their dreams of dramatically higher tax revenues to fund their political initiatives crushed on the rocks of reality.

Meanwhile, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis completed a comprehensive revision to historic GDP figures in 2013, which significantly altered (increased) past estimates of the size of the nation's Gross Domestic Product.

The following chart shows what we found when we updated our analysis of Hauser's Law in action for the years from 1946 through 2018, where we're using preliminary estimates for the just-completed year's tax collections and GDP to make it as current as possible.

From 1946 through 2018, the top marginal income tax rate has ranged from a high of 92% (1952-1953) to a low of 28% (1988-1990), where in 2018, it has recently decreased from 39.6% to 37% because of the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.

Despite all those changes, we find that the U.S. government's total tax collections have averaged 16.8% of GDP, with a standard deviation of 1.2% of GDP. Applying long-established techniques from the field of statistical process control, that gives us an expected range of 13.2% to 20.5% of GDP for where we should expect to see 99.7% of all the observations for tax collections as a percent share of GDP.

And that's exactly what we do see. The next chart zooms in on the total tax collections as a percent share of GDP data from the first chart, and adds the data for individual income tax collections as a percent share of GDP below it.

What we find is that the federal government's tax collections from both personal income taxes and all sources of tax revenue are remarkably stable over time as a percentage share of annual GDP, regardless of the level to which marginal personal income tax rates have been set. The biggest deviations we see from the mean trend to be associated with severe recessions, when tax collections have tended to decline somewhat more than the nation's GDP during periods of economic distress.

We also confirm that the variation in total and personal income tax receipts over time is well described by a normal distribution. We calculate that personal income tax collections as a percentage share of GDP from 1946 through 2018 has a mean of 7.6%, with a standard deviation of 0.8%.

For both levels of tax collections, if Hauser's Law holds, we would then expect any given year's tax collections as a percent of GDP to fall within one standard deviation of the mean 68% of the time, within two standard deviations 95% of the time, and within three standard deviations 99.7% of the time. And that is pretty close to what we observe with the reported data from 1946 through 2018.

As for high tax revenue aspirations, we can find only three periods where tax collections rose more than one standard deviation above the mean level.

- In 1968, the Democratic U.S. Congress and President Lyndon Johnson passed a 10% income surtax that took effect in mid-year, which suddenly raised the top tax rate from 70% to 77% (which increased the amount collected from top income tax earners by 10%.) Coupled with a spike in inflation, for which personal income taxes were not adjusted to compensate, this tax hike led to outsize income tax collections in that year.

- The sustained high inflation of 1978 (7.62%), 1979 (11.22%), 1980 (13.58%) and 1981 (10.35%) led to higher tax collections through bracket creep, as income tax brackets in the U.S. were not adjusted for inflation until 1985 as part of President Ronald Reagan's first term Economic Recovery Tax Act.

- Beginning in April 1997, the Dot Com Stock Market Bubble minted a large number of new millionaires as investors swarmed to participate in Internet and "tech" company initial public offerings or private capital ventures, which in turn, inflated personal income tax collections. Unfortunately, like the vaporware produced by many of the companies that sprang up to exploit the investor buying frenzy, the illusion of prosperity could not be sustained and tax collections crashed with the incomes of the Internet titans in the bursting of the bubble, leading to the recession that followed.

Now, what about those other taxes? Zubin Jelveh looked at the data back in 2008 and found that as corporate income taxes have declined over time, social insurance taxes (the payroll taxes collected to support Social Security and Medicare) have increased to sustain the margin between personal income tax receipts and total tax receipts. This makes sense given the matching taxes paid by employers to these programs, as these taxes have largely offset a good portion of corporate income taxes as a source of tax revenue from U.S. businesses. We also note that federal excise taxes have risen from 1946 through the present, which also has contributed to filling the gap and keeping the overall level of tax receipts as a percentage share of GDP stable over time.

Looking at the preliminary data for 2018, which saw both personal and corporate income tax rates decline with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, we see that total tax receipts as a percent of GDP dipped below the mean, but still falls within one standard deviation of it, just as in over two-thirds of previous years. Tax receipts from individual income taxes however rose slightly, despite the income tax cuts that took effect in 2018, staying above the mean but still falling within one standard deviation of it.

Hauser's Law appears to have held up surprisingly well over time.

Will it continue? Only time will tell, but given what we've observed, it would take more than simple changes in marginal income tax rates to boost the U.S. government's tax revenues above the historical range that characterizes the strange phenomenon that is Hauser's law.

References

Bradford Tax Institute. History of Federal Income Tax Rates: 1913-2019. [Online Text]. Accessed 13 January 2019.

Tax Foundation. Federal Individual Income Tax Rates History. [PDF Document]. 17 October 2013.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. September 2018 Monthly Treasury Statement. [PDF Document]. 17 October 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. National income and Product Accounts Tables. Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product. [Online Database]. Last Revised: 21 December 2018. Accessed: 14 January 2019.

U.S. White House Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the United States Government. Historical Tables. Table 1.1. Summary of Receipts, Outlays, and Surpluses or Deficits (-): 1789-2023. Table 2.1. Receipts by Source: 1934-2023. [PDF Document]. 12 February 2018.

Labels: data visualization, quality, taxes

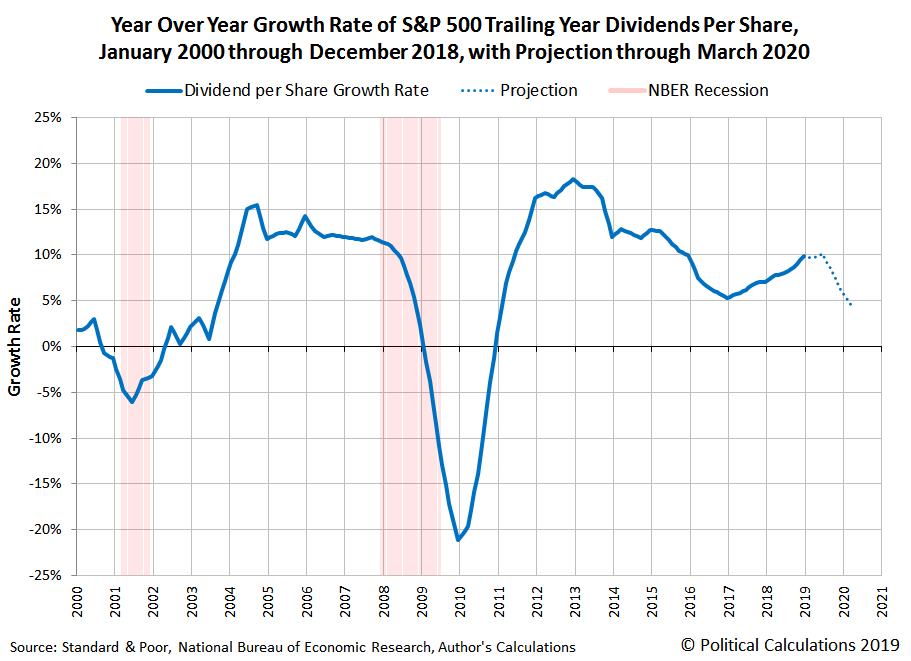

One of the most important and perhaps least well known metrics for the U.S. stock market is the growth rate of dividends for the S&P 500, which is why we started a new series to feature it last year.

The following chart visualizes the year over year growth rate of the S&P 500's trailing year dividends per share for each month of the 21st Century, starting from the beginning of the last year of the 20th Century and continuing through December 2018, with a bonus projection of the currently expected future for S&P 500 dividend growth through March 2020.

We've also indicated the National Bureau of Economic Research's official periods of recession in the 21st Century (so far!) on the chart.

As for how to best use this data, you really want to pay close attention to how fast the growth rate of dividends per share is changing, where negative accelerations for dividends generally coincide with falling stock prices, and positive accelerations tend to coincide with rising stock prices. Also, if you compare the projected future for 2018 with what actually happened for the S&P 500's dividend growth rate, 2018 was a year that mostly lived up to early expectations.

That's not always the case, where we've seen dramatic changes in those expectations in this century, particularly when the U.S. economy fell into recession. If there's one observation that you want to take away from the chart however, it is perhaps Tadas Viskanta's observation that "recessions are a dividend killer"!

Previously on Political Calculations

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.