After discovering that it is now possible to calculate a consumption-based national dividend as originally proposed by Irving Fisher back in The Nature of Capital and Income back in 1906 (also available as a PDF document), we thought we'd next look at how our results for the U.S. from 1984 through 2013 compare to the Gross Domestic Product over that time.

To do that, we've taken our data for the average annual expenditures reported by the BLS and Census Bureau through the Consumer Expenditure Survey and multiplied those figures by the reported number of "consumer units" in the nation, which is roughly the equivalent of U.S. households, since such consumer units/households would represent the ultimate consumers in the nation.

Let's go straight to the charts. The first shows our results for the nominal national dividend for all U.S. consumer units/households.

Here, we see that in the nominal aggregate, both the total and true national dividend for American consumer units has increased over time. We also see that rather than follow steady trajectories over time, there is a remarkable chasm in the data for the true national dividend that runs from 2001 through 2007, which corresponds to the evolution of the first U.S. housing bubble, which was fed by an outflow of funds from the U.S. stock market after the inflation of the Dot-Com Stock Market Bubble peaked in 2000.

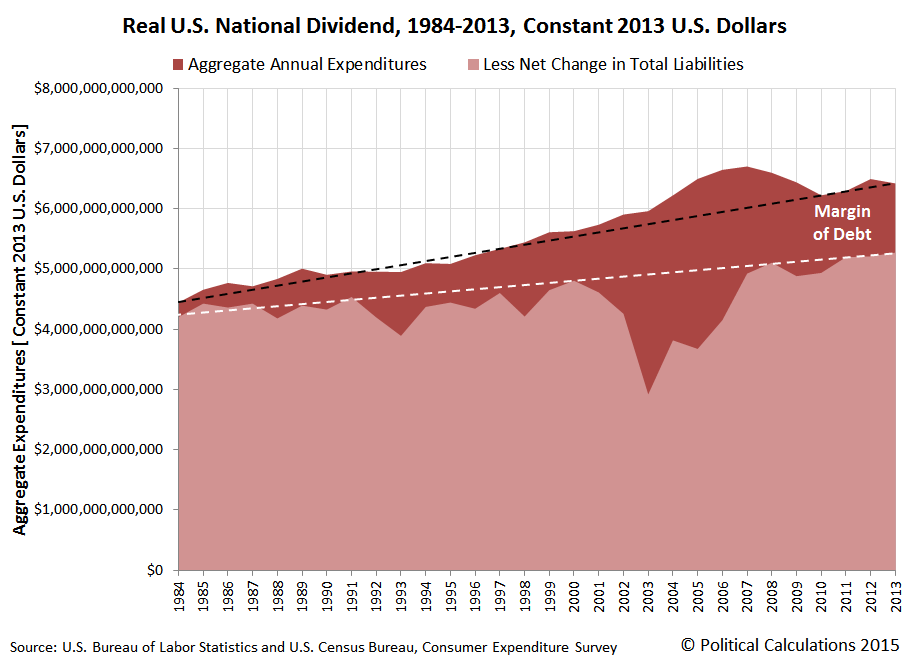

Let's next adjust the data to account for the effects of inflation. Since we're dealing with a measure of the consumption of all American consumer units/households, we've done this math using the CPI-U index.

Unlike what we observed in the trends for the real national dividend per consumer unit, which was characterized by a flat trend for the total national dividend per consumer unit and a falling trend for the household debt adjusted national dividend, we see that there has generally been a rising trend over time for the entire population of American consumers.

What that result suggests is that the real national dividend for the U.S. has increased over time only because its population has increased over time.

In our final chart, we'll calculate the relative percentage share of the national dividend, as measured by the aggregate total of consumer expenditures in the nation, with respect to the nation's GDP. This calculation will give us a sense of how well GDP works as an indicator of the quality of life of U.S. consumer units/households.

What we discover is that over time, GDP has become less and less indicative of the quality of life of American consumer units/households. In 1984, the national dividend in our implementation represented 49% of the nation's GDP, which has since fallen to 38%. What that outcome suggests is that the nation's GDP growth is not diffusing to the benefit of U.S. consumer units/household.

We suspect that has a lot to do with the increasing financialization of the U.S. economy, which is also reflected in the increasing degree to which American consumer units/households are maintaining their real standard of living with increasing levels of debt.

We should also recognize that the downward trajectory in the total national dividend as a percent share of GDP has not been steady over time. The decline of the national dividend has instead occurred in steps, which largely correspond to the terms of different U.S. Presidents, and which would suggest that changes in national policies applied in the Executive branch of the U.S. government are largely responsible for evolution of the trend.

This is where having more historic data would really be useful, but where we are limited because the available data only extends back to 1984. Never-the-less, we do observe that there is a distinct and steady downward trend during the terms of Democratic administrations, while the trend tends to be mostly flat during the terms of Republican administrations. There is one exception, which occurs between 1986 and 1987 during the term of President Reagan, which might perhaps be explained as an outcome of the 1986 Tax Reform Act.

This overall pattern might perhaps be explained by the unusual level of accommodation that Democratic presidential administrations provide to the nation's financial industry and big corporations after being elected with large amounts of funding from these actors, who then gain without sharing any of the benefits they receive to regular American consumer units/households.

That dynamic would then seem to explain why we've see GDP grow over time, without a corresponding improvement in the national dividend for American consumer units/households.

Data Sources

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditure Survey. Total Average Annual Expenditures. 1984-2013. [Online Database]. Accessed 14 March 2015.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index - All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), All Items, All Cities, Non-Seasonally Adjusted. CPI Detailed Report Tables. Table 24. [Online Database]. Accessed 14 March 2015.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. National Income and Product Accounts Tables. Table 1.1.5. Gross Domestic Product. [Online Database]. Accessed 14 March 2015.

Labels: dividends, economics, politics

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.