By most objective measures of its environmental and economic benefits, the Obama's administration's "Cash for Clunkers" program has been a bust. But through all the discussion and debate around the program, it has gone largely unquestioned that the government-subsidized trade in of some 690,114 gas guzzling vehicles in favor of much more fuel efficient vehicles would result in less gasoline being consumed United States.

By most objective measures of its environmental and economic benefits, the Obama's administration's "Cash for Clunkers" program has been a bust. But through all the discussion and debate around the program, it has gone largely unquestioned that the government-subsidized trade in of some 690,114 gas guzzling vehicles in favor of much more fuel efficient vehicles would result in less gasoline being consumed United States.

Until today. Will the Cash for Clunkers program actually reduce the amount of gasoline consumed by Americans?

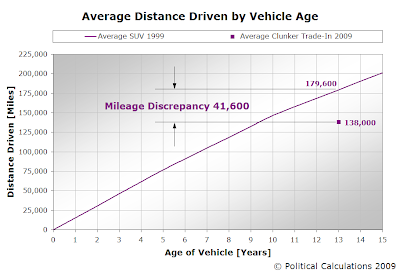

To find out, we first had to establish a baseline for comparison. To do that, we need to identify the basic characteristics of both the typical "clunker" being traded in and the characteristics of the typical brand new replacement vehicle. Here, we found that the typical "clunker" is an 13 year old SUV that gets an average mileage of 16 MPG as is being traded in with an odometer reading of 138,000 miles. The typical replacement vehicle however is a brand new automobile that gets an average miles of 27 MPG.

At first glance, it would seem that the typical new vehicle replacement would indeed consume much fewer gallons of gasoline than the typical clunker. But that assumes that the new vehicle would be driven the same number of miles per year going forward as the clunker was being driven in the years before it was traded in. Is that a realistic assumption?

To answer that question, we next needed to find out how far the typical brand new vehicle replacing the typical old clunker would be driven. We found that basic bit of data posted as the U.S. Department of Energy's Fact of the Week #87, which provided the average annual number of miles by vehicle, by vehicle type and age.

To answer that question, we next needed to find out how far the typical brand new vehicle replacing the typical old clunker would be driven. We found that basic bit of data posted as the U.S. Department of Energy's Fact of the Week #87, which provided the average annual number of miles by vehicle, by vehicle type and age.

What this data indicates is that a brand new automobile in the U.S. would reasonably be expected to be driven 14,319 miles per year, at least for its first five years on the road. That contrasts with the 10,985 miles per year that the average 10-15 year old SUV was driven in 1999. As a result, it would appear that the new vehicle would be driven 3,334 miles more per year.

And that's when we noticed that something wasn't quite adding up right in the numbers we were seeing. The Department of Energy's numbers for 1999 clearly indicate that an average SUV would be driven 15,350 miles per year for its first five years on the road, 13,979 miles per year for its sixth through tenth years on the road, and 10,985 miles per year for years 11 through 15.

But the average odometer reading for a 13 year old clunker in 2009 was 138,400, a discrepancy of 41,600 miles!

That discrepancy confirms that the average 13-year old clunker in 2009 was being driven a lot less than its 1999 counterpart. But why?

Given the improvements in the quality of automotive manufacturing and repair service over time, it didn't make sense that the 13-year old SUV originally produced in 1996 (to become a clunker in 2009) would be driven so much less than an SUV originally produced in 1986. Something else has to account for the discrepancy.

We found that for the 13 years from 1986 to 1999, the price of unleaded gasoline in the U.S. including taxes and adjusted for inflation averaged $1.69 per gallon in constant 2008 U.S. dollars. Meanwhile, between the 13 years from 1996 and 2009, the price of gasoline averaged an inflation-adjusted $2.09 per gallon, a 23.6% increase.

But that's not all. We also found that for the first eight years of driving for 13-year old vehicles in 1999 and 2009, the average price of gasoline was nearly equivalent, at $1.76 for the vehicle hitting the road in 1986 and at $1.73 for the vehicle hitting the road in 1996.

What we found when we factored that into our calculations is that the 13-year old clunker would only be driven an average distance of just 3,863 miles per year.

If we assume that the typical new vehicle replacement then is being driven the same average distance as its 1999 counterpart, that indicates that the vehicle will be driven some 10,456 miles further than the vehicle it is replacing. Dividing the miles driven by the clunker and the new vehicle by their respective mileage figures, we find that the clunker would consume 241 gallons of gas in a year over which it would be driven 3,863 miles, while its new replacement will burn 530 gallons of gas over the 14,319 miles it will be driven.

We therefore find that taking the average clunker off the road will result in an additional 289 gallons of gasoline being consumed by its typical replacement, above and beyond what the clunker itself would consume if it had been left on the road!

Needless to say, we also find that the Cash for Clunkers program to be a bigger bust than was believed before.

Update 15 September 2009: Gavin Andresen e-mails a very good point (from Australia?!):

... I think your analysis of cash for clunkers is wrong.

I suspect that many of the clunkers that were traded in were "second" cars -- driven rarely because their owners have a newer, better "first" car.

The new cars from the cash-for-clunkers program WILL get driven more... but that should be offset because now the old "first car" is the "second car", and will be driven less.

I may be wrong, but my guess (and it's only a guess) is that cash-for-clunkers won't have a statistically significant effect on overall gasoline usage one way or another.

We believe that Gavin is almost absolutely correct (we say "almost absolutely" since there will likely be a small number of single car households that participated in the program.)

Going to Gavin's main point, we agree that the majority of program's transactions came from multiple car-owning households and that the cumulative distance driven for each former clunker-owning household will likely be balanced across several vehicles, as the actual miles driven would be shared among the more fuel efficient cars they own: the new "clunker-replacement" and whatever other vehicles they were already driving in place of their clunker. We also think that in terms of the aggregate statistics, any change in overall gas consumption due to the program for the U.S. will be unnoticeable as it will likely be indistinguishable from noise in the data.

However, as long as politicians continue to champion "reduced gas consumption" or "increased energy independence" as an achievement of the program or a reason to repeat it, we reserve the right to point to our direct clunker-to-new-car replacement analysis!...

Labels: environment

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.