For most Americans, the coronavirus pandemic has had two dimensions. The first dimension involves the excess deaths per capita recorded during the pandemic. The second dimension involves the direct economic impact from how people and governments responded to the pandemic, which for many, meant job losses.

The analysts of Hamilton Place Strategies came up with a way to visualize both dimensions for all 50 states in a single chart. Here it is!

The chart indicates each state's COVID deaths per capita on the vertical scale, and each state's job loss per capita on the horizontal scale. By showing the national averages for both dimensions, it divides the 50 states into four quadrants.

The lower left hand quadrant is the best one in which to find your state. The states in this sector experienced both low rates of COVID deaths and low levels of job lossses during the pandemic. The best performing states are those that are furthest away from the intersection of the national averages for COVID deaths per capita and job loss per capita, where Idaho, Utah, and West Virginia having the best outcomes (Idaho and Utah with respect to job losses, West Virginia with respect to COVID deaths).

By contrast, the states in the upper right hand quadrant experienced the worst outcomes. Here, the combination of high COVID death tolls and high job losses indicates poor performance. Once again, the states furthest away from the intersection of the national average COVID death toll and job losses are the ones who ranked the worst.

Here, we find four states performing worst than almost all others. Louisiana, New Jersey, Nevada, and New York were the worst performing states in the U.S., with New York having by far the worst outcome of all states for both measures.

States falling in the other two quadrants had mixed outcomes, with high rates of COVID deaths per capita combined with lower than average job losses per capita, or vice versa.

With respect to COVID deaths per capita, Mississippi had the worst outcome in upper left quadrant. For the measure of job loss per capita, Hawaii had the worst performance in the lower right quadrant.

All in all, it's a neat bit of analysis. We wish we had thought to frame the data this way!

Labels: coronavirus, data visualization, unemployment

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics released its Employment Situation report for March 2020 early today, the first monthly report since the coronavirus recession began in mid-March. Here's how it describes the change in non-farm employment since the BLS' February 2020 report:

Total nonfarm payroll employment fell by 701,000 in March, and the unemployment rate rose to 4.4 percent, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reported today. The changes in these measures reflect the effects of the coronavirus (COVID-19) and efforts to contain it. Employment in leisure and hospitality fell by 459,000, mainly in food services and drinking places. Notable declines also occurred in health care and social assistance, professional and business services, retail trade, and construction.

The data from this report was collected via the BLS' monthly survey of business establishments covering pay periods including 12 March 2020, and as such, represents a snapshot in time from just before President Trump declared a national emergency on 13 March 2020 and a week before state governors began ordering residents to stay-at-home and statewide business closures on 19 March 2020.

In the two weeks since then, the number of initial unemployment insurance claims has spiked sharply upward, breaking previous records, with 3.3 million filing new unemployment claims as of 26 March 2020 and another 6.6 million on 2 April 2020.

Those newly unemployed Americans will be showing up on the April 2020 employment situation report, but the bigger question begging to be answered is how high could U.S. unemployment rise in the coronavirus recession?

Back on 22 March 2020, St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank president Jim Bullard estimated the unemployment figure may hit 30% during the second quarter of 2020, but where does that number come from? After all, the unemployment rate in February 2020 was 3.5%, and that would be a huge change.

The St. Louis Fed's Miguel Faria-e-Castro worked through step-by-step how that back of the envelope estimate was calculated. In the following passage, we've added the links to the blog posts he references, other data he cites may be accessed via the Federal Reserve Economic Database (FRED):

- Civilian labor force in February 2020 = 164.5 million (BLS via FRED)

- Unemployment rate in February 2020 = 3.5% (BLS via FRED)

- Unemployed persons in February 2020 = 5.76 million (#1 * #2)

- Workers in occupations with high risk of layoff = 66.8 million (Gascon blog post)

- Workers in high contact-intensive occupations = 27.3 million (Famiglietti/Leibovici/Santacreu blog post)

- Estimated layoffs in second quarter 2020 = 47.05 million (Average of #4 and #5)

- Unemployed persons in second quarter 2020 = 52.81 million (#3 + #6)

- Unemployment rate in second quarter 2020 = 32.1% (#7 / #1)

That's useful back of the envelope math, so we've built the following tool to do it, where you may substitute the values to consider other scenarios, such as state level data or the data for other nations. If you're accessing this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, you may need to click through to our site to access a working version.

Running the tool with the default data, we can see where the St. Louis Fed gets its estimate of potential 32% unemployment. We should caution that this is a ballpark estimate of how high U.S. unemployment may grow, where the tool allows for more refined estimates of the impacted workforce as better information becomes available.

We've also generalized the descriptions for the affected workforce from Faria-e-Castro's description, which should make the tool more generally applicable than the specific scenario he considered.

Looking back at the employment situation in 2020-Q2, with roughly 10 million new unemployment claims filed in the last two weeks just as the quarter began, we are already nearly one fifth of the way to the St. Louis Fed's estimate of potential job losses from the coronavirus recession.

Image credit: James Yarema

Previously on Political Calculations

- How Fast Could China's Coronavirus Spread?

- Estimating Economic Impacts From A Disaster Shock

- Atmospheric CO2 and the Coronavirus

- What Is Your Risk Of Exposure To Coronavirus in A Public Outing?

- Will You Get A Tax Credit Rebate Under the CARES Act?

- Visualizing the Progression of COVID-19 in the United States

- Recapping Political Calculations' Coronavirus Coverage

Labels: coronavirus, forecasting, recession, recession forecast, tool, unemployment

Good morning, White House Staffer!

Say, do you remember when we said you should enjoy it while you can as the average price of gasoline in the U.S. dropped below $3.50 per gallon back in June?

Summer's over dude, and has been for well over a month!

Although your boss' spokesman is chillin' from his job (such strange behavior with the national election less than six weeks away, but what should we expect when the boss himself has been phoning it in all this time!), maybe you should have spent more time working on real, non-election-related stuff for the last four months, because gas prices in the U.S. have spiked sharply upward. Again.

So, to help you better understand why you really don't want that to happen, we've updated our tool that allows you to roughly forecast what today's high gas prices will mean for tomorrow's soon-to-come unemployment rate in the U.S. Basically, we've incorporated all the available data through September 2012 and accounted for inflation through that month as well.

| |||

Just for fun, you should try this exercise using yesterday's average price of gasoline in California, $4.67.

"Good Morning, White House Staffer" is a special feature we run periodically whenever the average U.S. national retail price for gasoline rises above $3.50 per gallon!

Labels: forecasting, gas consumption, tool, unemployment

Now that the average price of gasoline in the United States is clocking in at all-time record levels for this time of year, especially in California, what effect will that factor have upon the official U.S. unemployment rate, which just clocked in at its lowest level since early 2009?

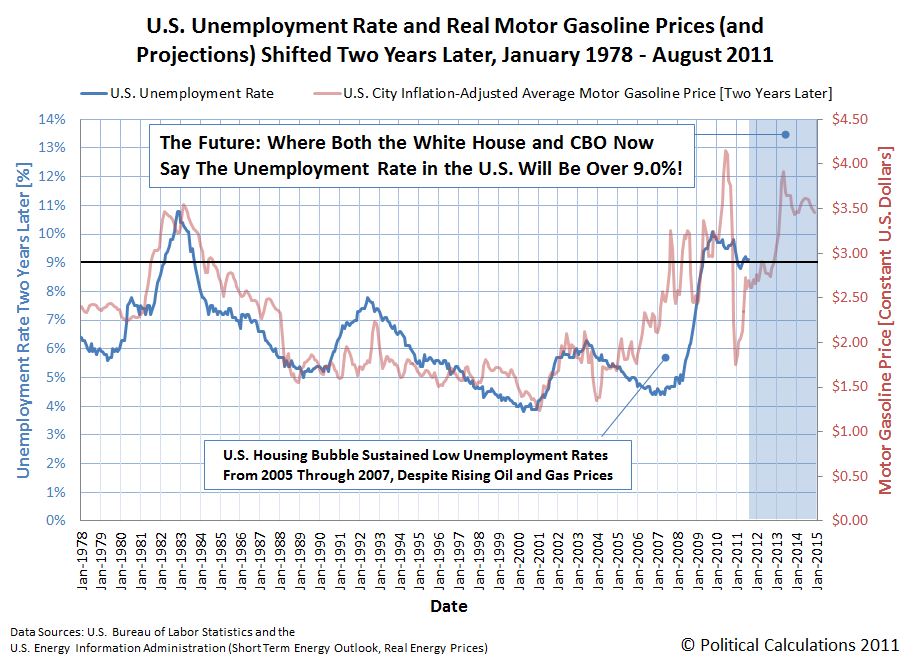

Unfortunately, that's the wrong question to be asking today, because it takes roughly two years for a major change in the price of oil and gasoline to play out and fully impact the U.S. unemployment rate. The right question to ask today is: "what was the price of gasoline doing two years ago that put the events in motion that are just now about to affect the U.S. economy?

The answer is revealed in our chart below, in which we've shifted the average price of motor gasoline in the United States forward in time by two years to visually correlate the price of gasoline with the recorded official U.S. unemployment rate for each month since January 1976 (or actually, since January 1978):

Here, we see that the U.S. unemployment rate has been tracking pretty closely with where the two-year time lagged price of gasoline in the U.S. would put it - including the "unexpectedly" low 7.8% unemployment rate that was just reported for September 2012.

The bad news is that if that correlation between the time-lagged price of gasoline and the U.S. unemployment rate continues, the U.S. is about to see a major spike upward in its unemployment rate, corresponding to the sustained surge in gasoline prices that began at the end of 2010.

It's only a coincidence that this surge in unemployment would appear set to take place just as the U.S. government approaches its self-created "fiscal cliff", where the ongoing failure of the Obama administration to negotiate government spending reductions in good faith with the U.S. Congress threatens to push the U.S. directly into recession in early 2013!

To start getting a feel for what the real forces are behind the relationship between oil and gasoline prices and the U.S. unemployment rate, let's turn to the San Francisco branch of the U.S. Federal Reserve's Dr. Econ for an explanation:

What effects do oil prices have on the "macro" economy?

I've just explained how oil prices affect households and businesses; it is not a far leap to understand how oil prices affect the macroeconomy. Oil price increases are generally thought to increase inflation and reduce economic growth. In terms of inflation, oil prices directly affect the prices of goods made with petroleum products. As mentioned above, oil prices indirectly affect costs such as transportation, manufacturing, and heating. The increase in these costs can in turn affect the prices of a variety of goods and services, as producers may pass production costs on to consumers. The extent to which oil price increases lead to consumption price increases depends on how important oil is for the production of a given type of good or service.

Oil price increases can also stifle the growth of the economy through their effect on the supply and demand for goods other than oil. Increases in oil prices can depress the supply of other goods because they increase the costs of producing them. In economics terminology, high oil prices can shift up the supply curve for the goods and services for which oil is an input.

High oil prices also can reduce demand for other goods because they reduce wealth, as well as induce uncertainty about the future (Sill 2007). One way to analyze the effects of higher oil prices is to think about the higher prices as a tax on consumers (Fernald and Trehan 2005). The simplest example occurs in the case of imported oil. The extra payment that U.S. consumers make to foreign oil producers can now no longer be spent on other kinds of consumption goods.

Despite these effects on supply and demand, the correlation between oil price increases and economic downturns in the U.S. is not perfect. Not every sizeable oil price increase has been followed by a recession. However, five of the last seven U.S. recessions were preceded by considerable increases in oil prices (Sill 2007).

Alan A. Carruth, Mark A. Hooker and Andrew J. Oswald connect the macro-economic dots then between yesterday's oil and gasoline prices and today's unemployment rates in their 1998 paper:

Intuitively, the mechanism at work is the following. An increase in, for example, the price of oil leads to an erosion of profit margins. Firms lose money, and begin to go out of business. To restore a zero-profit equilibrium, some variable in the economy has to alter. If labor and energy are the key inputs and interest rates are largely fixed internationally, it is labor's price that must decline.

But there is only one way in which this can happen. If wages and unemployment are connected inversely by a no-shirking condition, equilibrium unemployment must rise, because only that will induce workers to accept the lower levels of pay necessitated by the fact that the owners of oil are taking a larger share of the economy’s real income.

The same kind of process follows any rise in the real rate of interest. When capital owners' returns increase, the new zero-profit equilibrium requires workers’ returns to be lower. In a world where the level of unemployment acts as a "discipline device," higher real input prices lead to lower wages and greater unemployment rates.

This effect is what Obama administration officials are after in part when they state their political objective that the price of fuel must "necessarily skyrocket", as it gives the administration a target to scapegoat (capital owners) while simultaneously increasing their client base of unemployed individuals who will become dependent upon government-provided welfare for their income.

Or maybe they're just a bunch of screwups where all this can all be chalked up to "bad luck"....

Labels: forecasting, unemployment

According to Nomura Global Economics, there has been a rather dramatic divergence between the "real" and "official" unemployment rate in the United States since 2009. FT/Alphaville's Cardiff Garcia explains (HT: Tyler Cowen):

A chart via Nomura to keep in the back of your head as you eagerly anticipate this Friday's BLS employment situation report in the US:

In the grey line, Nomura economists have adjusted the unemployment rate for the number of discouraged workers who have left the labour force and therefore count as unemployed in this alternative measure.

(And yes, they do take into account demographic trends by age group that would influence those leaving, the largest of which is retiring baby boomers. So the right way to understand the alternative 10.3 per cent rate is that it includes those who have left the labour force but not those who, for structural reasons, would have left it anyways.)

Similar variations of this adjusted unemployment rate make headlines now and again. Our colleague Ed Luce, for instance, noted in December that "if the same number of people were seeking work today as in 2007, the jobless rate would be 11 per cent".

But what is striking about the broken line above isn't where it now ends — at 10.3 per cent — but rather the lack of any meaningful, sustained improvement for more than two years.

For those interested in how Nomura calculated its demographically-adjusted unemployment rate, Garcia followed up his initial reporting with more information from Nomura in an update (just scroll down!)

Our question arising from Nomura's chart though has to deal with the "official" U.S. unemployment rate: Why did it stop paralleling Nomura's adjusted unemployment rate in mid-to-late 2010?

We think we might have the answer: The expiration of President Obama's 99 weeks of unemployment benefits.

To understand why this may be the answer, you have to understand two key things about unemployment benefits: individuals may only collect them if they were laid off from a job and also if they claim they are seeking new employment.

So when individuals who receive unemployment benefits are asked if they are seeking work, as they might if they are surveyed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, they answer yes - even if they have really given up because their economic prospects are so bad.

Because they say they are looking for work, they are counted as being part of the U.S. labor force, which means they are added to the number of unemployed, which would act to inflate the U.S. unemployment rate above what it would otherwise see.

But when those benefits run out, they no longer need to maintain that fiction, so they don't. The "official" unemployment rate should rapidly fall upon their departure from the "official" civilian labor force after the expiration of their unemployment benefits.

We decided to put that to the test using the month-over-month change in the number of unemployed in the U.S. since November 2007, when total employment last peaked in the United States ahead of the December 2007 recession. The chart below shows the raw data for the overall civilian labor force (the data for which is collected throught the Census/BLS' Current Population Survey) and for the Manufacturing and Transportation & Warehousing sectors of the U.S. economy (the data for which is collected through the BLS' Current Economic Survey), which will allow us to track when layoffs in those industries affected the overall unemployment level:

What we'll next do is shift the curve for Total Unemployment some 103 weeks earlier in time. This value would correspond to the expiration of 99 weeks of unemployment benefits, plus an additional four weeks, which would account for the additional time lag for an individual whose unemployment benefits have expired and who would no longer need to claim they are seeking work to be reflected in the next monthly unemployment report.

What we see is that the magnitude of a decline in unemployment some 103 weeks later is nearly equivalent to the increase in unemployment 103 weeks earlier. We also see that the corresponding peaks and troughs in the time-shifted data occur most often between in a range between 99 weeks and 108 weeks, which might be attributable to delays in individuals filing for jobless benefits after being laid off or in reporting the change in their job-seeking status.

This result suggests that instead of the employment situation in the United States having become brighter, the decline of the "official" unemployment rate really reflects the economic discouragement of those who lost their jobs during the recession, as they face diminished economic prospects.

And that would be the primary reason for the divergence between Nomura's inclusive unemployment estimate and the U.S.' official unemployment rate.

Labels: jobs, unemployment

We're continuing our visual presentation of the data inside our "How Much Does It Cost to Employ You? (2011-12 Edition)" tool today with a look at the average tax rates paid by employers to support the unemployment insurance benefits mandated by the states in which they operate!

But, because we're always looking at new data visualization capabilities that we haven't previously explored, today, we're simultaneously showing all the data we have by state for each year from 2005 through 2011 in the chart below:

As we did with the workers' compensation tax rate data for 2010, we've posted an interactive version of the chart above and the source data at IBM's Many Eyes data visualization site.

Data Source

U.S. Department of Labor. Office of Workforce Security. Division of Fiscal and Actuarial Services. Significant Measures of State Unemployment Insurance Tax Systems. [2005, 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011]. Accessed 15 October 2011.

Labels: data visualization, taxes, unemployment

On Valentine's Day 2011, we explored the correlation that appears to exist between what motor gasoline prices are today and what the unemployment rate will be two years from now. At the time, we found that:

While the correlation is far from a perfect match, what we do see suggests that Americans can indeed use the real price of gas at the pump to reasonably anticipate how the unemployment rate will change two years down the road.

We then went on to create a tool where anybody can plug in the average price of gasoline today to forecast the U.S. unemployment rate two years later (we later simplified the tool, which is currently featured at the top of our website in our "Good Morning, White House Staffer" feature.)

At the time, we offered a vision of two possible scenarios based on the U.S. Energy Information Administration's projections of average U.S. motor gasoline prices that would play out through the end of 2012 (emphasis ours):

For example, using the default data for our tool, which takes the average retail price of motor gasoline in the United States from 21 February 2011 and pairs it with the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) from January 2011, our tool projects that the unemployment rate will be about 8.3%, which is lower that the 9.0% unemployment rate reported in January 2011, suggesting a mild improvement from now until then.

However, if average gasoline prices rise quickly to exceed $3.50 per gallon across the nation, as they already have in California, our tool would project that no significant improvement in the U.S. unemployment rate will take place over the next two years.

This year, we've watched the second scenario take hold. What's more, those higher gasoline prices have forced the White House to alter its view of how the U.S. economy will perform through the end of 2012 (emphasis ours, again):

President Obama's mid-session budget review confirms what most private and government projections have recently concluded -- that the economy is considerably weaker than earlier forecasts held, and won't fully recover from the Great Recession for years.

Most troubling, both for the country and for Obama politically, is that near-term unemployment is expected to remain significantly higher than expected, averaging 9 percent in fiscal year 2012.

Obama's budget office initially calculated its economic forecast based upon data available through June. Even that data presaged an 8.8 percent average unemployment rate in 2011 and an 8.3 percent average rate next year. But the mid-session review got delayed, and when the Office of Management and Budget revised it to incorporate the data through the end of August, the picture became much gloomier. Unemployment will average 9.1 percent this year, and 9.0 percent next year, OMB concluded, and won't dip below 7 percent until 2015 at the earliest.

Don't those numbers look familiar! Our site's "Good Morning, White House Staffer" feature would appear to be attracting its target audience!

But they would really rather you not think the much higher-than-they-expected unemployment rate they now expect through the end of 2012 has anything to do with the average retail price of gasoline in the United States:

The revised figures "reflect the substantial amount of economic turbulence over the past two months," OMB says, triggered by the European debt crisis, the earthquake in Japan, congressional brinkmanship over the debt ceiling among others. They also take into account the fact that GDP growth in the first half of fiscal year 2011 turned out to be significantly lower than originally thought.

Because that would mean having to admit that the higher-than-expected gasoline prices that we've seen this year are not so much an accident, but rather, a signature achievement of an administration that has consistently sought to increase gasoline prices in the U.S.:

Odd that the Obama administration wouldn't want to trumpet or draw attention to the successful achievement of another one of the President's major domestic policy objectives.

Instead, the President is becoming increasingly desperate as he tries to force the U.S. Congress to pass another massive stimulus package to try to "create or save" more jobs that even his party's leaders in the Senate are hesitant to take up.

Because maybe, just maybe, those White House staffers have finally worked up their own chart showing the correlation of average U.S. gasoline prices and the U.S. unemployment rate two years later, and realized that it looks like this:

Going by the elevated motor gasoline prices that have come to characterize Barack Obama's years as U.S. President, it appears that the U.S. unemployment rate will skyrocket up to 11% early in 2013 if the correlation between gasoline prices and the unemployment rate two years later continues to hold.

Regardless, whoever wins the Presidential election in November 2012 is going to have their work cut out for them in cleaning up what looks to be one big man-caused disaster.

Data Sources

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Short-Term Energy Outlook - Real Energy Prices. [Excel spreadsheet - monthly real U.S. City Average Motor Gasoline Prices]. Accessed 14 September 2011.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey, LNS14000000, Seasonally-Adjusted Unemployment Rate. Accessed 14 September 2011.

Previously on Political Calculations

- Surprising Impotence

- Who's Behind the Drop in Gas Prices?

- Changing the Outlook for Oil Prices

- Holy Gas Prices Batman! It's the New Batmobile!...

- Using Gas Prices to Forecast the Unemployment Trend

- Correlating the Price of Gas and the Unemployment Rate

- Why Are Americans Driving Less?

- How Much Does Your Commute Cost You?

- Should You Move Closer to Work to Save Commuting Costs?

- How to Save Money on Gas, Without Driving Less

- How Much Are Higher Gas Prices Really Hurting You?

- Should You Trade in Your Gas Guzzler?

- Is It Worth the Drive?

- Do Hybrids Really Save Money?

- How Much Do You Pay in Gas Taxes?

Labels: forecasting, gas consumption, unemployment

We now have enough data to be able to project the direction of the newest trend in U.S. layoff activity. The charts below reflect that new trend, for which we treated the seasonally-adjusted data for initial unemployment insurance claim filings of the week of 30 April 2011 as an outlier. The first chart represents the primary trends seen since 1 January 2006:

Our second chart narrows the bands for the range into which seasaonally-adjusted new jobless benefit claim filings are likely to fall while the new trend remains in force:

At present, it appears that the overall trend is negative, as it appears that jobless benefits will be likely to generally rise in the weeks ahead, although with such a limited number of data points to define the trend so far, there can be quite a bit of volatility in the direction of the trend until it becomes more established.

We've identified the data point for 30 April 2011 in both our charts as an outlier, as this coincides with a sharp seasonally-driven increase in new unemployment claims in New York state, as thousands of school workers in the state filed for unemployment insurance compensation during their schools' annual one week long spring break period, the timing for which wasn't fully accounted for in the Bureau of Labor Statistics' seasonal factor adjustments.

So they weren't really laid off, nor did they lose any job benefits, but apparently, in New York, it's okay to have a union job with the government's public schools and get unemployment benefits if you're scheduled to be off work for a week, because well, that unemployment check is just another job perk provided for by the taxpayers.

Meanwhile, we've also updated our table describing the major trends in U.S. layoff activity to include the newest trend:

| Timing and Events of Major Shifts in Layoffs of U.S. Employees | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Starting Date | Ending Date | Likely Event(s) Triggering New Trend (Occurs 2 to 3 Weeks Prior to New Trend Taking Effect) |

| A | 7 January 2006 | 22 April 2006 | This period of time marks a short term event in which layoff activity briefly dipped as the U.S. housing bubble reached its peak. Builders kept their employees busy as they raced to "beat the clock" to capitalize on high housing demand and prices. |

| B | 29 April 2006 | 17 November 2007 | The calm before the storm. U.S. layoff activity is remarkably stable as solid economic growth is recorded during this period, even though the housing and credit bubbles have begun their deflation phase. |

| C | 24 November 2007 | 26 July 2008 | Federal Reserve acts to slash interest rates for the first time in 4 1/2 years as it begins to respond to the growing housing and credit crisis, which coincides with a spike in the TED spread. Negative change in future outlook for economy leads U.S. businesses to begin increasing the rate of layoffs on a small scale, as the beginning of a recession looms in the month ahead. |

| D | 2 August 2008 | 21 March 2009 | Oil prices spike toward inflation-adjusted all-time highs (over $140 per barrel in 2008 U.S. dollars.) Negative change in future outlook for economy leads businesses to sharply accelerate the rate of employee layoffs. |

| E | 28 March 2009 | 7 November 2009 | Stock market bottoms as future outlook for U.S. economy improves, as rate at which the U.S. economic situation is worsening stops increasing and begins to decelerate instead. U.S. businesses react to the positive change in their outlook by significantly slowing the pace of their layoffs, as the Chinese government announced how it would spend its massive economic stimulus effort, which stood to directly benefit U.S.-based exporters of capital goods and raw materials. By contrast, the U.S. stimulus effort that passed into law over a week earlier had no impact upon U.S. business employee retention decisions, as the measure was perceived to be excessively wasteful in generating new and sustainable economic activity. |

| F | 14 November 2009 | 11 September 2010 | Introduction of HR 3962 (Affordable Health Care for America Act) derails improving picture for employees of U.S. businesses, as the measure (and corresponding legislation introduced in the U.S. Senate) is likely to increase the costs to businesses of retaining employees in the future. Employers react to the negative change in their business outlook by slowing the rate of improvement in layoff activity. |

| G | 18 September 2010 | 2 April 2011 | Possible multiple causes. Political polling indicates Republican party could reasonably win both the U.S. House and Senate, preventing the Democratic party from being able to continue cramming unpopular and economically destructive legislation into law, bringing relief to distressed U.S. businesses. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke announces Federal Reserve will act if economy worsens, potentially restoring some employer confidence. The White House announces there will be no big new stimulus plan, eliminating the possibility that more wasteful economic activity directed by the federal government would continue to crowd out the economic activity of U.S. businesses. |

| H | 9 April 2011 | Present | Rising oil and gasoline prices exceed the critical $3.50-$3.60 per gallon range (in 2011 U.S. dollars), forcing numerous small businesses to act to reduce staff to offset rising costs in order to prevent losses. |

If the current projected trajectory for the new trend holds, we would anticipate a 68.2% chance of the number of seasonally-adjusted new jobless claim filings for the week of 4 June 2011 to be between 417,800 and 439,400. There is a 99.7% probability that number will fall between 396,200 and 461,000.

We're pretty sure this isn't shaping up to be the kind of "recovery summer" the Obama administration was hoping would change their fortunes for the better last summer, but didn't. We suppose there's always next year.

Labels: jobs, unemployment

We've been in the midst of a data conversion project behind the scenes here at Political Calculations, in which we've been upgrading our previously generated analyses that were maintained in Microsoft Excel's 2003 format to the newer 2010 format. As part of that project, we have also been automating various aspects of our analytical techniques, so we don't have to work as hard to divine what we can from the data we read.

Today, we're showing off the first stage of what we've done with weekly U.S. seasonally-adjusted initial unemployment insurance claim filings, where we've previously applied statistical control chart-type analysis to identify major trends and turning points in U.S. layoff activity.

Here, we've automated the "red flags" given by Western Electric's four major rules for detecting when an established trend might be breaking down, which in turn, allows us to more precisely track changes in trends over time.

As a result, we've refined our previous presentation of the seasonally-adjusted major trends in U.S. layoff activity, which we've presented in the chart below, where we've arbitrarily selected the first weekly new unemployment claims report of 2006 as our starting point.

The table below lists the corresponding dates that apply to each identified trend, as well as the likely trigger that caused the shift initiating the trend. Here, we identify news events that could cause employers to revise their existing outlook for their employee retention decisions that occurred in the 2-3 weeks prior to the shift in trend taking hold.

This 2-3 week period of time is consistent with the practice of employers reacting to a change in their business outlook with their next payroll cycle, without altering their current payroll cycle. In the United States, since most employees are paid on a weekly or biweekly basis, that translates to our two-to-three week long window of time for a such a reaction to an outlook-changing event to be reflected in the government's official data.

| Timing and Events of Major Shifts in Layoffs of U.S. Employees | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | Starting Date | Ending Date | Likely Event(s) Triggering New Trend (Occurs 2 to 3 Weeks Prior to New Trend Taking Effect) |

| A | 7 January 2006 | 22 April 2006 | This period of time marks a short term event in which layoff activity briefly dipped as the U.S. housing bubble reached its peak. Builders kept their employees busy as they raced to "beat the clock" to capitalize on high housing demand and prices. |

| B | 29 April 2006 | 17 November 2007 | The calm before the storm. U.S. layoff activity is remarkably stable as solid economic growth is recorded during this period, even though the housing and credit bubbles have begun their deflation phase. |

| C | 24 November 2007 | 26 July 2008 | Federal Reserve acts to slash interest rates for the first time in 4 1/2 years as it begins to respond to the growing housing and credit crisis, which coincides with a spike in the TED spread. Negative change in future outlook for economy leads U.S. businesses to begin increasing the rate of layoffs on a small scale, as the beginning of a recession looms in the month ahead. |

| D | 2 August 2008 | 21 March 2009 | Oil prices spike toward inflation-adjusted all-time highs (over $140 per barrel in 2008 U.S. dollars.) Negative change in future outlook for economy leads businesses to sharply accelerate the rate of employee layoffs. |

| E | 28 March 2009 | 7 November 2009 | Stock market bottoms as future outlook for U.S. economy improves, as rate at which the U.S. economic situation is worsening stops increasing and begins to decelerate instead. U.S. businesses react to the positive change in their outlook by significantly slowing the pace of their layoffs, as the Chinese government announced how it would spend its massive economic stimulus effort, which stood to directly benefit U.S.-based exporters of capital goods and raw materials. By contrast, the U.S. stimulus effort that passed into law over a week earlier had no impact upon U.S. business employee retention decisions, as the measure was perceived to be excessively wasteful in generating new and sustainable economic activity. |

| F | 14 November 2009 | 11 September 2010 | Introduction of HR 3962 (Affordable Health Care for America Act) derails improving picture for employees of U.S. businesses, as the measure (and corresponding legislation introduced in the U.S. Senate) is likely to increase the costs to businesses of retaining employees in the future. Employers react to the negative change in their business outlook by slowing the rate of improvement in layoff activity. |

| G | 18 September 2010 | Present | Possible multiple causes. Political polling indicates Republican party could reasonably win both the U.S. House and Senate, preventing the Democratic party from being able to continue cramming unpopular and economically destructive legislation into law, bringing relief to distressed U.S. businesses. Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke announces Federal Reserve will act if economy worsens, potentially restoring some employer confidence. The White House announces there will be no big new stimulus plan, eliminating the possibility that more wasteful economic activity directed by the federal government would continue to crowd out the economic activity of U.S. businesses. |

We've also projected the current trend in U.S. layoff activity in our chart through the end of June 2011. The region between the light purple lines indicating the plus-or-minus one standard deviation from the mean trend line is the most likely region in which the data will fall going forward through that time, absent a break in the current trend.

If the current trend does hold, we can expect new seasonally-adjusted unemployment insurance claim filings to fall in the range between 360,540 and 409,963 for the week of 23 April 2011, the limits of which would then steadily fall by about 2,270 filings each week until reaching a range between 337,835 and 387,257 by 2 July 2011.

Those ranges seem to be awfully wide, but we do have another trick up our sleeve for narrowing down the likely range into which new unemployment insurance claims will fall, which we'll share soon.

Image Credit: MiC Quality

Labels: forecasting, quality, unemployment

Previously, we found that the average price of a gallon of gasoline in the U.S. can be used to forecast what the U.S. unemployment rate will be about two years ahead in time.

Since then, gasoline prices have been rising pretty significantly across the U.S. and are predicted to rise even further, so today, we're presenting a tool based upon our analysis that you can use to anticipate what the jobs situation will be like two years from now.

To find out, enter the latest average price of a gallon of gas in the U.S. into the tool as well as the most recently available value for the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, which lets us take inflation into account, and we'll project what the U.S. unemployment rate will likely be two years from now.

Now for a quick word of caution. The correlation between gas prices and the unemployment rate is positive, but is only of low-to-medium strength, which you can see in the spread of the data points about the trend line in our chart showing the correlation.

What that means is that while higher gasoline prices do generally translate into a higher unemployment rate two years into the future and lower gasoline prices translate into lower unemployment rates, the actual unemployment rate two years from now can be significantly different from what the tool forecasts.

As such, our tool is best used to anticipate the general trend in the unemployment rate rather than the specific unemployment rate.

For example, using the default data for our tool, which takes the average retail price of motor gasoline in the United States from 21 February 2011 and pairs it with the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) from January 2011, our tool projects that the unemployment rate will be about 8.3%, which is lower that the 9.0% unemployment rate reported in January 2011, suggesting a mild improvement from now until then.

However, if average gasoline prices rise quickly to exceed $3.50 per gallon across the nation, as they already have in California, our tool would project that no significant improvement in the U.S. unemployment rate will take place over the next two years.

Previously on Political Calculations

- Correlating the Price of Gas and the Unemployment Rate

- Why Are Americans Driving Less?

- How Much Does Your Commute Cost You?

- Should You Move Closer to Work to Save Commuting Costs?

- How to Save Money on Gas, Without Driving Less

- How Much Are Higher Gas Prices Really Hurting You?

- Should You Trade in Your Gas Guzzler?

- Is It Worth the Drive?

- Do Hybrids Really Save Money?

- How Much Do You Pay in Gas Taxes?

Labels: gas consumption, tool, unemployment

We were intrigued by a chart Robert Zubrin posted illustrating that spikes in the inflation-adjusted price of oil have often preceded changes in the U.S. unemployment rate. So much so that we wondered if a similar pattern might emerge if we substituted the average price of gasoline at the pump instead.

There are two big reasons why we are so curious to see if that kind of pattern exists. The first reason has to do with the much greater visibility of motor gasoline prices in the United States as compared to the price of a barrel of oil. It's really the only commodity whose price you can see prominently advertised in every community in the nation and one that nearly every driving American can tell you off the top of their head.

The second reason has to do with the strong, negative correlation of gasoline prices and presidential approval ratings, where rising gas prices coincide with falling approval levels and falling prices correlate with improving approval ratings in public polling.

If the real price of gasoline at the pump really is correlated with changes in the unemployment rate, that relationship would go a long way to both justifying Americans' use of the price of gas as a measure of a President's performance in office!

Let's get to it then! Our first chart takes monthly unemployment rate data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics and matches it up with the average, inflation-adjusted U.S. city price of motor gasoline from the U.S. Energy Information Agency from January 1976 onward. We selected this starting date because it coincides with the earliest data available from the EIA regarding the price of unleaded motor gasoline, which has been continuously available in the U.S. since.

What we see is that spikes in the real price of gasoline at the pump tend to lead spikes in the U.S. unemployment rate by roughly two years. We next shifted the unemployment rate data leftward (earlier) by 24 months to better show that apparent correlation.

While the correlation is far from a perfect match, what we do see suggests that Americans can indeed use the real price of gas at the pump to reasonably anticipate how the unemployment rate will change two years down the road. We next determined the overall strength of this correlation.

With an R2 coefficient of determination of 0.545, which suggests that the price of oil can "explain" some 54.5% of the variation in the U.S. unemployment rate two years later, we find that there is a positive, but only medium-strength correlation between the two.

It's far from perfect, but that correlation means that Americans can indeed use their personal perceptions of the cost of gas at the pump as a measure of how well the President is doing their job overall, because how they'll be doing economically two years from now will very likely be impacted!

Data Sources

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Seasonally-adjusted Unemployment Rate, 16 Years and Over. Accessed 9 February 2011.

U.S. Energy Information Administration. Short-Term Energy Outlook - Real Energy Prices (Excel Spreadsheet). Accessed 9 February 2011.

Image Credit: Scoreboards.net

Labels: gas consumption, unemployment

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.