Are you graduating college in 2009 with a bachelor's degree? If so, we can project how much purchasing power you'll lose over the first 25 years of your working life thanks to President Obama's ambitious spending plans, using the tool we've developed for PJTV's Generational Theft contest. Just enter the indicated data in the table below, and we'll run the numbers!

Pretty scary, huh? Unfortunately, these results are based on some of the best economic data we have available today. Here's where it all came from:

1. A 2009 College Graduate's Earnings from 2009 through 2034

1.1 Basic Assumptions

Determining how much a typical 2009 college graduate's income will change over the next 25 years turns out to be pretty easy. First though, we'll need to make a few assumptions about the individuals who receive their bachelor degrees in 2009:

1. The vast majority of this group is between the ages of 18 and 24, with comparatively little work experience compared to older individuals.

2. Most 2009 college graduates will move on to occupations that provide full-time, year-round employment. We will limit our analysis to this particular segment of all employed bachelor degree holders.

3. Data compiled by the U.S. Census in each year's Current Population Survey accurately reflects the mean income earned for persons who have attained bachelor degrees for each age group identified.

4. We will also assume that the typical earnings trajectory indicated by the data from the Current Population Survey for income earned in each year from 1997 through 2007 reflects a pattern that will be shared by 2009 college graduates throughout their careers.

In reality, it's much more likely that the relative incomes of college graduates will continually shift with respect to their peers from year to year, sometimes dramatically as individuals may change jobs or receive promotions as they gain work experience. Taken as a group however, the mean earnings trajectory will define the basic path a random individual selected from the overall population could reasonably expect to see their income change over time.

1.2 Plotting the Typical Earnings Trajectory for College Graduates

Having established the basic assumptions for our earnings trajectory analysis, we next turned to the U.S. Census' Current Population Survey [1] for the years from 1998 through 2008. These reports, issued each March and covering income earned in the period of the previous year, provide the mean income earnings for persons having attained a bachelor's degree, of both sexes and all races, who work full-time, year-round by age group.

We took this data and calculated each age-group's percentage of the average "starting" salary for each of the covered years from 1997 through 2007, which we represented as the mean income earned by individuals in the Age 18-24 group. We next modified the various age-groups to instead represent the number of years elapsed between these groups and the Age 18-24 cohort, which worked out to be five year intervals. Our results are plotted in Figure 1-1:

Figure 1-1. Mean Earnings Trajectories as Percentage of Mean "Starting" (Age 18-24) Salary

In the chart above, the earnings trajectories shown as a percentage of the Age 18-24 individual's "starting" salary for each year fall within a comparatively narrow band, with the extremes marked by years in which the U.S. was in recession (2001) or recovering from recession (2003). In addition to each year's specific earnings trajectory, we also determined the average earnings trajectory for all years. Table 1-1 gives the percentage of the Age 18-24 mean earnings represented by the number of years elapsed since the indicated age group would most likely have graduated from college (by definition, the income of the Age 18-24 group is 100%):

Table 1-1. Average Earnings Trajectory for Bachelor Degree Holders, 1997-2007

| Age Range | 18-24 | 25-29 | 30-34 | 35-39 | 40-44 | 45-49 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years Elapsed Since Graduating | 0 | 5 | 10 | 15 | 20 | 25 |

| Percentage of "Starting" Mean Income | 100% | 139% | 173% | 201% | 210% | 216% |

This average earnings trajectory defines the typical inflation-adjusted income level a bachelor degree holding person working full-time, year-round can expect to earn each year as they progress through their careers. We confirmed this result by finding a close agreement between the average percentages of "starting" income presented above and the percentages of inflation-adjusted mean incomes we obtained for the age groupings of 1997, who we tracked through 2002 (5 years elapsed) and 2007 (10 years elapsed.)

The average earnings trajectory may be used to reasonably project a typical 2009 college graduate's future real income over a 25 year period. We will use the formula representing the earnings trajectory of a typical bachelor degree holder that we obtained through regression analysis of the income data presented in Figure 1 in our analysis.

2. The Burden of President Obama's Debt

2.1 Scope of the Forecast Deficits

When the forty-fourth President of the United States, Barack Obama, assumed office in January 2009, the United States was well into an economic recession that had begun in December 2007 [2]. His predecessor, George W. Bush, a Republican, had joined with the Democratic Party-controlled U.S. Congress in reacting to the declining economic situation by increasing federal spending levels throughout the year, even as receipts from tax collections fell. Consequently, the United States ran a record deficit exceeding $455 billion in President Bush's final full year of the presidency, some $293 billion more than the level of the deficit recorded in 2007 [3] and an all-time record for the deficit in nominal (non-inflation adjusted) terms.

But that was nothing compared to what President Obama would do as he came into office. Seeking to exploit the economic crisis as a means of implementing his party's political agenda and rewarding its supporters with minimal opposition and minimal oversight, President Obama joined with his fellow Democratic Party leaders in the U.S. Congress to initiate even higher levels of federal spending, even as federal tax receipts continued to decline.

That combination of falling tax revenues and highly inflated spending level was brought home graphically by the Washington Post [4], who featured the following graph [4a] comparing the level of the U.S. federal government annual budget deficit during each year of the prior Bush administration and the projected values for 2009 and the following ten years:

Figure 2-1. Actual vs Projected Annual U.S. Budget Deficit, 2000-2019.

The data used to create the chart above is taken from Table 1-1 of the Congressional Budget Office's Baseline and Estimate of the President's Budget [5]. With 2009's anticipated budget deficit expected to quadruple the final full-year record deficit of the Bush administration, and with much higher estimates of future budget deficits than used by the Obama administration, which has since raised its own projections of these deficits [6], we will use this data to measure the impact of President Obama's proposed spending upon the national debt.

2.2 Increasing National Debt Levels Through 2034

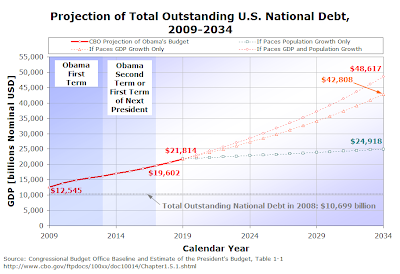

Beginning with the level of the Total Outstanding Debt to the Public recorded by the U.S. Treasury as of December 31, 2008 of $10.699 trillion USD [7], we added the annual deficits projected by the Congressional Budget Office for each year going forward through 2019. After 2019, we projected how the U.S. national debt would grow under several different assumptions: at the rate of U.S. resident population growth, at the nominal (non-inflation adjusted) rate of growth of U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and at the combined rate of growth of both U.S. population and nominal GDP. Figure 2-2 summarizes our results:

Figure 2-2. Projection of Total Outstanding U.S. National Debt, 2009-2034.

As we'll soon confirm, of these three potential rates of growth for the total outstanding debt to the public for the U.S., the combined rate of growth of both population and GDP is consistent with both the Congressional Budget Office's projections and the rate at which the national debt has grown in recent years. We will use this projection in our analysis.

2.3 Projected Economic Growth from 2009 through 2034

For projecting the rate of growth of the U.S. nominal (non-inflation adjusted) Gross Domestic Product from 2009 through 2034, we turned to the recently released projections of GDP growth produced by the Social Security program's Old Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance (OASDI) Trustees [8] for these years. Figure 2-3 displays the OASDI Trustee's projections of nominal GDP based upon the Social Security program's high, intermediate and low cost assumptions.

Figure 2-3. Social Security OASDI Trustees Projections of Nominal GDP, 2009-2034.

The different levels of GDP projected by the OASDI trustees correspond to the actuarial analysis of how different levels of GDP would impact the cost to the Social Security program of making benefit payments. For our purposes, we have consistently utilized the OASDI Trustees' Intermediate Cost Assumptions for projecting the level of GDP into the future.

2.4 Projections of Population Growth from 2009 through 2034

Figure 2-4 provides the U.S. Census Bureau's projections of the level of the U.S. resident population for each year from 2009 through 2034 [9].

Figure 2-4. U.S. Census Projections of Resident Population, 2009-2034.

While we've primarily used the rate of U.S. population growth combined with the rate of nominal GDP growth to project future levels of the U.S. national debt in our analysis, we will also be using the projected population data to measure the relative burden of the U.S. national debt upon individual Americans.

2.5 U.S. Debt and GDP per Capita

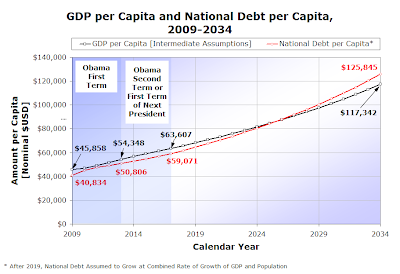

Now that we've presented the projections of the overall national debt, GDP and population for our analysis, we can now determine the per capita figures for our projected data. Figure 2-5 compares the national debt per capita and nominal GDP per capita for the years from 2009 through 2034.

Figure 2-5. GDP per Capital and National Debt per Capita, 2009-2034.

We see that throughout the period from 2009 through 2034, the per capita level of the national debt holds very close to the level of per capita GDP. What this narrow margin suggests is that the U.S. has little room to absorb the potential fiscal shock of a significant event, such as the United States experienced in 1917 with the onset of World War I, in 1941 with the onset of World War II or the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York City.

2.6 The National Debt Burden from 2009 through 2034

Defining the basic debt burden of the United States as the ratio of the total outstanding national public debt to the national income, as measured by nominal GDP, Figure 2-6 illustrates how we project the U.S. basic debt burden will change from 2009 through 2034.

![Figure 2-6. Projected National Debt Burden [Debt-to-Income (GDP) Ratio], 2009-2034](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEifTRrmGECOKdcV7yyD1o6KokQbX_CulHUzuhsHT18ABsAxfDGDP8NRLfuCo9SxanMQJFoXGAF6qiGIYtvPlfFZfGJeUvy_VOQxFLcba1IIAo_ef2IiV7kymR6a0ae_KwuN2Z-L/s400/gtf.PNG)

Figure 2-6. Projected National Debt Burden [Debt-to-Income (GDP) Ratio], 2009-2034.

We see that the level of the debt burden increases dramatically increases from a level of 70.3% in 2008 to nearly 90% in the first year of the Obama administration. Moreover, we see the projected national debt burden increase to 96.5% in the third year of President Obama's first term, before falling to 94.9% in 2013. From here, the national debt burden is projected to fall slightly to 92.2% in 2015 before steadily rising to 107.2% in 2034, given our basic assumptions.

2.7 The National Debt Burden per Capita from 2009 through 2034

The national debt burden per capita, which is also known as the national debt per capita-to-income index [10], provides a means of determining how the national debt burden may be divided among the nation's population[11]. Figure 2-7 shows how this measure is projected to change from 2009 through 2034 based on our assumptions.

Figure 2-7. Projected National Debt Burden per Capita, 2009-2034.

This chart reveals how dramatically the national debt burden for individual American is projected to grow as a result of the Obama administrations' spending programs. We see that the index value is projected to rise from a value of 2.31 in 2008, peak at a value of 3.04 in 2010, before falling to 2.96 in 2013.

From here, the index value gently descends to 2.83 through 2019. After 2019, we see the level hold constant at 2.78, which corresponds to our assumption that the national debt will grow at the combined rate of growth of national GDP and population. We should note that the relatively horizontal portion of the index value from 2014 through 2019 indicates that the CBO's projection of the growth of the national debt during this period largely paces the combined growth rates of nominal GDP and population, which affirms this method of projecting the future value of the national debt in the United States.

3. The Impact of Obama's Debt on Purchasing Power

3.1 The Role of Inflation

The elephant in the room where a 2009 college graduate's future income-based purchasing power is concerned lies in the effect of inflation upon their future earnings. With the United States expected to sharply increase the rate of inflation as a means of paying down its sharply higher debt, how could inflation not have a long term role in determining an individual's purchasing power?

And yet, it won't. At least not in how one would expect it to have an impact.

The reason why goes to how firms have historically reacted to increases in price inflation. We base this assumption on a 1999 paper, "Wage Inflation and Worker Uncertainty" [12] by Mark Schweitzer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, which examines forty years of inflation and compensation data, spanning from January 1957 into October 1997, which includes the hyperinflation period of the late 1970s. Schweitzer, now a vice president at the Cleveland branch of the Federal Reserve, found that:

To examine the relationship between nominal wage growth and inflation, I use an unusually long, detailed time series (including more than 40 years of data) which shows that wages have generally moved with the sum of prices and productivity. Furthermore, this relationship is contemporaneous, at least for annual data.

Consequently, while price-driven inflation can negatively affect purchasing power in the short term, in the long term, an individual's total compensation will adjust in step with both price-driven inflation and changes in productivity, ultimately producing a neutral effect. Schweitzer finds that:

Pay changes are mostly based on compensation at other firms, cost-of-living indexes, and their own firms’ financial results (in that order). This suggests that wages will respond to price changes, with little danger that a burst of worker optimism will set off an inflationary spiral.

We'll simply note that the same outcome applies in the case of worker pessimism.

3.2 Transforming Higher Debt into Higher Taxes

Having established that inflation has, at best, a neutral effect upon the long term purchasing power of an individual, we next considered the most likely result of a higher national debt: higher taxes. Here, we modeled the relationship between the maximum personal income tax rate against the national debt per capita burden, which we introduced in Section 2.7, for the years from 1913 to 2008 [13]. Figure 3-1 illustrates the relationship we found:

Figure 3-1. Top Tax Rate vs National Debt Burden per Capita, 1913-2008.

Using the tool that models this historic relationship, which represents the political equilibrium established by politicians in the U.S. in setting personal income tax rates with respect to the size of the national debt and growth of both GDP and population, we find that with a peak value of 3.04 for the national debt burden per capita reached in 2010 that we would project that the maximum personal income tax rate in the U.S. to rise from 35% in 2009 to roughly 70% within the next several years.

We further believe that with the national debt burden per capita index value expected to be sustained near this level through 2034, that this figure will represent the maximum personal income tax rate for the indefinite future.

3.3 The Reduction of Purchasing Power

We believe the increased level of taxation required to support the higher level of the national debt will have the largest effect upon an individual's purchasing power. While politicians may opt to not raise personal income tax rates to this specific level, they are likely to increase other taxes to make up the difference. We will therefore assume that change in the amount we project that individuals will pay in higher income taxes will fully represent the amount by which individuals can expect their purchasing power to decline.

Using Political Calculations' "Build Your Own Income Tax" tool [14], we calculated the amount of income taxes that a 2009 college graduate with a bachelor's degree might expect to pay through the first 25 years of their career. Table 3-1 reveals our findings (we assume one income earning individual per household, with a single standard tax credit of $2,400 for each. We've arbitrarily set $250,000 as the threshold income to which the maximum personal income tax rate would apply for both the current and projected tax scenarios for the ease of direct comparison.):

Table 3-1. Burden of Increased Taxes to Support Higher National Debt for Average Bachelor Degree Holder.

| Year | Projected Income (Constant U.S. dollars) | Projected Federal Taxes $0 to $8,000........10% $8,000-$30,000...10-25% $30-250,000+.....25-70% | Current Federal Taxes $0 to $8,000........10% $8,000-$30,000...10-25% $30-$250,000+....25-35% | Difference | Percentage Change of Projected Income in Purchasing Power Due to Increased Taxes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | $35,182 | $6,768 | $6,478 | $290 | -0.8% |

| 2014 | $48,762 | $11,662 | $10,206 | $1,455 | -3.0% |

| 2019 | $60,985 | $16,711 | $13,705 | $3,006 | -4.8% |

| 2024 | $70,604 | $21,115 | $16,554 | $4,561 | -6.5% |

| 2029 | $73,993 | $22,727 | $17,578 | $5,149 | -7.0% |

| 2034 | $76,152 | $23,827 | $18,236 | $5,591 | -7.3% |

We find that as 2009's college graduates advance throughout their careers, they can expect that their purchasing power will be reduced in real terms by 6.5 to 7.3% as they enter their peak income earning years some 15 years into their careers, thanks to the additional tax burden needed to support President Obama's increased level of deficit spending today.

Those who graduate into higher-than-average paying occupations requiring greater levels of productivity, such as business/economics, computer science or engineering fields, can expect their real purchasing power to decline by a greater margin than that given by these average figures.

References

[1] U.S. Census. Detailed Income Tabulations from the Current Population Survey, 1998-2008, http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/dinctabs.html. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

Specific Table References:

[1a] 1998: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/031998/perinc/06A_001.htm

[1b] 1999: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/031999/perinc/new06a_001.htm

[1c] 2000: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032000/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1d] 2001: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032001/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1e] 2002: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032002/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1f] 2003: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032003/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1g] 2004: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032004/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1h] 2005: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032005/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1i] 2006: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032006/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1j] 2007: http://pubdb3.census.gov/macro/032007/perinc/new04_001.htm

[1k] 2008: http://www.census.gov/hhes/www/macro/032008/perinc/new04_001.htm

[2] National Bureau of Economic Research. Determination of the December 2007 Peak in Economic Activity. http://www.nber.org/cycles/dec2008.html. December 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[3] Congressional Budget Office Director's Blog. "Monthly Budget Review: FY 2008 Deficit and First 9]TARP Estimate". http://cboblog.cbo.gov/?p=186. November 7, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[4] Washington Post. "Projected Deficits." http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/graphic/2009/03/21/GR2009032100104.html. March 21, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[4a] Image URL: http://media3.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/graphic/2009/03/21/GR2009032100104.gif.

[5] Congressional Budget Office. "A Preliminary Analysis of the President’s Budget and an Update of CBO's Budget and Economic Outlook". http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/100xx/doc10014/Chapter1.5.1.shtml. March 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[6] Lazarro, Joseph. Recession Pushes U.S. Budget Deficit to $1.84 Trillion". Daily Finance. http://www.dailyfinance.com/2009/05/12/recession-pushes-us-budget-deficit-to-1-84-trillion/. May 12, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[7] U.S. Treasury Direct. "Debt to the Penny and Who Holds It". Total Outstanding Debt to the Public, December 31, 2008. http://www.treasurydirect.gov/NP/BPDLogin?application=np. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[8] U.S. Social Security Administration. "2009 OASDI Trustees Report". http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2009/index.html. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[8a] U.S. Social Security Administration. "2009 OASDI Trustees Report". Table VI.F6. - Selected Economic Variables, Calendar Years 2008-85 [GDP and taxable payroll in billions] http://www.ssa.gov/OACT/TR/2009/lr6f6.html

[9] U.S. Census Bureau, "2008 National Population Projections," released August 2008. http://www.census.gov/population/www/projections/2008projections.html. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[9a] U.S. Census Bureau, "2008 National Population Projections: Table 3. Resident Population Projections: 2008 to 2050". http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/tables/09s0003.pdf.

[10] Political Calculations. "Why Isn't The U.S.' National Debt per Capita Higher?" http://politicalcalculations.blogspot.com/2005/12/why-isnt-us-national-debt-per-capita.html. December 30, 2005. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[11] Political Calculations. "The U.S. Economy at Your Fingertips". http://politicalcalculations.blogspot.com/2009/04/us-economy-at-your-fingertips.html. April 8, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[12] Schweitzer, Mark. "Wage Inflation and Worker Uncertainty". Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland. http://www.clevelandfed.org/research/commentary/1997/0815.pdf. August 15, 1997. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[13] Political Calculations. "Transforming Higher Debt Into Higher Taxes". http://politicalcalculations.blogspot.com/2009/04/transforming-higher-debt-into-higher.html. April 15, 2009. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

[14] Political Calculations. "Build Your Own Income Tax!" http://politicalcalculations.blogspot.com/2008/05/build-your-own-income-tax.html. May 29, 2008. Retrieved May 31, 2009.

Update 2 June 2009: We have a short link to this post suitable for texting or twittering!: http://bit.ly/qEzZh

Labels: demographics, gdp, national debt, taxes, tool

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.