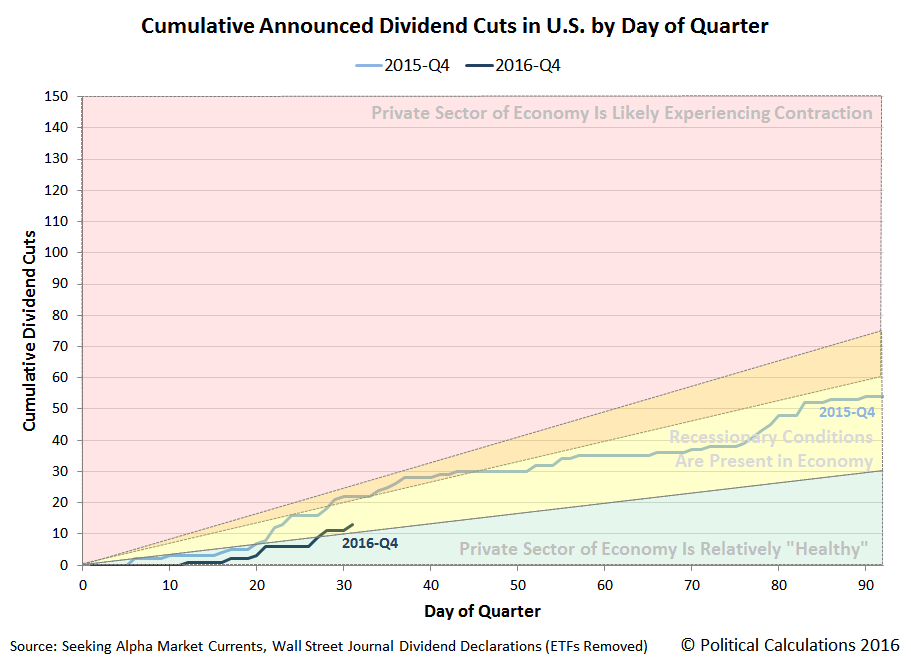

We're awaiting S&P's month end official tally of the number of dividend cuts in October 2016 later today, but until then, we do have a sense of the relative health of the private sector of the U.S. economy from our real time sources that report the dividend declarations of U.S. firms. Our first chart reveals what they indicate for how 2016-Q4 is playing out so far, as compared to the previous three quarters (2016-Q1, 2016-Q2 and 2016-Q3):

We first confirm that recessionary conditions continue to be present within the U.S. economy, but at a reduced level with respect to the first two quarters of 2016. They are however consistent what what we observed through the same point of time in 2016-Q3, which would so far appear to have seen the strongest growth in the year to date.

We also confirm year over year improvement in economic performance through our chart comparing the current quarter to date against the number of dividend cuts that was recorded through this point of time in 2015-Q4.

The reason for the improvement is fairly straight forward - there is considerably less distress in the oil production sector of the U.S. economy thanks to relatively higher oil prices, which bottomed in February 2016, and have since recovered to today's level near $50 per barrel.

Consequently, there are a lot fewer oil producing firms announcing that they need to cut their dividends these days. Then again, there are also fewer oil producing firms these days.

Data Sources

Seeking Alpha Market Currents. Filtered for Dividends. [Online Database]. Accessed 31 October 2016.

Wall Street Journal. Dividend Declarations. [Online Database]. Accessed 31 October 2016.

Labels: dividends

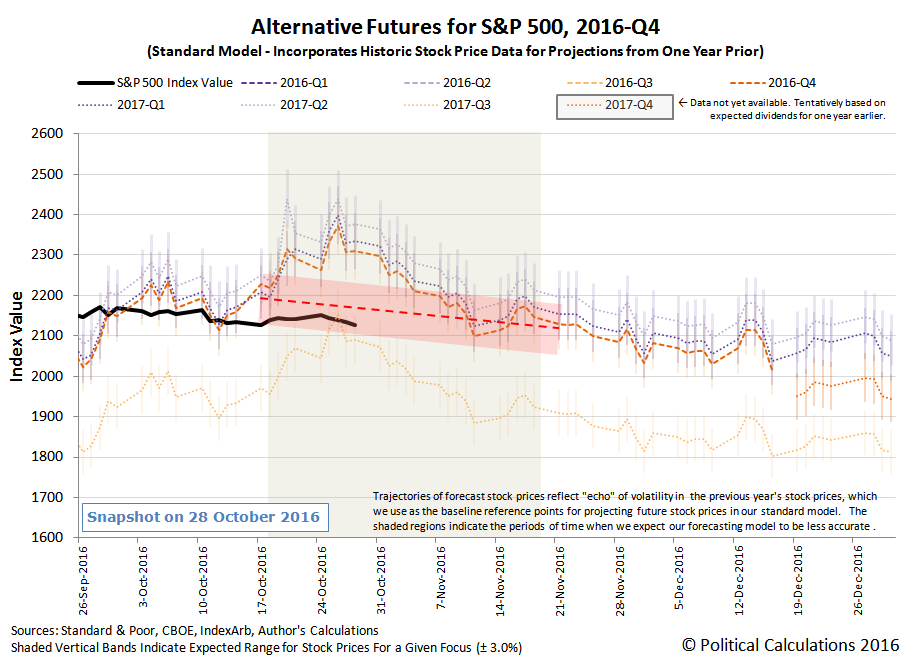

In the fourth week of October 2016, the S&P 500 ended the week lower than it began, as stock prices also fell from the level at which they closed in Week 3.

But that's not what people will remember about the market close at the end of the week, since the S&P 500 only dropped on Friday, 28 October 2016 in response to what we would describe as a political noise event.

And since politics rarely ever drive stock prices, the market experienced little more than a hiccup in terms of its typical daily volatility.

In the absence of other such noise events, or changes in fundamental factors that could more seriously influence stock prices, we can reasonably expect stock prices in the near future to converge with the red-dashed line trajectory we sketched on the chart above two weeks ago. After that happens, stock prices will more likely than not resume their generally downward trajectory, although the only thing we would really expect is that they fall somewhere within the red-shaded range we've indicated on the chart above, consistent with our assumption that investors will continue to focus on the current quarter of 2016-Q4 and will make their investing decisions in accordance with its corresponding expectations.

Although the week was, by far, the busiest to date at this point of 2016-Q4's earnings season, there weren't all that many headlines with market moving potential during the week. The handful that we identified are listed below.

- Monday, 24 October 2016

- Fed's Bullard says one rate increase is all that's needed for now. Looking beyond that, another Fed official who supports a very gradual pace for future interest rate hikes says that the Fed needs to get to inflation goal sooner: Evans

- Wall St. touches two-week high on deals, strong earnings

- Wall Street slips as energy, consumer stocks drag

- Tuesday, 25 October 2016

- Wednesday, 26 October 2016

- Thursday, 27 October 2016

- Friday, 28 October 2016

- First headline: Wall St. rises amid robust earnings, GDP data - Final headline: Wall St. falls as FBI to review more Clinton emails

- How the bond market began the day: U.S. Treasury yields rise after stronger-than-expected GDP data - What happened later: U.S. Treasury yields fall on news FBI to reopen Clinton email probe. This is a prime example of how a political event can contribute to the typical daily noise of the markets, but without significantly driving them, as the value of the S&P 500 closed the day down by 6.63 points (0.3%), bringing it to almost the same level it was just nine trading days ago!

For a more complete picture of the week that was, Barry Ritholtz identifies what he saw as the positives and negatives of the week's market and economic news.

We have an odd, nearly annual tradition here at Political Calculations, where when we get to this time of year, we celebrate the kind of inspired design that goes into what might be described as really spooky furniture.

And since 2016 has been a year in which advances in the technology behind self-driving automobiles has captured widespread public attention, what could be an either better or spookier way to continue that tradition than to point out where these two trends have unexpectedly intersected?

Hang on to your seats, because you're about to witness the unattended manipulation of common, ordinary chairs of a kind that's typically not seen outside horror movies involving poltergeists, demonic possession or a very dystopian future.

HT: Core77, who notes that this isn't just a one time stunt, but rather, is something that marks the invention of a whole brand new class of technology. Just imagine what it might mean for your office....

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: technology

Yesterday, the U.S. Census Bureau released its latest data on the average and median sale prices of new homes in the United States, with the newest data being reported for September 2016.

Much less noticed, the Census Bureau also revised each of the new home sale prices it previously reported over the preceding three months, affecting the data reported for June 2016, July 2016 and August 2016. Depending upon your media source, you may only have been aware of as many as two of those revisions of previous data.

Those revisions are a regular practice of the U.S. Census Bureau, which provides an initial estimate for the sale prices of new homes for each month it reports before revising it three more times over the next three months, where the fourth estimate represents the final estimate it publishes.

We became curious to see how much the estimates changed from first through fourth estimate, so we began tracking them beginning with the initial estimate published for December 2014. The results of that project are visually presented in the following chart, which shows a pretty remarkable pattern for the Census Bureau's reported median new home sale prices from their first through fourth and final estimate that receives almost no attention in the media.

Four the 19 months for which we have four estimates of new home sale prices, spanning December 2014 through June 2016, we see that the second revision is the only one where the prices are more likely to be revised downward than upward, with 52% (10 of 19) being changed that way. After the second revision however, the upward revisions dominate, with 79% (15 of 19) of third revisions being adjusted above the second revision, and 84% (16 of 19) of fourth revisions being adjusted to be larger than the third revision.

Cumulatively, those adjustments combine to produce the result where 89% (17 of 19) of the fourth and final estimate is reported to be higher than the initial estimate. Over the period of time for our sample, the final estimate is on average some 3.3% higher than the initial estimate, although that ranges from a low of -1.5% to a high of 8.1%.

As the Census Bureau reports and revises its data, it reflects the increasing amount of information it has on the number of new home sales and their sale prices. Often, its initial estimates omit data for homes that have sold for higher prices, which tend to take longer to be reported, which would explain why the later estimates tend to be revised upward over time.

But perhaps the real question is why is that second estimate adjusted downward so much more often in comparison to later estimates?

Labels: data visualization, real estate

Periodically in the course of the various projects we're developing, we come across data that's interesting in and of itself. Today, that data is about the business of business jets, in which we're looking at the number of new business jets manufactured in the United States in the years from 2002 through the present.

When new, business jets can carry price tags of anywhere between $3 million and $65 million, where at the typical sales price of $20 million for a midsize business jet, a change of just 50 sales in a single year can represent a billion dollar swing in the economy.

That makes the 55% decline in the industry that occurred in 2009 and 2010 an especially dramatic event. Lagging behind the official starting and ending dates of the Great Recession, the U.S. business jet industry effectively shrank its annual production by somewhere in the ballpark of $10 billion.

Something similar happened on a considerably smaller scale between 2012 and 2013, where the total number of business jets made in the USA fell by 10%. That microrecession directly led to Hawker Beechcraft's bankruptcy, where the company discontinued making business jets altogether as part of its subsequent reorganization. The company today is owned by Textron (NYSE: TXT), the parent company of Cessna, which manufactures a line of small to mid-size business jets.

Cessna's production was also hammered during the Great Recession, like all manufacturers, and uniquely between 2012 and 2013.

Sales of business jets were expected to improve in 2013 after being hit last year by fears of a "fiscal cliff". However, mandatory U.S. government spending cuts have made small business owners - Cessna's main customers - cautious about big purchases.

"There's rumored money sitting on the sidelines, waiting for clarity in the economy," said Jens Hennig, vice-president of operations at General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA).

Global shipments of business jets fell 4 percent to 283 aircraft in the first half of 2013, according to GAMA, which represents more than 50 fixed-wing aviation aircraft makers, including Cessna.

Part of that negative business climate was directly generated by President Obama, who specifically targeted the buyers of business jets for criticism during his first term and also during the 2012 presidential debates. President Obama also proposed the budget sequester that produced the cuts in federal government spending cited by small business leaders as a leading reason for why they put off acquiring business jets during this time.

The only U.S. business jet manufacture to gain market share during this time was Gulfstream, a wholly owned subsidiary of General Dynamics (NYSE: GD), thanks largely to the introduction of two new models in late 2012, the G280 and the G650, the latter of which opened up a new niche in the business jet market: large-cabin executive jets. These new planes would fall in between the mid-size cabin aircraft manufactured by Cessna and Boeing's converted commercial transport aircraft, and proved especially popular with global customers, particularly in the Middle East.

Flashing forward to 2016 however, reports indicate that the market for Gulfstream's large-cabin business jets has begun slipping compared to previous years, while Canada's Bombardier, which manufactures Learjets and its Challenger 300/350 model in the United States, has seen sales drop by nearly one third. At the same time, Cessna's sales are projected to rise during the year, thanks in part to new models it has begun producing.

And then, there's Boeing, whose business jet business represents a small fraction of its overall sales, which are pretty stable from year to year at a very low number.

References

General Aviation Manufacturers Association (GAMA). General Aviation 2000 Statistical Databook. Table 1.4a. Worldwide Business Jet Shipments by Manufacturer (2002-2015). [PDF Document]. 29 March 2016.

Labels: business, data visualization

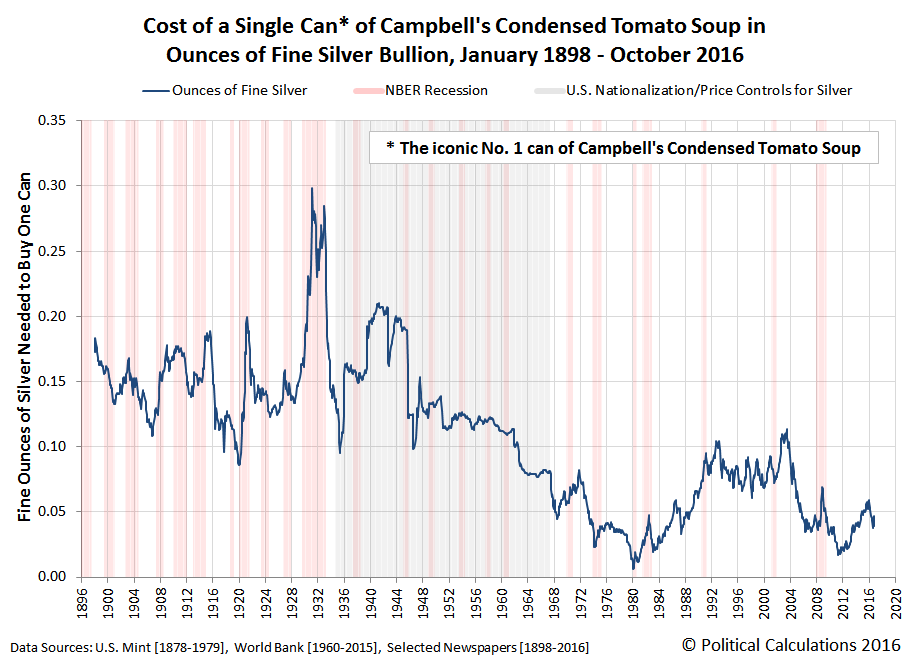

Once upon a time, and for a very long time, Americans could buy a single can of Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup for the price of just one dime.

And for much of the time when Americans could buy a can of condensed tomato soup for a dime, U.S. dimes were made of silver. Or more specifically, they were made of "junk silver", which means that they were made of 90% silver and 10% copper by weight.

Since nearly all of their value was derived from their silver content, for all practical purposes, Americans paid for their soup with silver. We wondered how many ounces of silver it would take to buy a single Number 1 can of Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup in any month throughout its entire history, even after U.S dimes stopped being made from silver in 1965. Seeing as we have all those monthly prices for silver going back to 1880, we were able to generate the following chart showing how many fine ounces of silver bullion it would take to buy a can of Campbell's Tomato Soup in each month since January 1898, which is as far back as we have that price data.

In terms of its equivalent value in silver, Campbell's Tomato Soup has become more affordable, where since U.S. price controls over silver were ended after 1967, the relative price of soup has dropped from a typical range of 0.10-0.20 ounces per can to a range of 0.02 to 0.12 ounces per can.

By contrast, the average price of a can of Campbell's Condensed Tomato Soup in U.S. dollars has risen from $0.10 in 1967 to $0.80 as of October 2016, a factor of 8X. Over the same time, the price of one fine ounce of silver has risen by 15X in terms of U.S. dollars. Meanwhile, since 1967, the price of gold is up over 35X.

Since we're coming up on Halloween, which do you suppose would be the more useful form of currency after the zombie apocalypse?

Labels: data visualization, food, inflation

In the third full week of October 2016, the S&P 500 ended higher than it closed in Week 2 of October 2016.

And yet, the week had something of a downcast to it, as can be seen in our alternative futures chart.

As expected, our futures-based model's projections of the alternate paths the S&P 500 would be likely to take based on how far forward in time investors are looking was off target, which is a result of our standard model's use of historic stock prices as the base reference points from which it projects future stock prices. In this case, the indicated trajectories for the period from 18 October 2016 to 21 November 2016 represents an echo of the noisy volatility that the S&P 500 experienced a year ago.

However, our "connect-the-dots" method of compensating for the echo effect to improve the accuracy of our forecast trajectory appears to be working - at least through the first several days in which we would need it to!

But it will need to continue working over the next four weeks for it to be really worthwhile. Until then, we suspect that how we visualized the connected dots trajectory in the chart above is what really gives the week its downcast feel.

Speaking of which, here are the headlines that caught our attention during Week 3 of October 2016.

- Monday, 17 October 2016

- Over the weekend: Fed's Fischer: downshift in potential means 'not that simple' to raise rates - on Monday: Fed 'very close' to employment, inflation goals: Fischer

- Boston Fed's Rosengren maps case for a dove's rate hike

- Oil ends lower on U.S. trade spike; shale decline limits losses

- Wall Street slips as energy, consumer stocks drag

- Tuesday, 18 October 2016

- Wednesday, 19 October 2016

- Thursday, 20 October 2016

- Friday, 21 October 2016

- S&P, Dow fall with health stocks; Microsoft lifts Nasdaq

- A Fed's Williams Trifecta! Fed's Williams says 'this year would be good' for rate increase, Fed's Williams wants rate hike this year as wages rise, and also Fed is trying to make policy as predictable as possible: Williams

- Wall Street ends little changed; Microsoft hits record

Barry Ritholtz succinctly summarizes the positives and negatives of the week's market and economic news.

When junk science goes unchallenged, it can have real world consequences.

In today's example of junk science, we have a case where the real world consequences involve taxes being selectively imposed on a single class of products that is commonly purchased by millions of consumers, soda pop, because of the perceived harm to people's health that is believed to result from the excessive consumption of a single one of its ingredients, sugar.

What makes this an example of junk science is the combination of ideological and cultural goals of the proponents of the city's soda tax and the inconsistencies associated with their proposed solution to deal with it, in which they are ignoring thousands of other foods and beverage products that also contain similar levels of sugar in its various forms (sucrose, fructose, et cetera), which will not also be subjected to the tax aimed at solving a perceived public health issue. The table below lists the specific items from our checklist for how to detect junk science that apply to today's example.

| How to Distinguish "Good" Science from "Junk" or "Pseudo" Science | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspect | Science | Pseudoscience | Comments |

| Goals | The primary goal of science is to achieve a more complete and more unified understanding of the physical world. | Pseudosciences are more likely to be driven by ideological, cultural or commercial (money-making) goals. | Some examples of pseudosciences include: astrology, UFOlogy, Creation Science and aspects of legitimate fields, such as climate science, nutrition, etc. |

| Inconsistencies | Observations or data that are not consistent with current scientific understanding generate intense interest for additional study among scientists. Original observations and data are made accessible to all interested parties to support this effort. | Observations of data that are not consistent with established beliefs tend to be ignored or actively suppressed. Original observations and data are often difficult to obtain from pseudoscience practitioners, and is often just anecdotal. | Providing access to all available data allows others to independently reproduce and confirm findings. Failing to make all collected data and analysis available for independent review undermines the validity of any claimed finding. Here's a recent example of the misuse of statistics where contradictory data that would have avoided a pseudoscientific conclusion was improperly screened out, which was found after all the data was made available for independent review. |

As part of the discussion related to today's example of junk science, you'll also see the phrase "Pigovian tax". These are named after British economist A.C. Pigou, who proposed that imposing taxes on things or activities that produce undesirable consequences would lead to less of the undesirable consequences, assuming that lawmakers set that kind of tax to the correct level to compensate for the cost of the negative consequences and impose it everywhere it needs to be imposed to achieve the intended result.

Otherwise, what you will get will closely resemble today's example of junk science, where one city's lawmakers are making a total hash out of nutrition science, public health, and tax policies.

Busybodies in the American public, never content to leave other people alone, always seem to need a common enemy to rally against. For years, it was McDonald's. Then it was Monsanto and Big Pharma. Now, it's Big Soda.

At first glance, a war on soda might appear to make sense. There is no nutritional benefit to soda. Given the large and growing segment of the U.S. populace that is obese or contracting type 2 diabetes, perhaps a Pigovian tax on soda (with the aim of reducing soda consumption) makes sense. After all, the science on sugar is pretty clear: Too much of it in your diet can lead to health problems.

But a closer look at food science reveals that a tax on sugary drinks (such as soda, sports drinks, and tea), a policy being pondered by voters in the San Francisco Bay area, is deeply misguided. We get sugar in our diets from many different sources, some of which we would consider "healthy" foods.

A 12-oz can of Coke has 39 grams of sugar. That's quite a bit. How does that compare to other foods? You might be surprised.

Starbucks vanilla latte (16 oz) = 35 grams

Starbucks cupcake = 34 grams

Yogurt, sweetened or with fruit (8 oz) = 47 grams

Homemade granola (1 cup) = 24.5 grams

Grape juice (8 oz) = 36 grams

Mango (1 fruit without refuse) = 45.9 grams

Raisins (A pathetic 1/4 cup) = 21 grams

If these food activists were consistent, they would also advocate for a tax on fruit juice, granola, and coffee. But considering that these very same activists are probably vegan, organic food-eating granola-munchers, they're not going to do that. The truth is, moderation is key to a healthy diet and preventing diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes*. But that simple message is boring, and it doesn't excite nanny state activists.

Furthermore, if proponents of a soda tax were actually serious about reducing diseases related to poor nutrition, they would endorse a public health campaign aimed at raising awareness of the sugar content found in all foods. Or, they might endorse a Pigovian tax on all high-sugar foods. But, they won't do that, either, because it would be widely despised, as people strongly dislike paying large grocery bills. So instead, they demonize Big Soda, which is politically popular.

And that is the very definition of a feel-good policy based on junk science.

*It should also be pointed out that food choices are only one factor among many that determine whether a person becomes obese or develops type 2 diabetes. Genetics, weight, and physical inactivity also play roles.

Unfortunately, the field of nutrition science has often been the victim of pseudoscientific research and practices.

In today's example, the nutrition pseudoscience that argues that only sugary soda beverages should be taxed to deal with the negative consequences of excessive sugar consumption has intersected with the self-interest of politicians who strongly desire to boost both their tax revenues and their power over the communities they govern without much real concern about seriously addressing the public health issues that they are using to justify their policies.

The way you can tell if that's the case is what they do with the money from the taxes they collect. If any part of that money is diverted to other unrelated purposes, such as to pay public employee pensions for example, then it is a safe bet that they never believed the public health problems they said they would solve by imposing such taxes were anywhere near as great as they claimed.

And unfortunately, like the junk science on which such poor public policy is based, you often won't find out until long after the damage has been done.

References

Berezow, Alex. San Francisco Soda Tax: A Feel-Good Policy Based On Junk Science. [Online Article]. American Council on Science and Health. 29 September 2016. Republished with permission.

Labels: junk science

Since the Affordable Care Act's health insurance "marketplaces" first went online back in October 2013, we've been proud to offer a unique tool that subsidy-eligible American consumers can use to make the right choice for themselves in shopping for health insurance with respect to their personal financial situation and their health.

That tool will tell you whether it makes more financial sense to buy health insurance through the Obamacare exchanges or to opt out and pay higher income taxes instead, depending upon whichever of these options is less costly for you.

According to recently released IRS statistics, that is a choice that million of Americans have been making since 2014, where after performing similar calculations on their own and finding out how actually "affordable" the Affordable Care Act's health insurance policies are with respect to whatever additional tax they might otherwise have to pay after considering the state of their health. The IRS confirms that in 2014, the first for which Americans had to either demonstrate that they had health insurance coverage or else be subject to a "shared responsibility" tax penalty, some 8,061,604 Americans chose the penalty over paying any health insurance premiums.

The Obamacare tax collectively cost them $1.694 billion, which works out to an average tax paid of $210.14 per income tax return for those who were subject to the tax. By contrast, the average monthly unsubsidized premium for a health insurance plan through the Affordable Care Act exchanges for 2014 was $328, which corresponds to a total cost of $3,926 per year for health insurance coverage.

It would have taken annual tax subsidies of at least $3,716 to have made signing up for health insurance through the Obamacare exchanges a slam dunk choice from a personal finance perspective that year, and though the penalty income tax has since increased to its now maximum rate, which changes where that threshold now lies, similar personal finance math still applies today!

Our tool below will help you decide which option may be more affordable for you in 2017. Beginning on 1 November 2016, you can obtain the relevant health insurance policy cost information you need from either the Healthcare.gov web site, or more reliably, from the independent and far more transparent Health Sherpa site. The default data in the tool below applies for 2017 premium data that has already been published for Pueblo, Colorado.

Also, if you're accessing this tool on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a working version of our tool.

About This Tool

In building this tool, we've made a handful of assumptions. Here they are, along with links to our references for data:

- The federal government's poverty income thresholds for 2013 will initially apply in 2014.

- The Kaiser Family Foundation's description of how ObamaCare's subsides will be calculated is accurate.

- The map of states we used to identify which are expanding their eligibility for their Medicaid programs up to 138% of the federal poverty income threshold and which are not is largely accurate. For states that had not made their determination as 1 September 2013, we've assumed that they are not expanding their Medicaid program's eligibility. We will update this periodically as new information becomes available.

- CNNMoney's description of how the penalty tax will work is accurate. We also thank Sean Parnell of The Self-Pay Patient blog, who identifies an exemption from the tax that we originally missed - it turns out that people who live in regions where the lowest-cost Bronze plan is more than 8% of their household income even after the subsidy will be fully exempt from the tax! (Of course, you realize that means that skipping out on not paying health insurance too until they might actually need it just became an even more attractive option for those who will be fully exempt from the tax!)

- The default values associated with selecting the "United States" are those that will apply for a majority of the nation's population.

- People will mostly act rationally where their financial incentives and the assessment of their health care needs are involved.

Beyond this, we've assumed that for some people there may be a "gray area", who would only have a small incentive to not purchase health insurance, where any benefit in doing so is not very large with respect to their household income, and where the decision to buy or not buy should instead be based upon an assessment of what the buyer's actual health care needs for their household will be in the near term, rather than purely upon its cost with respect to the ObamaCare income tax.

Mathematically, we've defined that gray area as being equal to the difference between the penalty tax they might choose to pay or an amount equal to 4.2% of their income before taxes, which closely corresponds to the average expenditure of U.S. households for health insurance in 2015 according to the most recent Consumer Expenditure Survey. This figure has increased from the 3.1% of income before taxes that was indicated by data in the Consumer Expenditure Survey report for 2012, which is a direct consequence of how the Affordable Care Act has sharply escalated the cost of health insurance in the United States since it became law.

Updates

Here at Political Calculations, our policy is for our tools to always improve over time. This section of this indicates all the significant changes we have made to the text of this article and the code for this tool.

- 20 September 2013: Modified programming to consider the tax exemption that might apply if the out-of-pocket cost of the least-expensive "Bronze" plan, even after the subsidy tax credit is considered, is still greater than 8% of their household income. Modified text in Assumptions section to indicate change was incorporated.

- 25 September 2013: Modified text in fourth paragraph to better clarify when an individual opting to pay the tax instead of a premium could acquire insurance if they determine they will need it. Added the Updates section to communicate all significant changes in this post and tool.

- 27 October 2013: Updated the data for Ohio, which will be expanding its Medicaid program, and also for Pennsylvania, which appears set to expand its Medicaid program to some degree.

- Updated 7 November 2015: Montana is now listed among the states expanding their Medicaid programs. We should also note that seven of the now 30 states that have adopted the Medicaid expansion are also imposing measures that will limit costs to the states, such as Montana's decision to require Medicaid beneficiaries earning above 100% of the federal poverty level to pay premiums equal to up to 2% of their annual income. Other states that have adopted cost control measures that have been approved by the federal government include Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, New Hampshire, and Pennsylvania.

- Updated 16 October 2016: Louisiana has expanded their Medicaid coverage under the federal plan, and both Indiana and New Hampshire have expanded their Medicaid coverage under an alternative plan with the adoption of cost control measures that have been approved by the federal government. We've also updated this version of the tool with 2016's poverty thresholds that hold for the 48 contiguous states, Alaska and Hawaii.

Legal Disclaimer

Materials on this website are published by Political Calculations to provide visitors with free information and insights regarding the incentives created by the laws and policies described. However, this website is not designed for the purpose of providing legal, medical or financial advice to individuals. Visitors should not rely upon information on this website as a substitute for personal legal, medical or financial advice. While we make every effort to provide accurate website information, laws can change and inaccuracies happen despite our best efforts. If you have an individual problem, you should seek advice from a licensed professional in your state, i.e., by a competent authority with specialized knowledge who can apply it to the particular circumstances of your case.

Labels: health, insurance, personal finance, risk, tool

Is there a better way to weight stocks within a market index?

Modern portfolio theory suggests that the optimal way to weight stocks within an index is according to their market capitalization, where the percentage representation of each company within a particular index is based on the product of its share prices and number of shares outstanding with respect to the total sum of all the market capitalizations of the companies whose stocks make up the index. Examples of market cap-weighted indices includes the S&P 500 and the Nasdaq 100 (Ticker: QQQQ).

There are, of course, other ways to weight the holdings of the stocks of individual companies within a market index. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (Ticker: DJI) is a price-weighted index. There are also equal weighted indices, in which the number of shares of each component stock within the index is periodically adjusted so that each represents the same market capitalization.

A little over 10 years ago however, Rob Arnott of Research Affiliates introduced a new method for setting the weight of each stock within a market index, called fundamental indexing. Here, instead of using either market cap or price, stocks within the index would be weighted according to fundamental measures of their companies' business performance, such as their revenue, dividend rates, or book values.

Here is the promise of fundamental indexing that Arnott noted back in 2006, based on his analysis of the 1,000 stocks that made up his proposed index:

How consistent is this approach? It's awfully consistent. During economic expansions, you add almost two percent a year. During recessions -- when you most need those returns -- you add three and a half percent. During bull markets you add 40 basis points. You don't really add anything in bull markets, because they are driven more by psychology than by the underlying fundamental realities of the companies. And so during bull markets you keep pace. Which is good; it's important. During bear markets you find yourself adding 600 to 700 basis points per annum. Bear markets are when reality sets in and people say, "Show me the numbers." Bear markets are when this really comes on strong. Also, during periods of rising rates, two and a half percent added. During periods of falling rates, one and a half percent added.

Soon, it became possible to invest in Arnott's new kind of index, where the first one was an Exchange Traded Fund based on his original 1,000 stocks, Powershares RAFI US 1000 ETF (NYSE: PRF). The follwwing chart compares the relative performance of the fundamentally weighted PRF against the price weighted DJI and the market cap-weighted S&P 500 over its entire history.

In this chart, we see that through the close of trading last Friday, 14 October 2016, the relative value of the fundamentally weighted PRF was up by 84.15% over its initial 30 December 2005 value, while the Dow Jones Industrial Average was 66.78% higher and the S&P 500 was 68.15% higher.

But we also see that there were periods where DJI either outperformed or performed as well as PRF. We also noticed that most of the PRF's gains over the market cap-weighted S&P 500 came in 2009, so we wondered how the relative performance of the PRF has fared since that time. So, we reset the chart to show the relative performance of each major type of index to begin in January 2010. The next chart shows what we found.

We see that PRF has outperformed both the S&P 500 and DJI over the period covered in this chart, having risen to be 96.32% above its 8 January 2010 level, compared to the S&P 500's 93.48% and the DJI's comparatively lackluster 73.23%. Meanwhile, we also confirm that much of PRF's relative outperformance over the longer period of time with respect to the S&P 500 occurred as an almost singular event in mid-2009, when whatever factors boosted it also boosted the DJI.

What this outcome suggests is that the considerable outperformance of PRF during 2009 has not been replicated in the years since, where through 14 October 2016, it has largely found itself within spitting distance of the performance of the S&P 500.

And yet, the fundamentally weighted PRF has generally performed either equivalent to or slightly better than the market capitalization weighted S&P 500 over that time.

As an investment then, it has some very attractive qualities that suggest a place for it in one's long term holdings. However, the near-performance of PRF with either the DJI or the S&P 500 over shorter durations means that it will be important to consider other factors, such as transaction costs, when choosing between investing in these different kinds of indices.

On a final note, we've been wanting to get back to this particular investing topic for some time, where the last time we discussed it here was back in August 2006!

What can we say? Some of our analytical projects have very long development periods!

Labels: fundamental indexing, investing, SP 500

How well off are typical Americans today?

That's a difficult question to answer using conventional economic statistics like GDP, because over time, GDP has become an increasingly less representative measure of the quality of life that Americans enjoy. That discrepancy hasn't gone unnoticed, as 61% of the respondents to a survey at Debate.org to the question "Is GDP growth a good indicator of improving quality of life?" answered "No".

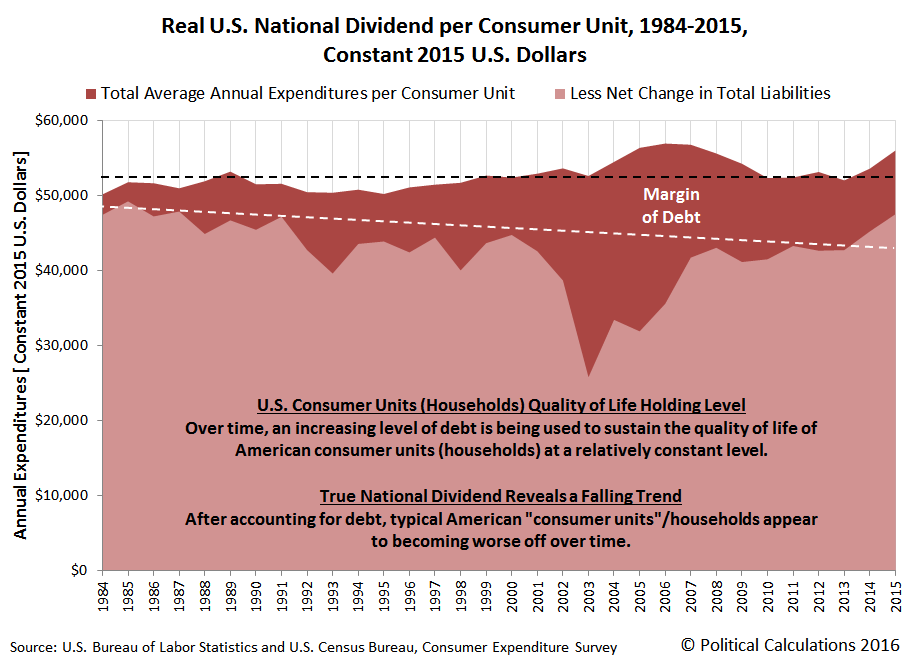

But there is an alternative. Last year, we realized that it is now possible to calculate Irving Fisher's consumption-based "national dividend" concept, which wasn't possible in 1906 when he proposed it or for much of the following eight decades, until the U.S. Census Bureau and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics began their annual survey of U.S. consumer expenditures at the household level in 1984.

We now have the ability to track the trends in the economic well-being of the average American "consumer unit", which consists of American families, single persons living alone or sharing a household with others but who are financially independent, or two or more persons living together who share expenses. The following chart shows the major trends for the nominal average expenditures of U.S. consumer units from 1984 through 2015.

In the chart, we've indicated both the total national dividend, which represents the average annual expenditures by U.S. consumer units/households and also what might be described as the "true" national dividend, which accounts for the average amount of that consumption that was financed by debt, and which should provide a good indication of degree to which Americans have sought to attain a particular level of quality of life today at the expense of impairing their quality of life tomorrow, as the bills for their total consumption come due.

We observe a generally rising trend in the nominal data for both the total national dividend and the true national dividend.

Let's next account for the effects of inflation over time. In the next chart, we've adjusted the nominal values for the national dividend per consumer unit/household for inflation as measured by the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers, so that they're expressed in terms of constant 2015 U.S. dollars. [On a side note, data from the Consumer Expenditure Survey is used to regularly revise and update the Consumer Price Index market basket of goods and services and their relative importance, which is why this measure of inflation is particularly relevant.]

In the inflation-adjusted chart, we see that since 1984, the total national dividend per typical American consumer units/households has been essentially flat. However, that outcome has been increasingly financed by debt, which we see in the falling trend for the true national dividend over time.

Since 2013, we see that there has been some improvement in both measures, where rising incomes have enabled increased consumption. In the next chart, we'll show the nearly one-to-one nominal relationship that exists between the average annual expenditures of U.S. consumer units and median household income.

The 2015 Consumer Expenditure Survey summarizes the major changes in how American consumer units/households spent their money from 2014 to 2015.

Personal insurance and pensions expenditures rose 10.9 percent to $6,349. This was primarily driven by the 11.4 percent increase in pensions and Social Security expenditures. In particular, non-payroll deposits to retirement plans, such as IRAs and Keoghs, rose 45.2 percent to $795 and payroll deductions for private pensions increased 25.2 percent to $645.

Education expenditures increased 6.4 percent. This was largely driven by a 63.7 percent increase in finance, late, and interest charges for student loans to $157.

Transportation expenditures increased 4.7 percent to $9,503. Within transportation, expenditures on vehicle purchases increased 21.1 percent, while spending on gasoline and motor oil declined 15.3 percent, continuing trends highlighted in the 2014-15 midyear report.

Expenditures on cash contributions reversed their 2013 and 2014 declines, increasing by 1.7 percent.

Expenditures on the discretionary categories of food away from home and entertainment continued increasing in 2015, up 7.9 percent and 4.2 percent respectively, after increasing 6.2 percent and 9.9 percent in 2014.

In 2014, health insurance saw the largest year over year increase in where Americans spend their money, coinciding with the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and its sharp increase in health insurance premiums.

References

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau. Consumer Expenditure Survey. Total Average Annual Expenditures. 2015. [Online Database]. Accessed 16 October 2016.

U.S. Census Bureau. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance in the United States: 2014 (P60-252). Current Population Survey. Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC). Table H-5. Race and Hispanic Origin of Householder -- Households by Median and Mean Income. [https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/cps/tables/time-series/historical-income-households/h05.xls]. 16 September 2016. Accessed 16 October 2016. [Note: Median incomes for 2013 and 2014 were revised with respect to values reported in previous years.]

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index - All Urban Consumers (CPI-U), All Items, All Cities, Non-Seasonally Adjusted. CPI Detailed Report Tables. Table 24. [Online Database]. Accessed 16 October 2016.

Labels: data visualization, economics

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.