Did you know that Americans who don't have health insurance are more than twice as likely to be killed, literally, than those who do have health insurance?

Did you know that Americans who don't have health insurance are more than twice as likely to be killed, literally, than those who do have health insurance?

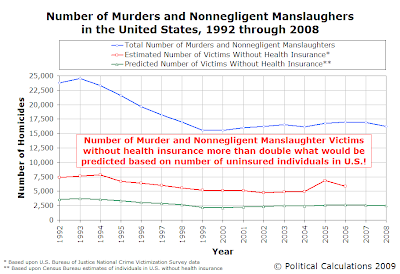

Here's how we know. Starting with the spreadsheet data that the FBI provides for the number of violent crimes and homicides in the U.S. each year, we can combine that information with data collected by the Bureau of Justice Statistics for the percent of victimizations in which the victims had health insurance or were covered by government health programs for its annual survey of Criminal Victimization in the United States (in Table 78). Using these two sources of data, we can work out how many victims of personal crimes of violence had health insurance and how many did not.

Our first graph shows what we found. For the years from 1992 through 2006, the last year for which we have the health insurance status data for violent crime victims, we find that the number of uninsured victims of violent crimes are more than twice as often found to be the victim of a personal crime of violence than the what would be predicted using the U.S. Census' data on the total number of those counted as being without health insurance!

Why does this matter? Well, this finding allows us to debunk some potential junk science related to the current debate on the U.S. health care system

Here, a 2009 study on Health Insurance and Mortality in US Adults by Andrew P. Wilper, Steffie Woolhandler, Karen E. Lasser, Danny McCormick, David H. Bor and David U. Himmelstein offers the following summary:

Objectives. A 1993 study found a 25% higher risk of death among uninsured compared with privately insured adults. We analyzed the relationship between uninsurance and death with more recent data.

Methods. We conducted a survival analysis with data from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. We analyzed participants aged 17 to 64 years to determine whether uninsurance at the time of interview predicted death.

Results. Among all participants, 3.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]=2.5%, 3.7%) died. The hazard ratio for mortality among the uninsured compared with the insured, with adjustment for age and gender only was 1.80 (95% CI=1.44, 2.26). After additional adjustment for race/ethnicity, income, education, self- and physician-rated health status, body mass index, leisure exercise, smoking, and regular alcohol use, the uninsured were more likely to die (hazard ratio=1.40; 95% CI=1.06, 1.84) than those with insurance.

Conclusions. Uninsurance is associated with mortality. The strength of that association appears similar to that from a study that evaluated data from the mid-1980s, despite changes in medical therapeutics and the demography of the uninsured since that time.

Do you see where they likely botched it?

They didn't control for cause of death! Since those without health insurance are estimated to be more likely to die as the result of injuries inflicted by external agents (like murderers), not compensating for that difference will skew the results of this kind of study in a way that suggests that these individuals lack of health insurance is a serious contributing factor to their disproportionately larger share of deaths.

But the last time we checked, things like homicide, while accounting for a portion of the total number of deaths in any given year, are completely independent of whether the affected individual had access to health care or health care insurance.

Through 2007, we know that non-health related causes of death account like these account for 4.2% of the total number of deaths observed in the NHANES III survey population of 33,994 individuals of age two months or older, or 141 out of 3,384 deaths.

Of these, 18 were victims of homicide, 23 died as a result of suicide, 26 died from injuries sustained in falls, and 45 died as a result of motor vehicle accidents.

How much do you want to bet that these factors account for a good portion of the disparity "observed" in the Harvard study?

Considering the Harvard study's population subset of 9004 individuals within the NHANES III survey that ran from 1988 through 1994, 16.2% (2350) were without health insurance. Of the 351 individuals within the group of 9004 who died by the Year 2000 follow up, 17.2% (or roughly 60 individuals) did not have health insurance. Using the 16.2% figure for the entire population and multiplying it by 351, we would predict that 57 individuals without health insurance would have died. This outcome suggests that the Harvard researchers' conclusions are largely based on seeing three more deaths than would be predicted for the uninsured subset of their sample.

How likely is it that these three "extra" deaths might fall into the "non-health related" cause of death category?

Then again, maybe the whole exercise is moot. Since the NHANES III survey is a cross-sectional study rather than a randomized, controlled clinical trial, it's really not possible to draw any real conclusions from findings based on the survey's data. Instead, the best you can get are indications of where future research might be valuable.

And by indicating that the uninsured are 40% more likely than the insured to die, how likely might it be that a team of Harvard researchers will be able to get the funding they need to research it further?

Labels: health care

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.