A proposal to abolish the tax breaks that investors in 401(k) retirement plans receive is being actively considered by members of the leadership of the U.S. House of Representatives:

House Education and Labor Committee Chairman George Miller, D-California, and Rep. Jim McDermott, D-Washington, chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee’s Subcommittee on Income Security and Family Support, are looking at redirecting those tax breaks to a new system of guaranteed retirement accounts to which all workers would be obliged to contribute.

The proposal would affect over 47 million active participants and some 14 million retired participants in 401(k) plans who, as of the end of 2005, held over 2.44 trillion U.S. dollars in assets in these defined contribution retirement plans. These numbers do not include the millions who invest in the similar 403(b) type defined contribution plans who work for non-profits or government agencies, whom we do not yet know may be affected, nor those who invest through Individual Retirement Accounts or other tax-deferred plans.

The new system would remove the tax incentives to encourage participants to participate in these kinds of retirement savings plans in favor of compelling all workers in the private sector to "invest" 5 percent of their pay in a "guaranteed retirement account" administered by Social Security. Teresa Ghilarducci of the New School for Social Research in New York, who developed the proposal, describes her vision:

Under Ghilarducci’s plan, all workers would receive a $600 annual inflation-adjusted subsidy from the U.S. government but would be required to invest 5 percent of their pay into a guaranteed retirement account administered by the Social Security Administration. The money in turn would be invested in special government bonds that would pay 3 percent a year, adjusted for inflation.

The current system of providing tax breaks on 401(k) contributions and earnings would be eliminated.

“I want to stop the federal subsidy of 401(k)s,” Ghilarducci said in an interview. "401(k)s can continue to exist, but they won’t have the benefit of the subsidy of the tax break."

Under the current 401(k) system, investors are charged relatively high retail fees, Ghilarducci said.

"I want to spend our nation's dollar for retirement security better. Everybody would now be covered" if the plan were adopted, Ghilarducci said.

Putting on our translator's cap, we would describe the proposal as follows: 401(k) plans would be stripped of the tax incentives that make them attractive to individuals to invest to provide for their own future retirement. Forced to give an additional five percent of their income to Social Security, "investors" would have an additional $600 added to their annual totals from taxpayer funds for each of the years they work. The combined annual amount would then be presumed to grow until the individual retires at an average annualized rate of three percent.

Going by our distribution of taxable household income for 2005, that burden would fall most on households earning between $19,550 and $81,750 each year, with the greatest burden falling on those earning between $28,000 and $42,000. Just going up to household incomes of $500,000, the government would expect to increase its revenue collections by over $315 billion1 per year just for the "special government bonds", with 10.9% of that total coming from those households making between $28,000 and $42,000 a year.

By contrast, those households earning between $250,000 and $500,000 per year would account for just 8.5% of total expected government collections under the proposal. The effect of the much larger incomes is offset by the much lower number of households with those incomes.

No mention is made if the "investment" returns would be taxable. As such, no evidence exists to indicate that it would not be taxed in the same manner as either 401(k) distributions, which it would replace for the individuals in retirement, or Social Security income, both of which are subject to income taxes today. We note that income taxes would guarantee that the average effective rate of return for individuals would be below the three percent target.

Second, by requiring all U.S. individuals earning incomes to contribute above and beyond what they already do to support the Social Security program, the government would be able to substantially increase the percentage of debt financing it obtains from domestic sources. The government gains by having this larger, captive source of debt financing to support either new spending programs or to substantially expand existing spending programs.

But wait, that's not all. The assumption that the government would be able to issue "special government bonds" that would pay an inflation-adjusted return of 3% a year is highly suspect. This figure is likely based upon the average government real interest rate since 1870.

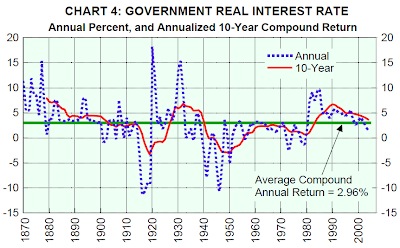

We find that this assumption is faulty in that it assumes that the government can deliver this kind of stable investment performance consistently. The following chart, taken from James A. Girola's Implications of Returns on Treasury Inflation-Indexed Securities for Projections of the Long-Term Real Interest Rate from March, 2006, puts the lie to that assumption:

Since 1870, we see that the real interest rate that the government delivers to investors over time, while averaging 2.96%, is really very volatile. What's more, we observe a correlation with inflation in which above average "performance" largely coincides with periods of high deflation in the U.S. (periods often characterized as panics, depressions or simply deflationary), in which the government was often forced to hike the interest rate it paid out just to keep funds coming in to keep operating. Meanwhile, underperformance is characterized by periods of high inflation, which reduces the effective returns that investors see.

In fact, we see periods between 1914-1920, 1940-1951 and during the 1970s where the one-year investment return from these "ultra-safe investments" were frequently negative after accounting for inflation. If we go by the 10-year compound average return, we see that for roughly seven decades of the 20th century, the government consistently delivered anywhere from less to much less than that "target" three percent annual return.

We also note that the typical pre-tax two-to-three percent annual rate of return on these investments is between one-third and one-half of the average annual inflation adjusted rate of return that represents the long-term average for investments made in the S&P 500.

So what would the worst case outcome for investors be if the government could constrain its urge to tax and spend and investors could keep their 401(k) plans as they are today?

Fortunately, we've already answered that question for a stock market meltdown scenario far worse than today's bear market, or for that matter, one that's worse than the worst ever recorded bear market. We may though have to build a new tool for a side-by-side comparison....

In the meantime, the question for today's 401(k) investors is: can you afford to retire on an investment that can only double the value of your long-term contributions just once every 24 to 36 years?

1 Update 9 December 2010: Corrected from $315 trillion - our apologies for miscounting the number of zeroes!....

Labels: economics, investing, politics, social security, taxes

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.