To what extent have Philadelphia's residents been able to avoid that city's controversial soda tax?

Until recently, that was an open question, where we've had very little available data to provide any solid insight into the answer. But now, thanks to a combination of tax revenue reports from the city and a recently published working paper by John Cawley, David Frisvold, Anna Hill, and David Jones, we can reasonably estimate how much tax avoidance behavior is occurring within the city.

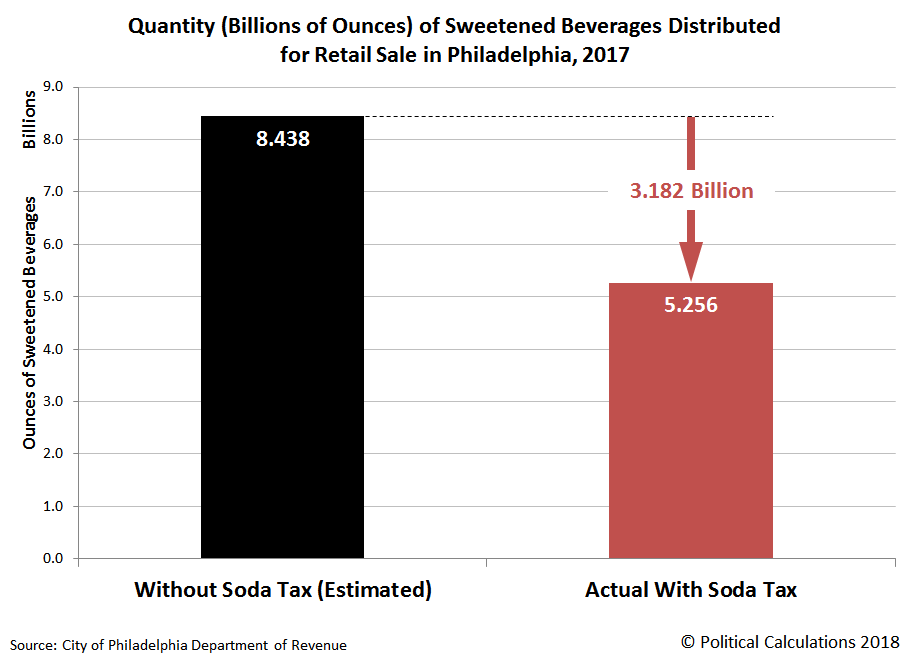

To set the stage, we've already estimated the number of ounces of sweetened beverages have declined as a result of the tax based upon its tax revenue data and the city's estimates of both how much annual revenue it expected to collect from the tax and how much city officials believed the volume of soda sales would decline as a result of their successfully imposing the tax, finding a total reduction of 3.182 billion ounces of beverages subject to the tax occurred during the 2017 calendar year.

Since the city's 1.5 cent-per-ounce sweetened beverage tax was imposed on both regular and diet drinks distributed for retail sale in Philadelphia, we assumed that 25% of this amount was made up of low-to-no calorie diet beverages, the same percentage share that diet drinks made up of all soda sales in the U.S. in 2016. We then assumed that the remaining 75% of the reduction in the quantity of taxed beverages in the city had an average caloric level of 11.7 calories per ounce, about the same as a can of Coca-Cola, to approximate how many calories the tax would have eliminated from the caloric intake of Philadelphians during the year.

For Philadelphia's 2017 population of 1,580,863 people, that works out to be a reduction of 17,612 calories per year, or rather, a reduction of 48.3 calories per day, which would be realized if, and only if, Philadelphians did not substitute other calorie-laden beverages or foods for the beverages subjected to the tax that they avoided purchasing in the city because of the tax.

How realistic that outcome would be hinges on the extent to which Philadelphia consumers engaged in strategies to avoid paying the PBT. This is where the National Bureau of Economic Research working paper provides essential information telling us the extent to which they were successful. Here is a key excerpt from the paper's findings.

Overall, we find that the estimates of the impact of the tax on the consumption of added sugars from SSBs and the frequency of consuming all taxed beverages are negative but not statistically significant for children and adults. Additionally, the point estimates are modest in size. For children, the estimate for added sugars is a decrease of 2.4 grams per day, which is a decrease of 12.5 percent. A gram of added sugars is 4 calories, so this estimate implies a decrease of only 9.6 calories per day or roughly 0.6 percent of the daily recommended caloric intake. For adults, the estimate of a decrease of 5.9 grams of added sugars per day translates to a reduction of 23.6 calories per day or roughly 1.2 percent of the recommended 2,000 calories per day; this estimate is not statistically significant once we control for demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. To illustrate the magnitude of the point estimate, Hall et al. (2011) estimate that a sustained reduction in consumption of 10 calories per day leads to an eventual weight loss of 1 pound, with roughly half of the weight loss occurring after one year. Thus, the estimated reduction of 23.6 calories per day by adults implies a long-term reduction of slightly more than 2 pounds.

The following two charts, Figure 1 for adults (left) and Figure 2 for children (right), reveal the reductions in grams of added sugars in the beverages subject to the Philadelphia Beverage Tax for each group by the total number grams of added sugars consumed daily before Philadelphia's soda tax was implemented. As you might imagine, it shows bigger effects for those who had higher levels of pre-tax consumption, but overall, the average impact for Philadelphia's population indicated by our annotations (in red) reveal the statistically small changes involved for both adults and children.

It is important to recognize at this point that the authors' survey was limited to measure changes in the consumption of non-alcoholic beverages, where they sought to establish the extent to which Philadelphia consumers of beverages subject to the tax changed their consumption patterns within this product category. As a result, the study captured the extent to which consumers substituted untaxed non-alcoholic beverages for taxed beverages, regardless of whether these drinks were directly exempted from the tax, as in the case of bottled water, milk or 100% juices, or if consumers chose to avoid the tax by purchasing the drinks subject to it from locations outside of the city's jurisdiction.

Approximately 27.8% of Philadelphia's population is Age 20 or younger, which tells us that there would be a total of 440,078 children in the city. Multiplying this number by the average reduction of 9.6 calories per day for this demographic group suggests that 4,224,749 daily calories were reduced in this portion of the city's population. Meanwhile, the city's adult population of 1,140,785, who consumed 23.6 fewer calories per day on average, would see an aggregate daily reduction of 26,922,521 calories. Combined, that's a daily reduction of 31,147,275 calories, or 19.7 calories per Philadelphia resident per day, the equivalent of a reduction of 4.9 grams of added sugars per person per day.

The difference between the maximum reduction of 48.3 calories per day per resident that would have occurred without any tax avoidance behavior and the estimated 19.7 calories per day per resident that is estimated to have occurred within just the category of non-alcoholic beverages is 28.6 calories per day per resident, which at 59.2%, represents the portion of the total potential reduction in calorie consumption that the city's tax revenue data says occurred, but really didn't because of the tax avoidance strategies that Philadelphians used to get around the unpopular law.

Since this figure is based only on the portion of taxed beverages that contains calories, it represents a low-end estimate for the amount of tax avoidance occurring in Philadelphia. Factoring in the contribution of diet beverages would potentially put the figure as high as 79%, which assumes diet drinks account for 25% of all taxed non-alcoholic beverage sales in the city.

Meanwhile, this outcome does not consider any of the impact of drinking-age adults substituting any alcohol-based beverages for the city's newly taxed soft drinks, whose calorie content would further reduce the estimated reduction of 23.6 calories per adult resident per day for non-alcoholic beverage consumption indicated by the NBER's working paper. Right now, we've only put an upper bound on what that net change might be, which we'll revisit in future weeks to produce a more refined estimate.

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.