The aging of the baby boomer generation has always ensured that this day would come, but until yesterday, when the Trustees of Social Security's Old Age and Survivor's Insurance (OASI) Trust Fund and Disability Insurance (DI) Trust Fund released their annual report for 2018, it wasn't supposed to arrive for another two years.

We're referring to the day when the program's administrators would have to begin regularly cashing in the special-issue bonds that they have been steadily accumulating in the trust fund since 1982, just to keep paying out Social Security retirement benefits to America's senior citizens. If they didn't raid the trust fund, under current law, Social Security would have to go back to its default mode of operation where the amount of money that it pays out in benefits cannot exceed the amount of revenue that it collects through the Social Security payroll tax, which would mean benefit cuts for every Social Security beneficiary.

But since there is a trust fund, that day of reckoning for Social Security benefit cuts can be held off for a spell. And by "spell", we mean that it will happen just over 15 years from now, after all of the trust funds's special-issue bonds have been cashed in....

The Social Security program’s costs will exceed its income this year for the first time since 1982, forcing the program to dip into its nearly $3 trillion trust fund to cover benefits.

This is three years sooner than expected a year ago, partly due to lower economic growth projections, according to the latest annual report the trustees of Social Security and Medicare released Tuesday. The program’s income comes from tax revenue and interest from its trust fund.

The trust fund will be depleted in 2034 and Social Security will no longer be able to pay its full scheduled benefits unless Congress takes action to shore up the program’s finances. Without any changes, recipients then would receive only about three-quarters of their scheduled benefits from incoming tax revenues.

Here's the relevant chart from the Trustees' report that shows what will happen after the combined OASI and DI trust funds are depleted in 2034, where all benefits to Social Security recipients at that time will be immediately cut by 21%, which is guaranteed under current law. That's the promise that those who successfully fought Social Security reform nearly a decade ago fought to keep.

What does all this mean for you? Well, if you expect to be alive and count on receiving Social Security benefits in or after 2034, you can reasonably expect that you will only get 79% of the retirement income benefits that is currently indicated that you will receive at the "my Social Security" web site.

What will that mean for the money that you will live on in retirement? You're in luck, because about two weeks ago, we created may be the first retirement planning tool that can take future Social Security cuts caused by the program's trust funds running out of money into account when determining how much you would need to save to support the kind of spending you may plan do in retirement. We've updated the default data to reflect the updated information provided by Social Security's Trustees in their 2018 report. [If you're accessing this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a working version of the tool.]

For the default data, $45,786 is the average amount of annual household expenditures for Americans Age 65 or older in 2016, which comes from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau's annual Consumer Expenditure Survey. Data for 2017 will become available in September 2018.

In recent years, retirement specialists have suggested that an annual withdrawal rate of anywhere from 2.4% to 4.0% of your retirement savings and investments would represent a "safe" rate of withdrawal, where the lower the figure you enter, the more conservative your results will be, which is to say the higher your retirement savings target will become. As a general rule of thumb, the lower you expect the rates of return on your retirement investments to be, the lower the withdrawal rate you should enter.

If you would like to consider the scenario where you would only have retirement income from Social Security, take your Monthly Social Security Retirement Benefit amount and multiply it by 12 in the entry field for "Annual Spending In Retirement" (multiplying the default monthly benefit of $1,850 by 12 is $22,200, which is what you would enter for that case), where the result can be an eye-opening exercise. At the very least, it will give you an idea of what kind of additional savings you would need to build up in your private retirement accounts to compensate for the future cuts to Social Security.

Labels: investing, social security, tool

Did you know that if you're willing to defer collecting retirement benefits from Social Security, you can actually boost the amount of your monthly benefit when you actually do start to collect them?

The percentage by which you might boost your Social Security check can be pretty substantial, which is what our latest tool can help you determine. Just select the age at which you are currently considering to begin taking Social Security benefits and the age to which you might consider putting off collecting them, and we'll tell you how much bigger your monthly benefits check might be as a result.

And it doesn't matter if you're planning to retire early and apply for benefits at Age 62 or are planning to wait until your normal retirement age - if you're planning to retire before you reach Age 70, when you will have to begin taking Social Security benefits no matter what, we can estimate how different your monthly benefits check will be!

If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, click here to access a working version of this tool!

If you want to put that percentage difference into more concrete terms, we encourage you to take advantage of Social Security's retirement benefit estimator to see what that might mean to you in terms of actual dollars.

Just remember that if you will be receiving Social Security benefits after 2032, when all Social Security benefits will be cut after the program's Old Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund runs out of money, you will need to multiply your result by 0.77 (or 77%) to reflect how much of your monthly benefit will remain after the promised cuts take place.

References

Shoven, John. Efficient Retirement Design. Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research. [PDF Document]. March 2013.

Labels: social security, tool

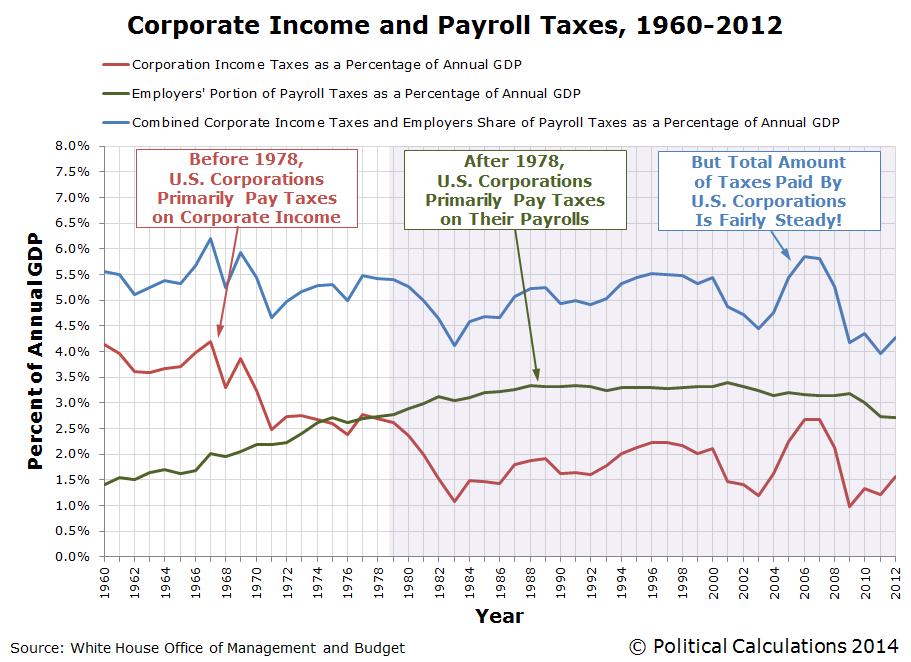

Correlation doesn't prove causation, but make of the following charts what you will. Our first chart shows how much U.S. businesses have paid in both payroll employment taxes and the corporate income tax as a percentage share of GDP in each year from 1960 through 2012 (now corrected to show through 2012 - the original version through 2010 is here):

This chart shows that the total amount of taxes paid by businesses to the U.S. federal government has remained fairly steady as a percentage share of GDP from 1960 through 2012, but the composition of the taxes they pay has changed over time. Before 1978, U.S. businesses paid more in corporate income taxes than in payroll taxes, but since 1978, they have consistently paid considerably more in the form of payroll taxes.

The reason why that changed after 1978 was a series of increases in the employer's portion of Social Security payroll taxes, which were offset by reductions in corporate income taxes. During that time, employers went from having their payrolls taxed at a rate of less than 5% before 1978 to be increased in steps every several years to reach a much higher rate of 6.2% beginning in 1990, where it has held level since. Social Security's tax rates were increased during these years to ensure that the program would remain solvent.

What kind of effect do you think those tax hikes would have had on U.S. businesses, where suddenly, it became a much larger penalty to have lots of people on their payrolls in the United States? And what about those businesses where it really doesn't matter that the jobs be done inside the U.S., like manufacturing?

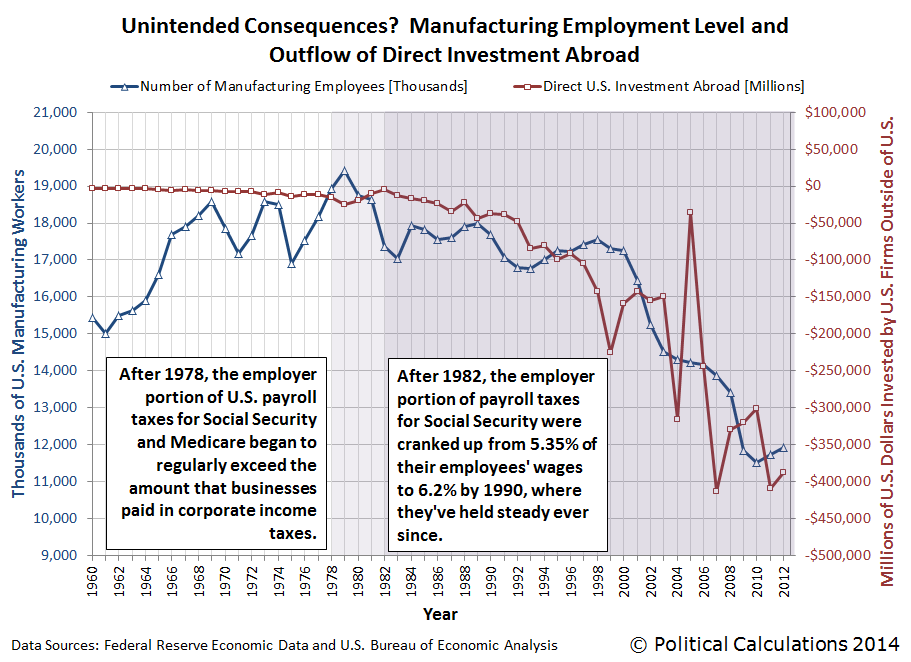

Think about those questions when you consider our next graph:

What we see in this chart is that increases in the amount of money being directly invested by U.S. firms abroad (shown as a negative value on the right hand scale, since it is an outflow for the U.S. economy), largely coincides with and is generally proportional to the change in the number of Americans employed in manufacturing. It's as if U.S. manufacturing firms, in seeking to avoid having to pay higher taxes that would put them at a disadvantage with their competitors by reducing the number of people on their payrolls, shifted their production to be outside of the U.S. as they invested in new production facilities elsewhere in the world.

As a result, the U.S. federal government, in hiking its payroll taxes on U.S. businesses so much, actually drove jobs out of the U.S. instead because it overly penalized employing workers within the U.S. In the process, it lost the tax collections that would have come from those relatively high paying jobs, not to mention potentially lowering the nation's GDP below what it might have been otherwise.

But as they say around the White House these days, since those Americans are no longer trapped in their high-paying manufacturing jobs as they were given the opportunity to pursue their dreams, they're much better off now.

Data Sources

White House Office of Management and Budget. Budget of the U.S. Government, Fiscal Year 2014, Historical Tables. Table 1.2 and 2.1. [PDF Document]. 10 April 2013.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Federal Reserve Economic Data. All Employees: Manufacturing (MANEMP), Thousands, Monthly, Seasonally Adjusted. [Online Database]. Accessed 15 February 2014.

Bureau of Economic Analysis. U.S. International Transactions Accounts Data. Table 1. U.S. International Transactions [Millions of dollars], Line 51. Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 15 February 2014.

Labels: jobs, satire, social security, taxes

Picking up on recent comments by Russ Roberts on the changes in the disability rolls over time, we thought we might revisit Social Security's data on the number of disabled workers collecting disability benefits for the years corresponding to the Great Recession. Beginning with the pre-recession baseline year of 2005, our first chart today shows the number of disabled workers counted as receiving Social Security disability insurance benefits for each year through 2011:

Here, we note that most of the change in the number of disabled workers from year to year is concentrated in older individuals, mostly Age 46 or older. We also note the moving peak of the leading edge of the Baby Boom generation from year to year, which we see shift from Age 58 for 2005 up to Age 64 in Age 2011.

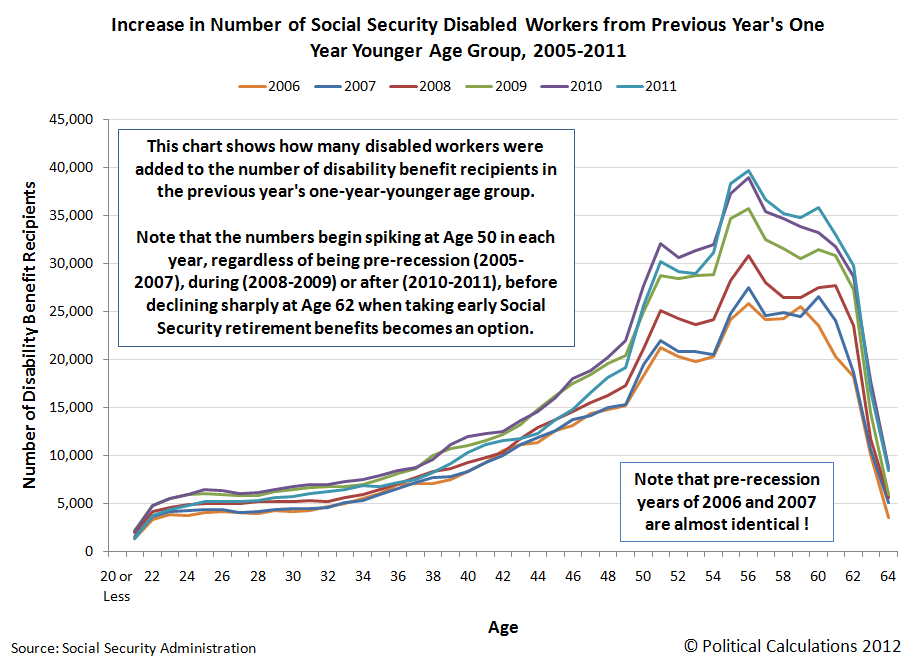

In our next chart, we've extracted the net change in the number of disabled workers receiving Social Security disability insurance benefits from year to year, which we did by subtracting the previous year's number of disabled workers for the one-year-younger age group from the indicated age group:

This chart shows how many disabled workers were added to the number of Social Security disability benefit recipients with respect to the previous year's one-year-younger age group.

Here, we note that there is a distinct spike in disabled workers receiving Social Security disability benefits at Age 50, regardless of each year's economic climate. Here, we earlier found that this corresponds to the Social Security Administration's policy of not seriously challenging the disability claims of workers Age 50 or older.

But perhaps more importantly, in looking at the year-over-year change from 2005 to 2006 (identified as 2006 in the chart) and the year-over-year change from 2006 to 2007 (identified as 2007 in the chart), we find that the year-over-year change for these two pre-recession years are almost identical. This gives us a very good baseline from which we can determine the extent to which the Great Recession has influenced the number of individuals successfully claiming disability benefits in subsequent years.

That result is shown in our third chart, in which we've counted the number of surplus or excess disabled workers added to the number of disability claims in each year from 2007 through 2011 with respect to the net change recorded for each indicated age in 2006:

Adding up the values for each indicated age for each year, we find the number of surplus or excess disabled workers, or rather the number of disabled workers above and beyond what would be considered "normal" and might therefore be attributed to the Great Recession, were added to the disability rolls in the years from 2007 through 2011:

Altogether then, we estimate that some 695,228 individuals, above and beyond the numbers that might be considered to be normal, have filed for and received Social Security disability insurance benefits in response to the Great Recession in the years from 2008 through 2011. We also note that the timing of the increase in the disability rolls would correspond to when many of these individuals would have exhausted their unemployment benefits, suggesting that going on disability became an alternative to seeking gainful employment for these individuals.

And that's a big reason why Social Security's Disability Insurance Trust Fund is now projected to be fully depleted in less than four years time.

Data Sources

Social Security Administration.

Disabled worker beneficiaries in current payment status in December of indicated year, distributed by age and sex. 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011. Accessed 27 August 2012.

Labels: data visualization, insurance, social security

Does it pay to delay taking Social Security benefits?

Let's say you're considering one of three options: taking early retirement at Age 62, retiring at the traditional Age 65, or really holding off on retiring until you've reached Age 70. Which choice might be better for you?

The question matters because people who wait longer before drawing Social Security benefits can draw larger benefits than those who don't wait.

To find the answer, we've tapped Social Security's estimate of the maximum possible Social Security benefits that would be paid for individuals choosing to begin receiving payments in the first month after they've reached each of these ages in January 2012.

We then projected the accumulated total amount of benefits each individual would receive all the way out to Age 100.

But since most Americans won't live quite that long, we also projected how much longer a typical American can expect to live once they've reached the age at which they begin receiving Social Security benefits.

We've presented our results in the following chart, where we've used a solid line to indicate the portion of benefits that would be accumulated based upon a typical American's likely remaining life expectancy, and a dashed line to cover the period from that age all the way out to Age 100.

What we find is that based upon the typical life expectancy for most Americans, it does indeed pay to wait longer to draw Social Security benefits after becoming eligible.

For example, an individual who waits until the traditional Age 65 to begin receiving Social Security benefits will accumulate more money from the program than an individual who begins drawing benefits at Age 62 by the time both have reached Age 77. Since most Americans who reach either age can expect to live into their 80s, they would do better to wait than to take early retirement.

Likewise, by the time an individual reaches Age 82, they will have accumulated more benefits from Social Security by having waited to start receiving them at Age 70 than they will have by beginning to take them at Age 65.

There are two big wild cards in all this however. First is the major unknown of how long you will actually live - if you knew that, then you would know exactly which option might be better for your situation.

That's also complicated by whether or not you have a spouse. In that case, your Social Security benefits would continue to be paid to them in the form of survivor's benefits throughout the rest of their lives, which matters because they might live long beyond your years. That factor would argue in favor of waiting.

The second big wild card however is whether you have another source of income that can carry you from Age 62 through Age 70. Whether that's from regular retirement income that you set aside throughout your working years or from a job, both of which might be at the mercy of the economy, you might find it necessary to begin drawing benefits long before you would otherwise have chosen to do so in an ideal world.

Labels: personal finance, social security

What kind of return can you expect to get from your "investment" in Social Security?

We thought it was long past time to update our previous look at that question to take advantage of the updated actuarial projections that were just issued in July 2010.

We then created a mathematical model for the data that represents the "present law" assumptions for the program's payout, which should put most of the calculated internal rates of return in our tool below within 0.2% of the projected return provided by Social Security's actuaries. That is, assuming they don't hike your taxes or slash your benefits at some point in the future!

Update: Minor calculation glitch now fixed!

High, Low and Average

If your birth year is before 1930, you can expect that your effective rate of return on your "investment" in Social Security is at the high end of the range presented above.

On the other hand, if your average lifetime annual income is high (more than $60,000), you can expect that the approximation is overstating your rate of return and that your effective rate of return is closer to the low end of the approximated range.

Otherwise, you should be pretty comfortably somewhere near the average approximate value!

Winners and Losers, Generally Speaking

In using the tool, you'll find that Single Males fare the worse, followed by Single Females and Two-Earner Couples, while One-Earner Couples come out with the best rate of return from their "investment" in Social Security.

These outcomes are largely driven by the difference in typical lifespans between men and women. For the typical One-Earner Couple, the household's income earner, usually male, dies much earlier than their spouse, who keeps receiving Social Security retirement benefits until they die. This advantage largely disappears if both members of the household work, which increases the amount of Social Security taxes paid without increasing the benefit received.

The Older The Better

Going by birth year, you'll find that those born in recent decades don't come out anywhere near as well as those born back when the program was first launched in the 1930s. This is primarily a result of tax increases over the years, which have significantly reduced the effective rate of return of Social Security as an investment.

Going by birth year, you'll find that those born in recent decades don't come out anywhere near as well as those born back when the program was first launched in the 1930s. This is primarily a result of tax increases over the years, which have significantly reduced the effective rate of return of Social Security as an investment.

For example, when Social Security was first launched, the tax supporting it ran just 1% of a person's paycheck, with their employer required to match the contribution.

Today, 4.2% of a person's paycheck goes to Social Security, down from 6.2% in 2010, which is one reason why Social Security is now regularly running in the red. (President Obama is actively seeking to continue that situation.)

Meanwhile, employers pay an amount equal to 6.2% of the individual's income into the Social Security program. Since benefits are more-or-less calculated using the same formula regardless of when an individual retires, the older worker, who has paid proportionally less into Social Security, comes out ahead of younger workers!

The Poorer the Better

If you play with the income numbers (which realistically fall between $0 and $97,000), you'll see that the lower income earners come out way ahead of high income earners. Social Security's benefits are designed to redistribute income in favor of those with low incomes.

Living and Dying

There's another factor to consider as well. This analysis assumes that you will live to receive Social Security benefits (which you only get if you live!) If you assume the same mortality rates reported by the CDC for 2003, the average American has more than a 1 in 6 chance of dying after they start working at age 19-20 before they retire at age 66-67. Men have a greater than a 1-in-5 chance of dying before they reach retirement age, while women are slightly have slightly over a 1-in-7.5 chance of dying pre-retirement age.

Morbid? Maybe. But your Social Security "investment" isn't as without risk as many politicians would have you believe!

Labels: social security, tool

Assuming you'll live to what the federal government considers to be "full retirement age", you have reasonably good odds of living to Age 84.

The only problem though is that for many of these Americans, the trust funds that support the government benefits upon which they will rely during their retirement years will run out of money during their lifetimes. When that happens, the amount of cash paid out to support these benefit programs will be slashed, as promised by current law.

The benefits in question are those covered by the Social Security Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which provides steady income to retired Americans, the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund, which provides cash for Americans who have disabilities, and Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which covers the cost of hospitalization for retired Americans.

So who will be the Americans most likely to be negatively affected by these trust funds being depleted during their lifetimes?

To find out, we started with the years that Social Security's Trustees estimate that each of these trust funds will no longer have enough money to pay out to Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries, and worked backwards to identify the birth years for people who will be between the ages of 67 and 84 when that happens, which we identified on our chart below:

Here, a majority of people born before the birth year indicated on the left of the blue bar for each trust fund can live to Age 84 without seeing their Social Security or Medicare benefits decreased during their lifetimes.

Meanwhile, people born after the birth year indicated on the right of the blue bar won't necessarily have to worry as much about their Social Security and Medicare benefits being cut, because they'll never receive the generous amount of benefits that individuals born in earlier years received during their lifetimes.

But the blue bar itself indicates the real danger years for Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries. People born between these years will very likely start receiving the really generous benefits supported by the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, but will see those benefits dramatically decline during the part of their lives during which they will rely upon them most.

Just as today's politicians have promised!

Labels: demographics, health care, social security

A proposal to abolish the tax breaks that investors in 401(k) retirement plans receive is being actively considered by members of the leadership of the U.S. House of Representatives:

House Education and Labor Committee Chairman George Miller, D-California, and Rep. Jim McDermott, D-Washington, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support, are looking at redirecting those tax breaks to a new system of guaranteed retirement accounts to which all workers would be obliged to contribute.

The proposal would affect over 47 million active participants and some 14 million retired participants in 401(k) plans who, as of the end of 2005, held over 2.44 trillion U.S. dollars in assets in these defined contribution retirement plans. These numbers do not include the millions who invest in the similar 403(b) type defined contribution plans who work for non-profits or government agencies, whom we do not yet know may be affected, nor those who invest through Individual Retirement Accounts or other tax-deferred plans.

The new system would remove the tax incentives to encourage participants to participate in these kinds of retirement savings plans in favor of compelling all workers in the private sector to "invest" 5 percent of their pay in a "guaranteed retirement account" administered by Social Security. Teresa Ghilarducci of the New School for Social Research in New York, who developed the proposal, describes her vision:

Under Ghilarducci’s plan, all workers would receive a $600 annual inflation-adjusted subsidy from the U.S. government but would be required to invest 5 percent of their pay into a guaranteed retirement account administered by the Social Security Administration. The money in turn would be invested in special government bonds that would pay 3 percent a year, adjusted for inflation.

The current system of providing tax breaks on 401(k) contributions and earnings would be eliminated.

“I want to stop the federal subsidy of 401(k)s,” Ghilarducci said in an interview. "401(k)s can continue to exist, but they won’t have the benefit of the subsidy of the tax break."

Under the current 401(k) system, investors are charged relatively high retail fees, Ghilarducci said.

"I want to spend our nation's dollar for retirement security better. Everybody would now be covered" if the plan were adopted, Ghilarducci said.

Putting on our translator's cap, we would describe the proposal as follows: 401(k) plans would be stripped of the tax incentives that make them attractive to individuals to invest to provide for their own future retirement. Forced to give an additional five percent of their income to Social Security, "investors" would have an additional $600 added to their annual totals from taxpayer funds for each of the years they work. The combined annual amount would then be presumed to grow until the individual retires at an average annualized rate of three percent.

Going by our distribution of taxable household income for 2005, that burden would fall most on households earning between $19,550 and $81,750 each year, with the greatest burden falling on those earning between $28,000 and $42,000. Just going up to household incomes of $500,000, the government would expect to increase its revenue collections by over $315 billion1 per year just for the "special government bonds", with 10.9% of that total coming from those households making between $28,000 and $42,000 a year.

By contrast, those households earning between $250,000 and $500,000 per year would account for just 8.5% of total expected government collections under the proposal. The effect of the much larger incomes is offset by the much lower number of households with those incomes.

No mention is made if the "investment" returns would be taxable. As such, no evidence exists to indicate that it would not be taxed in the same manner as either 401(k) distributions, which it would replace for the individuals in retirement, or Social Security income, both of which are subject to income taxes today. We note that income taxes would guarantee that the average effective rate of return for individuals would be below the three percent target.

Second, by requiring all U.S. individuals earning incomes to contribute above and beyond what they already do to support the Social Security program, the government would be able to substantially increase the percentage of debt financing it obtains from domestic sources. The government gains by having this larger, captive source of debt financing to support either new spending programs or to substantially expand existing spending programs.

But wait, that's not all. The assumption that the government would be able to issue "special government bonds" that would pay an inflation-adjusted return of 3% a year is highly suspect. This figure is likely based upon the average government real interest rate since 1870.

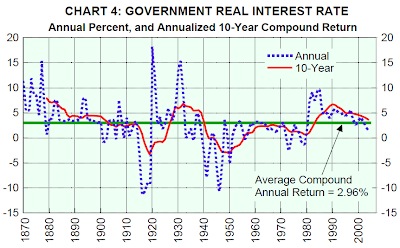

We find that this assumption is faulty in that it assumes that the government can deliver this kind of stable investment performance consistently. The following chart, taken from James A. Girola's Implications of Returns on Treasury Inflation-Indexed Securities for Projections of the Long-Term Real Interest Rate from March, 2006, puts the lie to that assumption:

Since 1870, we see that the real interest rate that the government delivers to investors over time, while averaging 2.96%, is really very volatile. What's more, we observe a correlation with inflation in which above average "performance" largely coincides with periods of high deflation in the U.S. (periods often characterized as panics, depressions or simply deflationary), in which the government was often forced to hike the interest rate it paid out just to keep funds coming in to keep operating. Meanwhile, underperformance is characterized by periods of high inflation, which reduces the effective returns that investors see.

In fact, we see periods between 1914-1920, 1940-1951 and during the 1970s where the one-year investment return from these "ultra-safe investments" were frequently negative after accounting for inflation. If we go by the 10-year compound average return, we see that for roughly seven decades of the 20th century, the government consistently delivered anywhere from less to much less than that "target" three percent annual return.

We also note that the typical pre-tax two-to-three percent annual rate of return on these investments is between one-third and one-half of the average annual inflation adjusted rate of return that represents the long-term average for investments made in the S&P 500.

So what would the worst case outcome for investors be if the government could constrain its urge to tax and spend and investors could keep their 401(k) plans as they are today?

Fortunately, we've already answered that question for a stock market meltdown scenario far worse than today's bear market, or for that matter, one that's worse than the worst ever recorded bear market. We may though have to build a new tool for a side-by-side comparison....

In the meantime, the question for today's 401(k) investors is: can you afford to retire on an investment that can only double the value of your long-term contributions just once every 24 to 36 years?

1 Update 9 December 2010: Corrected from $315 trillion - our apologies for miscounting the number of zeroes!....

Labels: economics, investing, politics, social security, taxes

Want to see where Social Security's taxable income cap fits in with household income percentiles over time? We probably should have shown this chart with our post from yesterday discussing how to minimize risk in funding Social Security, but better late than never! The heavy black line in the chart below shows where Social Security's contribution and benefit base would fall, in constant inflation-adjusted 1982-84 U.S. dollars, from 1986 through 2005:

Note that the Social Security taxable income cap lags changes in household adjusted gross income by about a year, which is what you would expect since it's set after the National Average Wage Index is determined for the previous year!

And while we're at it, here's the same chart, but now with the household income data converted to be in constant, inflation-adjusted 2008 U.S. dollars:

Putting numbers to this chart for 2005, the equivalent value of the cap on income that can be taxed by Social Security is $97,742. That's up some 20.3% from 1986's inflation-adjusted level of $81,279! Meanwhile, for 2008, the value of Social Security's contribution and benefit base has been set at $102,000.

For reference, the floor defining the level of income needed to be part of the Top 50% of household incomes in the U.S. is $33,537 for 2005, up 0.2% from the figure of $33,483 for 1986, which underscores our main point of how stable incomes at lower levels are over time, which helps protect Social Security's ability to deliver its benefits at promised levels.

Labels: social security, taxes

When Social Security was launched, the amount of income subject to Social Security taxes was capped to ensure that the program would have a rock solid source of revenue to support the program's beneficiaries. Otherwise, the amount a Social Security recipient might receive each month could vary wildly from year-to-year, driven by volatility in the U.S. economy.

When Social Security was launched, the amount of income subject to Social Security taxes was capped to ensure that the program would have a rock solid source of revenue to support the program's beneficiaries. Otherwise, the amount a Social Security recipient might receive each month could vary wildly from year-to-year, driven by volatility in the U.S. economy.

Since the program was established as a pay-as-you-go system, with every dollar paid in via Social Security's payroll tax being paid out in the form of benefits to its recipients, securing a stable source of funding was essential to guaranteeing that those receiving benefits would receive the full amount of what they had been promised by the U.S. government.

The only way the program's originators could accomplish this task, as we discussed yesterday in asking why Social Security has a cap, was to set the maximum income that could be taxed to support the program well below the level at which volatility in the economy would drastically affect the amount of taxes on individual incomes collected in any given year.

In this post, we'll show you why that technique works, as well as why it may not be such a great idea to eliminate the cap on the amount of income upon which Social Security taxes may be imposed.

Top Income Earners Have the Most Volatile Income Over Time

Since we lack the breakdown of taxable income from the early days of the Social Security program, we'll instead look at the IRS data available for the years from 1986 through 2005.

We'll visualize this spreadsheet data to first show how the level of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) for households, adjusted for inflation (in constant 1982-84 U.S. dollars), has changed for households in the Top 50%, the Top 25%, the Top 10%, the Top 5% and the Top 1% over this period:

Right off, we see that the inflation-adjusted incomes of U.S. households is the most volatile for those at the top of the income-earning spectrum, while it is the most stable for those at the low end. For instance, if we look at the years coinciding with the peak of the Dot-Com stock market bubble in 2000 through its burst and the following recession in 2002, we see that the incomes of the Top 1% of all income-earning households plummeted some 12.8% from its peak in 2000. We also see that the incomes of the U.S.' top income earners stayed depressed through 2003 and 2004, before recovering to the levels of 2000 in 2005.

Meanwhile, we see that the drop-offs for these years at lower levels of income are much less drastic. Running the numbers, we find that between 2000 to 2002, the adjusted gross incomes at the level defining the threshold of those in the Top 5% declined 5.6%, while the income threshold for the Top 10% fell some 3.7%, the Top 25% threshold dropped 2.2% and the Top 50% dipped just 0.9%.

Clearly, the volatility in income generated from year to year is most volatile for those at the top. Simultaneously, we confirm that the incomes of those at the low end are the most stable over time.

Volatility Levels Across All Incomes

Our next chart stacks these adjusted gross incomes on top of one another, which allows us to see what the overall impact of this top-end volatility would be to the Social Security program:

Taken together, we see that the total level of adjusted gross income plunged by some 8.9% between 2000 and 2002, marking the largest, sharpest drop in the years for which we have data.

What Would This Mean for Social Security?

If there were no cap upon the amount of income that could be taxed to support Social Security today, the amount of taxes on income collected to support the program would have dropped by this 8.9% figure between 2000 and 2002. That, in turn, would affect the program's long term ability to pay benefits in the future.

Right now, as a result of reforms undertaken in the 1980s to prepare for the large scale retirement of the Baby Boom generation, Social Security takes in far more money than it pays out in the form of benefits. The excess funds taken in through the Social Security program's payroll income taxes is directed to its trust fund.

However, in less than ten years, as the Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, Social Security's trust fund will begin running annual deficits, as the amount Social Security must pay out in benefits will exceed the amount it takes in through payroll income taxes.

Worse, once Social Security's trust fund is depleted and it reverts fully back to a "pay-as-you-go" program in 2041 (as currently projected by the program's professional actuaries), that kind of drop in funding for the program would fully translate into a major cut in the benefits paid out to all Social Security recipients.

Note: That kind of cut in benefits paid out would be on top of the 26% reduction in benefits that will occur when the Social Security trust fund is fully depleted, even if no recession or other economic event occurs between now and then that would drastically reduces the payroll tax collections that support the program!

We'll note that there are studies that suggest that eliminating the Social Security taxable income cap would extend the amount of time that Social Security's trust fund be able to operate without deficits by seven years. That would delay the date of reckoning for Social Security recipients by a similar amount of time.

Projecting ahead, we figure that anyone born after 1960 could very reasonably expect to be affected by such recession-period benefit cuts, on top of the large cuts in benefits stemming from the depletion of Social Security's trust fund by the baby boomers, as a direct consequence of the greater level of volatility in payroll tax collections that would result from eliminating Social Security's income cap.

By contrast, since the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes at present falls roughly in line with today's Top 10% income threshold, capping the amount of income that could be taxed at this level would result in a 2.6% cut in benefits paid out to Social Security recipients during trying economic times.

And if the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes were reduced to be back in line with the level of income setting the threshold for the Top 25% of household incomes, just a bit ahead of where this level was set back in 1986, the size of the cut in Social Security benefits in a similar period of recession would be just 1.8%.

We therefore find that the cap on the amount of income that can be taxed to support Social Security protects the ability of the program to provide benefits at the level it promises, especially in recessionary periods.

Now, let's make this personal. If you plan to rely on Social Security benefits to support your household in whole or in part in your retirement years, how big of a cut in your benefits could you afford to take if the U.S. economy turned sour for several years?

Why increase your risk in retirement?

Previously on Political Calculations

- Why Does Social Security Have a Cap? - the first part to this second part!

- Approximating Social Security's Rate of Return - our tool for finding what rate of return you can expect to realize from your "investment" in Social Security.

- Slashing Social Security Benefits - How much of your "promised" benefits will be left when the Social Security trust fund runs out of money? Our tool provides the answers you need to plan now.

Update 23 April 2008: We made minor corrections the chart showing the household adjusted gross income floors from 1986 through 2005. No, the income floors shown shouldn't have been in "billions" of 1982-84 chained U.S. dollars!

Labels: social security, taxes

As of 2008, payroll taxes on income to fund Social Security in the U.S. are limited to the first $102,000 of an individual's annual taxable earnings. According to the Social Security Administration, that's up $4,500 from the limit of $97,500 just the year before and up a total of $60,000 since 1986, just 22 years ago.

As of 2008, payroll taxes on income to fund Social Security in the U.S. are limited to the first $102,000 of an individual's annual taxable earnings. According to the Social Security Administration, that's up $4,500 from the limit of $97,500 just the year before and up a total of $60,000 since 1986, just 22 years ago.

With that big of a dollar increase over such a relatively short period of time, a good question to ask is "why does Social Security even have a cap on the amount of an individual's income that can be taxed?" After all, the cap on the amount of an individual's income that can be subjected to Social Security taxes has existed from the very beginning of the program.

It's often cited that the U.S. Social Security program's originators intended set the maximum taxable wage base to limit the amount of benefits that those earning more than this amount might receive. The Heritage Foundation's Rea S.Hederman, Jr, Tracy L. Foertsch and Kirk A. Johnson make this point in looking at the potential negative impact upon removing the income cap back in 2005 (emphasis ours):

It's often cited that the U.S. Social Security program's originators intended set the maximum taxable wage base to limit the amount of benefits that those earning more than this amount might receive. The Heritage Foundation's Rea S.Hederman, Jr, Tracy L. Foertsch and Kirk A. Johnson make this point in looking at the potential negative impact upon removing the income cap back in 2005 (emphasis ours):

Social Security was created as a pay-related retirement system, not as a welfare program that redistributes money from workers to those in need regardless of whether or not its recipients had paid into the system. The benefits that retirees received were linked to the taxes that they had paid when in the workforce. Social Security was intended to supplement rather than replace private sources of retirement income by providing only a basic, government-guaranteed source of income.

Maximum Level of Benefits and Maximum Taxable Wages. Within this context, Congress determined that it was appropriate to set an upper limit on the amount of income that Americans could receive from the Social Security program. A limit on benefits, combined with the principle that workers' benefits should relate to the amount of money that they paid into the system, made an upper limit on the taxes that workers would pay appropriate.

However, this explanation of why the Social Security tax cap exists falls short in our view. As amended in 1939 prior to making its first monthly payments, the program would pay out in benefits each year the amount that the program had collected through dedicated payroll taxes each year in a "pay-as-you-go" system. Why bother limiting the payouts for those who had paid the most? Why limit the taxes paid to support the Social Security program?

We find that the real answer perhaps lies in the economic environment of the Great Depression and the experience the government had obtained in collecting income taxes, after the 16th amendment to the U.S. Constitution permitted the federal government to impose them.

After taking effect in 1913, the federal income tax soon proved to be a highly effective means of providing funding for the U.S. federal government. In fact, the new income tax was so successful that it more than compensated for the tax collections lost when the government enacted the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the sale of alcohol in the United States, which took effect in 1920.

So successful, in fact, that the new national income tax may have enabled the ability of the government to enact Prohibition in the U.S., as Don Boudreaux has argued:

Prior to the creation in 1913 of the national income tax, about a third of Uncle Sam's annual revenue came from liquor taxes. (The bulk of Uncle Sam's revenues came from customs duties.) Not so after 1913. Especially after the income tax surprised politicians during World War I with its incredible ability to rake in tax revenue, the importance of liquor taxation fell precipitously.

By 1920, the income tax supplied two-thirds of Uncle Sam's revenues and nine times more revenue than was then supplied by liquor taxes and customs duties combined. In research that I did with University of Michigan law professor Adam Pritchard, we found that bulging income-tax revenues made it possible for Congress finally to give in to the decades-old movement for alcohol prohibition.

Before the income tax, Congress effectively ignored such calls because to prohibit alcohol sales then would have hit Congress hard in the place it guards most zealously: its purse. But once a new and much more intoxicating source of revenue was discovered, the cost to politicians of pandering to the puritans and other anti-liquor lobbies dramatically fell.

But that boom in revenues all came before the years of the Great Depression. Don Boudreaux describes the environment that motivated the repeal of Prohibition:

Despite pleas throughout the 1920s by journalist H.L. Mencken and a tiny handful of other sensible people to end Prohibition, Congress gave no hint that it would repeal this folly. Prohibition appeared to be here to stay -- until income-tax revenues nose-dived in the early 1930s.

From 1930 to 1931, income-tax revenues fell by 15 percent.

In 1932 they fell another 37 percent; 1932 income-tax revenues were 46 percent lower than just two years earlier. And by 1933 they were fully 60 percent lower than in 1930.

With no end of the Depression in sight, Washington got anxious for a substitute source of revenue.

That source was liquor sales.

While the federal government turned to taxing liquor sales once more to support its basic operations, the originators of Social Security could not help but be aware of the issue of funding the program, upon which recipients would become partially dependent in supporting themselves, using a new tax on individual incomes. How would they escape the volatility inherent in income tax collections from year to year?

The only way to guarantee that the Social Security program would be able to meet its promised obligations to its beneficiaries would be to remove the element of extreme volatility from its income tax dependent revenue source. And the only way to do that would be to set a statutory limit on the amount of income that could be taxed, and set that limit well below the income levels that were the most volatile from year to year: those of the highest income earners.

The only way to guarantee that the Social Security program would be able to meet its promised obligations to its beneficiaries would be to remove the element of extreme volatility from its income tax dependent revenue source. And the only way to do that would be to set a statutory limit on the amount of income that could be taxed, and set that limit well below the income levels that were the most volatile from year to year: those of the highest income earners.

With this cap on the amount of income that could be taxed in place and the amount of benefits that it would pay out linked to it, Social Security would be capable of weathering the extreme storms in the U.S. economy and ensure that beneficiaries would always receive the level of benefits they had been promised.

That's why Social Security limits the amount of income that can be taxed to support the program. Tomorrow, we'll show you why that cap still makes sense today.

Labels: social security, taxes

Warren Meyer over at The Coyote Blog has been playing with the numbers from his annual Social Security report, and he isn't pleased with what he's estimated to be the effective rate of return on his "investment" in Social Security.

We thought that kind of math might make for a neat project, so we've gone to Social Security's actuarial notes and mined the data to create our tool below, which will approximate what Social Security estimates will be your rate of return on the amount of money you will pay into Social Security over your lifetime. That is, assuming they don't hike your taxes or slash your benefits!

Update 25 August 2011: Before you go any farther, we've made an updated version of this tool available, which incorporates Social Security's actuarial projections as of July 2010! If you're game, we suggest comparing your results here with those from the updated version!

High, Low and Average

If your birth year is before 1930, you can expect that your effective rate of return on your "investment" in Social Security is at the high end of the range presented above.

On the other hand, if your average lifetime annual income is high (more than $60,000), you can expect that the approximation is overstating your rate of return and that your effective rate of return is closer to the low end of the approximated range.

Otherwise, you should be pretty comfortably somewhere near the average approximate value!

Winners and Losers, Generally Speaking

In using the tool, you'll find that Single Males fare the worse, followed by Single Females and Two-Earner Couples, while One-Earner Couples come out with the best rate of return from their "investment" in Social Security.

These outcomes are largely driven by the difference in typical lifespans between men and women. For the typical One-Earner Couple, the household's income earner, usually male, dies much earlier than their spouse, who keeps receiving Social Security retirement benefits until they die. This advantage largely disappears if both members of the household work, which increases the amount of Social Security taxes paid without increasing the benefit received.

The Older The Better

Going by birth year, you'll find that those born in recent decades don't come out anywhere near as well as those born back when the program was first launched in the 1930s. This is primarily a result of tax increases over the years, which have significantly reduced the effective rate of return of Social Security as an investment.

Going by birth year, you'll find that those born in recent decades don't come out anywhere near as well as those born back when the program was first launched in the 1930s. This is primarily a result of tax increases over the years, which have significantly reduced the effective rate of return of Social Security as an investment.

For example, when Social Security was first launched, the tax supporting it ran just 1% of a person's paycheck, with their employer required to match the contribution. Today, 6.4% of a person's paycheck goes to Social Security, again with their employer paying an additional 6.4% into the fund as well. Since benefits are more-or-less calculated using the same formula regardless of when an individual retires, the older worker, who has paid proportionally less into Social Security, comes out ahead of younger workers!

The Poorer the Better

If you play with the income numbers (which realistically fall between $0 and $97,000), you'll see that the lower income earners come out way ahead of high income earners. Social Security's benefits are designed to redistribute income in favor of those with low incomes.

Living and Dying

There's another factor to consider as well. This analysis assumes that you will live to receive Social Security benefits (which you only get if you live!) If you assume the same mortality rates reported by the CDC for 2003, the average American has more than a 1 in 6 chance of dying after they start working at age 19-20 before they retire at age 66-67. Men have a greater than a 1-in-5 chance of dying before they reach retirement age, while women are slightly have slightly over a 1-in-7.5 chance of dying pre-retirement age.

Morbid? Maybe. But your Social Security "investment" isn't as without risk as many politicians would have you believe!

Labels: investing, social security, tool

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.

![2018 Social Security Trustees Report Figure II.D2.—OASDI Income, Cost, and Expenditures as Percentages of Taxable Payroll [Under Intermediate Assumptions] 2018 Social Security Trustees Report Figure II.D2.—OASDI Income, Cost, and Expenditures as Percentages of Taxable Payroll [Under Intermediate Assumptions]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhq0h0E1MtpkLwDpMRyCHfN9f2G96tgrs8wAuP3cTgv7E82FATxZ9a0D-LgF63IoXkPyh0JyE6YDLCu_JCkFfxhOYO2ON8O23wmNW0XWuCCKPluSrKJZ6uMIH-1i1i65u1muU1b/s1600/II_project_IID2.jpg)