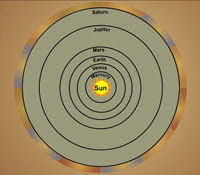

Once, the Earth was held to be at the center of the entire universe. While a strange idea to most people today, it's really not all that hard to understand why. For ancient astronomers viewing the heavens from the Earth, everything, the sun, the moon, the planets and the stars, all appeared to be moving about the Earth in an orderly procession of circular orbits. It made sense because it seemed to describe reality.

Once, the Earth was held to be at the center of the entire universe. While a strange idea to most people today, it's really not all that hard to understand why. For ancient astronomers viewing the heavens from the Earth, everything, the sun, the moon, the planets and the stars, all appeared to be moving about the Earth in an orderly procession of circular orbits. It made sense because it seemed to describe reality.

At least, until they began looking more closely. The movements of two planets, Venus and Mercury in particular, were a particular puzzle as they would, from time to time, stop moving in that orderly procession, go into reverse, stop again, then resume what appeared to be their proper path. And so, to accommodate such discrepancies, the model that ancient astronomers constructed to explain the universe became more complicated. Instead of heavenly bodies simply moving in pure circles about the Earth, they moved in circles within circles. And this model was widely accepted because it was consistent with what came before and seemed to explain reality pretty well.

As more time went by, and as people became better and better at measuring how the sun, moon and planets moved about in the sky, the geocentric model became more and more complicated and elaborate with its circles within circles. A lot of highly intelligent people contributed to the understanding of the motion of the planets and the fact that they were able to describe much of what they saw so well using this model is a testament to their brilliance.

All that changed in 1530 when Nicolas Copernicus (born Mikolaj Kopernik), challenged this prevailing model of the universe with his own observations that suggested that the Sun, and not the Earth, was truly at the center of all the planets and that this heliocentric model was not only much simpler than the elaborately complex geocentric models of his day, it did a much better job at describing the order evident in the sky.

All that changed in 1530 when Nicolas Copernicus (born Mikolaj Kopernik), challenged this prevailing model of the universe with his own observations that suggested that the Sun, and not the Earth, was truly at the center of all the planets and that this heliocentric model was not only much simpler than the elaborately complex geocentric models of his day, it did a much better job at describing the order evident in the sky.

It was controversial, to say the least, as it upended nearly a thousand years of the best thinking of a lot of very smart and powerful people in how they viewed the universe, but as people continued to become better and better at measuring the movement of objects in the sky, and aided by new tools like the telescope that really expanded that ability, ultimately confirmed that the heliocentric model is a much better way to describe the reality we observe.

We're going to do that today with the U.S. stock market.

The Price/Earnings Ratio

The Price-to-Earnings Ratio, or P/E Ratio, is the result of dividing a stock's price per share by its earnings per share. Originally developed by Benjamin Graham and David L. Dodd, the P/E Ratio is the benchmark against which investors measure the performance of the stock market. The following chart follows Graham and Dodd's original formulation of the P/E ratio for the S&P 500 for the period from January 1871 through November 2007, in which the Price per share is the average monthly value of the S&P 500 index and the Earnings per share are taken over a one-year period ending in the month in which the price per share is given (trailing one-year earnings):

The problem with this model of stock market valuation may be seen in the all-time peak value of 46.71 for the P/E ratio that occurred in March 2002. Prior to this time, the P/E Ratio provided a pretty good method of evaluating whether stocks were relatively priced too high or too low compared to the market's long term averages. The extremely high valuations in the Price/Earnings Ratio that coincided with the time of the Dot-com Bubble, which is generally believed to have occurred in the period from 1995 to 2001, would seem to validate that observation. At least, until that inconvenient spike in the P/E Ratio in March of 2002 occurred.

Circles Within Circles

For Robert Shiller, who had famously described the stock market bubble of the late 1990s in his book Irrational Exuberance, that spike in the P/E Ratio in March 2002 is particularly inconvenient as it took place well outside the accepted period of the Dot-com Bubble. So, Shiller adapted the standard model of the P/E Ratio to better reflect that reality by making the original P/E model more elaborate, and more complex.

Building on earlier work with John Campbell, Shiller recalculated the Price-Earnings Ratio for the S&P 500 using the average of annual earnings per share for the index over rolling 10-year periods. Doing so has the effect of smoothing out the volatility of the earnings per share data, while also reducing their value (as corporate earnings have generally and consistently risen over time). The following chart, taken from the New York Times, illustrates the result for the period from January 1881 (recalling that the earnings data covers the period from January 1871 to January 1881) to either June or July 2007:

To further illustrate the increased complexity of this model, we should note that Shiller needed to adjust the earnings per share data to account for inflation in the earnings per share data used to produce the 10-year average. Likewise, Shiller adjusted the price per share data as well (to maintain an apples-to-apples calculation.) These adjustments aren't necessary in the standard P/E Ratio model, as the value of the dollars in which average monthly Price per share and one-year trailing Earnings per share in the period in which they are taken are nearly identical, assuming relatively low changes in the rate of inflation, as has generally been the case in U.S. history.

Why This More Complex Approach Seems to Work Better

Beyond better matching the Dot-com stock market bubble to the period in which it's generally recognized to have taken place, Shiller's method better describes the level of sustainable earnings per share for the companies of the S&P 500. While the one-year trailing earnings show a great deal of volatililty, the averaged inflation-adjusted earnings per share over a ten year period produces much smoother transitions over time.

In fact, Shiller's method is somewhat reminiscent of the method that some boards of directors use in setting their companies' dividends - that of averaging corporate earnings over a number of years, then multiplying by a percentage to get the amount of dividends to be paid out to the companies' shareholders. As we recently discussed, the level at which dividends are set signal what the boards of directors of these publicly traded companies believe to represent the portion of their earnings that they believe to be sustainable in the long term. This may be seen in our chart comparing various measures of corporate earnings against dividends over the last eleven years that we presented earlier this week.

In fact, the rate of growth of cash dividends is the most important factor in setting the overall rate of growth of the stock market. And as we'll soon show, the key to a better benchmark against which to measure stock market performance.

Discovery

We maintain a number of charts illustrating the historic performance of the S&P 500. This first chart shows the S&P 500's index value, or rather, this index' price per share, from January 1871 through November 2007 on a logarithmic scale:

The second chart shows the S&P 500's average monthly one-year trailing dividends per share over the same period, also on a logarithmic scale:

We noticed, in changing views between our copies of these charts in Microsoft Excel, that they seemed to closely correspond. Our next chart superimposes the datas from the two charts together, which confirmed the close correspondence:

This was too good to pass up. So we created a new chart plotting the S&P 500's average monthly price per share against its average trailing one-year dividends per share. The next chart is as we first saw it, in normal scale, connecting the values for each point from earlier to later in time (generally from left to right):

In this chart, which we feel should have the title of being the most remarkable stock market-related chart ever, the stock market bubble of the late 1990's is clearly visible. We can now confirm, with some precision, that the bubble really began in January 1998 when it broke from its previous link to the long term relationship between the S&P 500's price and dividends per share and, in effect, went vertical. The disruptive event which encompasses the meteoric rise of the Dot-com bubble, its peak in August 2000 and subsequent crash, continued until the order that defines the basic relationship between the index' value and its dividends per share re-emerged in June 2003.

The Basic Relationship That Defines the Stock Market

Our next chart illustrates the same data as the previous chart, only using a logarithmic scale for both the S&P 500's average monthly index value and dividends per share, again from January 1871 through November 2007, and incorporates a power function regression trendline that for the entire series of data:

What's especially interesting about this chart isn't the Dot-com bubble of the late 1990s, but the long periods of time in which the relationship between the S&P 500's index value and its dividends per share nearly parallel the long-term trendline. This confirms that there is a very simple mathematical relationship that largely describes the relationship between these two values.

That relationship is given by the following equation:

where the important parts of the equation are P, Price per share, D, Dividends per share and G, which is the ratio of the rate of growth of Price per share to the rate of growth of Dividends per share. A is a constant value.

Update: Digging deeper into the relationship, we found that A is actually not a constant value, but is instead a function of G.

In essence, what the presence of so many straight lines tells us is that for long stretches of time, the ratio of the growth rates of price per share and dividends per share may be treated as a constant during the periods where these lines exist. What's more, the vertical lines that connect these parallel lines represent disruptive events, which punctuate the history of the stock market.

Aside from the Dot-com bubble, which we've already identified, if you look roughly at where the dividends are just under one dollar per share, the vertical line you see there represents the ultimate in disruptive events: the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

These disruptive events, aside from producing relatively rapid changes in the value of stocks, also would seem to have the effect of resetting the conditions under which order emerges in the stock market. After passing through such an event, the growth rate ratio of stock prices to dividends per share reflect the rates at which investors are willing to bid up stock prices in exchange for increases in the companies' dividends, and will do so at a new base price level.

Once established, the price-dividend growth rate ratio may be used as the prime factor for determining whether stocks are appropriately priced with respect to the level of their dividends.

The Long Term Stock Market

Going back to our long-term view of the S&P 500 from January 1871 through November 24, here's the equation that generally describes the S&P 500's longest term relationship between price per share and dividends per share:

With the price dividends growth rate ratio being greater than zero, this relationship indicates that stocks have generally increased in value over time. With the ratio of the growth rate of price per share with respect to the growth rate of dividends per share being greater than one, this relationship indicates that the value that investors have placed on stocks has generally increased faster than the value they can expect to receive in dividends over time.

This makes sense when you consider that the rate of dividend growth reflects only the rate of growth of company earnings that the boards of directors feel can be sustained for the foreseeable future. In addition to this additional earnings component, there are also a number of intangible components that may factor into investor valuations, including the value of the companies' brands, intellectual property, future expectations, etc., all of which add to the typical premium that investors are willing to pay for stocks.

More than this, this premium in the growth rate of stocks compared to the growth rate of dividends explains why dividend yields have decreased over time, and to a lesser extent, why the price earnings ratio itself has tended to increase over time. It's a mathematically inevitable outcome of how investor's have historically valued stocks with respect to dividends (or rather, sustainable earnings.)

The Post Dot-Com Bubble Market

Since order emerged in the stock market following the end of the disruptive event of the Dot-Com Bubble and subsequent crash, we find the relationship between the value of stocks in the S&P 500 and their dividends, presented in the following chart and shown in normal scale, to be:

Simply looking at this chart, the current valuations of the stock market are fully consistent with what we would expect in the post-Dot-com Bubble world, indicating that the value of stocks today is not out of line with the order in the market that has emerged since June 2003.

In the chart, we show the ratio of stock price to be 0.7597 and, being less than 1, this value indicates that in the post-Dot-com Bubble market, investors are requiring greater levels of dividends to justify bidding up the price of stocks than they have historically. From the perspective of market psychology, this also makes sense. Having gone through the Dot-com Bubble's period of inflated valuations, investors are now collectively doing the same thing that banks do with their business loans when credit gets tight - they're requiring higher levels of concrete performance on the part of the businesses to justify making the transactions.

What Will Happen Next

By and large, the market will continue on its current trajectory unless and until another disruptive event occurs. That could be a good thing, such the widespread implementation of computing technology that drove the productivity boom of the mid-1990s, which preceded the actual bubble phase of the stock market, and which we know now former U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan erroneously called "irrational exuberance" at the time. Or it could be a bad thing, as in the case of a market crash.

In any case, when order re-emerges, the price dividend growth rate ratio will set the pace for what investors can expect from the stock market. It will be a brand new day - only now, the sun will be in the center.

What better way to celebrate our third anniversary?

Labels: dividends, earnings, economics, investing, SP 500, stock market

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.