In June 2016, the Earth passed a "grim milestone" with respect to the amount of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere.

The atmosphere has hit a grim milestone — and scientists say we’ll never go back ‘within our lifetimes’

Scientists who measure and forecast the concentrations of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere said Monday that we may have passed a key turning point. Humans walking the Earth today will probably never live to see carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere once again fall below a level of 400 parts per million (ppm), at least when measured at the iconic Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, where the longest global record of CO2 has been compiled.

“Our forecast supports the suggestion that the Mauna Loa record will never again show CO2 concentrations below the symbolic 400 ppm within our lifetimes,” write the researchers, led by Richard Betts of the U.K. Met Office’s Hadley Center, in Nature Climate Change. The study was conducted with colleagues from the Hadley Centre and Ralph Keeling of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography in La Jolla, Calif.

[...]

Concentrations have crossed 400 parts per million on a temporary basis. It began as brief excursions, and last year the annual average concentration at Mauna Loa was more than 400 parts per million for the first time (it was 400.9). Nonetheless, during the course of the yearly cycle in carbon dioxide concentrations, there were still some parts of the year last year when they remained below that level.

What the new study suggests is that those days are over — carbon dioxide will never fall below 400 ppm this year, nor the next, nor the next. The reason is that the strong 2015-2016 El Niño event has pushed concentrations upward more than usual for a given year — El Niños tend to do that, because they dry out tropical regions, lessening tree growth and sparking vast wildfires. That means that even in September of this year, when annual concentrations are typically at their lowest (as northern hemisphere trees lose their leaves and vegetation growth declines heading into winter), they’ll likely still be slightly over 400 parts per million, scientists forecast.

The chart below shows the trend through September 2016, for which the first estimate was reported last week, where it looks like the scientists' projections were slightly conservative.

For what it's worth, the identification of 400 parts per million as a "grim milestone" seems to be more of a psychological event than a meaningful environmental one. Kind of like how the Dow Jones Industrial average has periodically stalled at certain levels from time to time, where ultimately its value continued to grow to exceed them. For instance, that seemed to be the case when the Dow neared 10,000 back in 2009. A year later, the DJI was stuck below 11,000. Today the DJI's value exceeds 18,000.

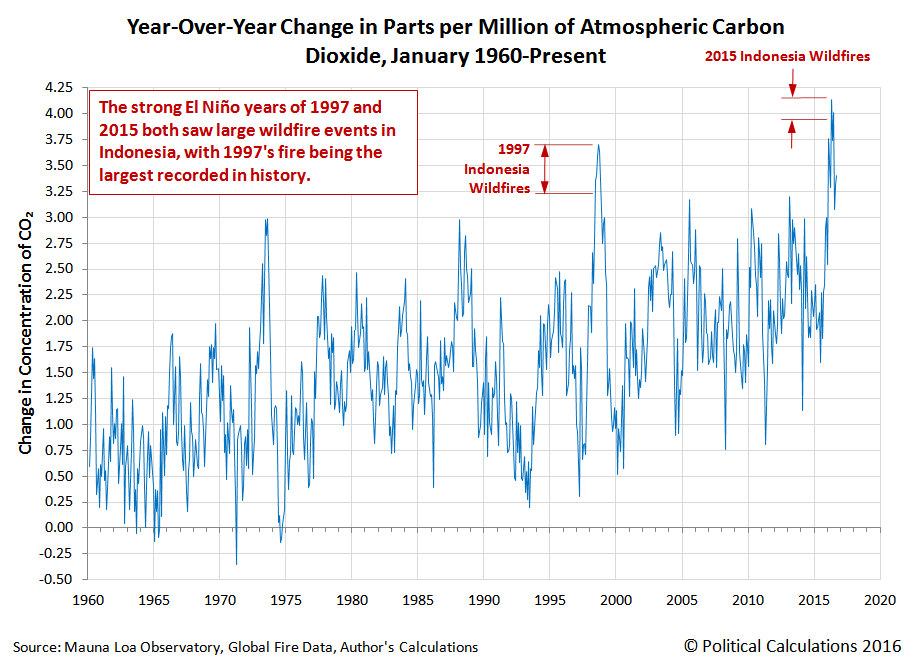

As it happens, we're very familiar with the Mauna Loa Observatory's atmospheric carbon dioxide data, which we have been experimenting with for some time to develop its potential as an indicator of the relative health of the global economy. Or at least we were until large scale wildfires in Indonesia in late 2015 cranked the knob for putting new CO2 into the Earth's atmosphere up to eleven. Or as the chart below illustrates, where it has recently been increasing by more than 4.00 parts per million per year.

Since Indonesia's wildfires have ended, we've been watching the rate at which CO2 in the Earth's atmosphere is being added begin to fall back to more normal levels. We thought it might be interesting to project how much longer that the direct impact of those wildfires would continue showing up in the Mauna Loa Observatory's data, where its presence obscures the contribution of economic activities to atmospheric carbon dioxide levels.

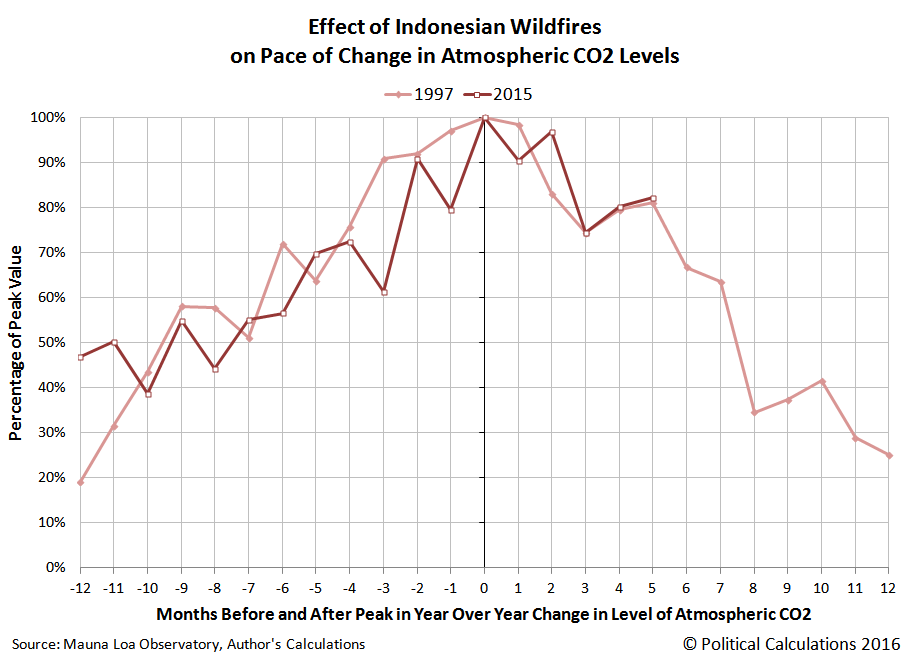

The only problem is that other than 2015's Indonesia wildfires, we only have sufficient data for just one other wildfire event of similar scale to which we can compare it: 1997's Indonesia wildfires, which itself was a much larger event.

We took the year over year change in CO2 levels for those two events and identified the peak point of time at which the Mauna Loa Observatory recorded the maximum rate of addition of carbon dioxide to the Earth's atmosphere that might be attributed to each wildfire. We then defined those respective levels as 100% of the peak wildfire CO2 contribution at that point of time and then calculated the percentage of each wildfire's peak level for the months preceding and following the peak value. The following chart shows those results, where it would appear the pace at which 2015's Indonesia wildfires event is tracking along with what was recorded by its much larger 1997 predecessor.

Based on what we observe in this chart, if the dissipation of CO2 provided by 2015's Indonesia wildfires continues to follow a similar trajectory to 1997's Indonesian wildfires, we should expect the Mauna Loa Observatory's atmospheric carbon dioxide data will be clear of that recent contribution sometime in the next 5 to 7 months.

And that would be the point of time at which we should be able to resume using the MLO's atmospheric carbon dioxide data as an economic indicator!

References

Betts, Richard A., Jones, Chris D., Knight, Jeff R., Keeling, Ralph F. and Kennedy, John J. El Niño and a record CO2 rise. Nature Climate Change 6, 806–810 (2016) doi:10.1038/nclimate3063 Published online 13 June 2016.

Labels: environment

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.