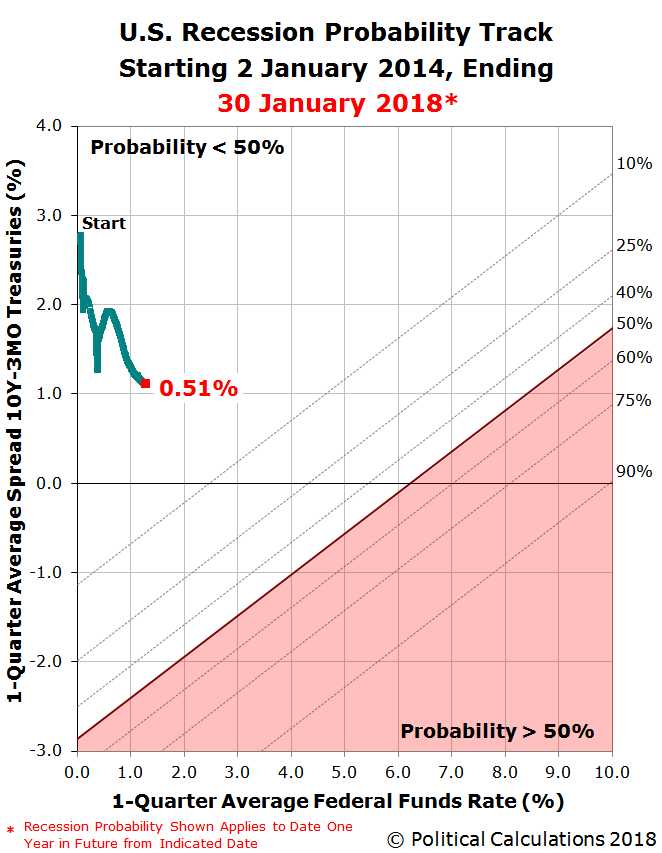

The risk of a national recession beginning in the United States anytime in the next year, or specifically between 30 January 2018 and 30 January 2019, is slightly over 0.5%. That value is about a tenth of a percentage point higher than our previous report on the topic about a month and a half ago.

Normally, we would have waited until after the Fed completed its end-of-January meeting before updating our recession probability track, but we decided to jump the gun given the sudden increase in volatility in the U.S. stock market, which is in part tied to rising yields for U.S. Treasuries.

Rising bond yields are starting to compete with stocks that pay some of the biggest dividends, leaving these companies behind even as the stock market has rallied to new highs.

The S&P utilities sector is down about 10% since the end of November and the real-estate sector has fallen 4.9%, sharply underperforming the S&P 500’s 6.6% rise. Companies in both groupings typically pay out big dividends relative to their stock prices, giving them high dividend yields.

For years, investors poured money into high-dividend stocks as they sought investment income that outpaced superlow yields in the bond market, which were held down by the Federal Reserve’s low-rate policy. But the central bank is reversing course, leading to a rise in bond yields that has accelerated in recent days.

The interesting thing about what's happening in the bond market is that long-term yields are increasing faster than short term yields, where the spread between the 10-Year and 3-Month constant maturity Treasury yields bottomed at 0.98% on 27 December 2017. Since then, the spread between the two Treasuries has opened up to 1.29%.

For our recession probability track, that means momentum has been building for a potential reversal in the downward component of its trajectory toward increased odds of recession.

That change will take some time to show up in the chart, where we're showing the trailing quarter average values for both the spread between the 10-Year and 3-Month Treasuries and the Federal Funds Rate. Meanwhile, the Fed is currently expected to increase the Federal Funds Rate by a quarter percentage point in March, then again in June and again in December 2018, so we would expect see the rightward component of its trajectory continue.

The Fed's hiking should also increase the yields of the 3-Month Treasury faster than longer-term Treasuries, so it's quite possible that the Fed's rate hiking will contribute to shrinking the size of the spread between long-term and short-term Treasury yields, offsetting the growing spread between the two in today's bond markets. At the very least, we'll have an interesting dynamic to watch to see which forces are winning out at any given point of time.

Fortunately, as it appears today, there is currently minimal risk that the National Bureau of Economic Research will someday declare that a national recession began in the U.S. between now and 30 January 2019 according to Jonathan Wright's recession forecasting methods, which provides the basis behind our recession probability track.

Previously on Political Calculations

- The Return of the Recession Probability Track

- U.S. Recession Probability Low After Fed's July 2017 Meeting

- U.S. Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up After Fed Does Nothing

- Déjà Vu All Over Again for U.S. Recession Probability

- Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up as Fed Hikes

Labels: recession forecast

Based on final figures for January through October 2017, and preliminary estimates for November through December 2017, the city of Philadelphia is set to fall nearly 15% short of its $92.4 million revenue target for the first full year of its controversial soda tax.

Overall, Philadelphia is set to collect $78.8 million from its 1.5 cents-per-ounce tax imposed on all pre-mixed naturally and artificially-sweetened beverages, including regular and diet drinks, distributed for retail sale within the city during 2017, which will fall $13.6 million short of the city's planned $92.4 million of revenue from the new tax.

That kind of a miss will have an impact on how much money is available to support the spending that Philadelphia city officials had planned for the proceeds of its soda tax. The following chart shows how the city had planned to spend the money it expected from its tax on sweetened drinks from Fiscal 2017 through 2021.

Instead, if the city's projected beverage tax revenue of $78.8 million represents the amount of money that it will be capable of collecting from the tax, the city can expect to only have $349.3 million to spend from 2017 through 2021, falling $60.3 million short of the $409.6 million that city officials planned they would be able to spend.

Philadelphia's city leaders will now have to make some choices. They can divert the revenue from other city taxes to make up the soda tax revenue shortfall so that they can still spend the same amount on the things they promised to Philadelphia's residents, or they can hike taxes to make up the difference, or they could cut their desired spending down to levels that they can actually support using revenue from Philadelphia's soda tax, or they could try to make up the gap by borrowing more money. And quite possibly, they could try some combination of all of these strategies.

Regardless, whatever they choose will come with a cost. The following chart shows how much the city's planned spending from Fiscal 2017 through 2024 would change if each category was reduced by an equal percentage to match the city's actual soda tax revenue in 2017, should Philadelphia's city leaders choose to follow a path of fiscal responsibility by not raising or diverting taxes or borrowing new funds.

The real question now is which interest groups within the city will be the designated losers for addressing the soda tax shortfall in what Philadelphia's city officials will decide to do. The city will revisit its spending plans in March 2018.

If Philadelphia's leaders were smart, they've been planning how they'll respond to the funding shortfall since January 2017, when the city's soda tax collections first fell below desired levels. At no time in 2017 did the city ever collect what it would have needed in any given month to hit its $92.4 million target to sustain their desired level of spending, so there's really no excuse for not having such a plan ready to go.

It was a week that started with 40% of the employees of U.S. government, the nonessential ones, enjoying a long three-day weekend off work, and ended with a bang, where a combination of unexpectedly strong earnings announcements and the confirmation that stock owners will benefit from the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 through significant dividend increases and the strong pursuit of organic growth opportunities led the S&P 500 to continue its now four-week long surge to unprecedented heights in the fourth week of January 2018.

We believe that investors are continuing to focus on 2018-Q4 in setting current day stock prices, which is happening as their focus on the likely actions by the Fed to hike short term interest rates by a quarter point each in March, June and again in December 2018 is taking something of a back seat to the earnings/tax cut related bonanza currently unfolding in U.S. stock markets. The following table updates the expectations for Fed rate hikes at different points in 2018.

| Probabilities for Target Federal Funds Rate at Selected Upcoming Fed Meeting Dates (CME FedWatch on 26 January 2018) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOMC Meeting Date | Current | |||||

| 125-150 bps | 150-175 bps | 175-200 bps | 200-225 bps | 225-250 bps | 250-275 bps | |

| 12-Mar-2018 (2018-Q1) | 21.6% | 75.2% | 3.2% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 13-Jun-2018 (2018-Q2) | 5.3% | 34.4% | 56.8% | 3.5% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 26-Sep-2018 (2018-Q3) | 1.7% | 14.5% | 39.9% | 37.9% | 5.8% | 0.3% |

| 19-Dec-2018 (2018-Q4) | 1.1% | 9.4% | 29.5% | 37.7% | 18.4% | 3.6% |

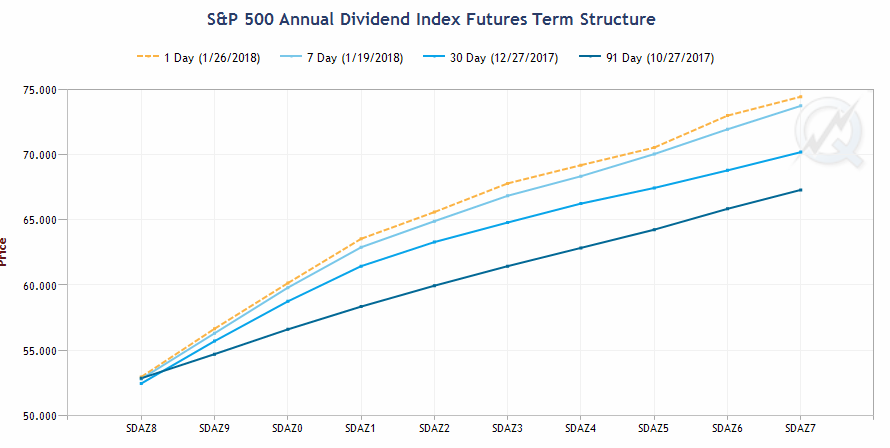

Speaking of future expectations, we are coming to suspect that the CME Group's S&P 500 quarterly dividend futures may be having something of a reporting glitch, where the projected values for future quarterly dividends per share haven't changed since 19 December 2017. That lack of response differs from what has been happening in the CME Group's Annual Dividend Index Futures, which has been showing some pretty impressive changes over the last month in what is expected for future S&P 500's annual dividends per share payouts from December 2018 through December 2027.

For a week with seeming so much going on, there wasn't much in the headlines that attracted our attention. Mostly, that's due to a news blackout by Fed officials in advance of their meeting next week, where the Fed's minions are blissfully required to hold their tongues, but otherwise, what news there was was positive for investors, with the exception of housing....

- Monday, 22 January 2018

- Oil rises on economic growth, OPEC/Russian supply curbs

- Before the market open: Markets brush off U.S. government shutdowns

- After the market close: Stocks hit record as senators reach deal to end shutdown (really though, almost nobody outside of Washington D.C. noticed the shutdown!)

- Tuesday, 23 January 2018

- Oil jumps as Brent tops $70, with inventory data on tap

- Senate confirms Jerome Powell as Federal Reserve chair

- Fed nominee Goodfriend, fan of negative rates, could roil debate

- Fed nominee Goodfriend: Current Fed policy 'more or less' on right course

- Netflix lifts S&P, Nasdaq; J&J, Procter hold Dow in check

- Wednesday, 24 January 2018

- Thursday, 25 January 2018

- Friday, 26 January 2018

Barry Ritholtz sets out the positives and negatives for the U.S. economy and markets that he saw in Week 4 of January 2018.

If you listen closely, you'll hear the Cantina theme from Star Wars, as Dani Ochoa scrawls out a rather interesting equation....

We came across the video above via c|net, but if you'd prefer the original without the musical overlay, here's the link. (She also has a rendition of the Imperial March!)

Labels: math

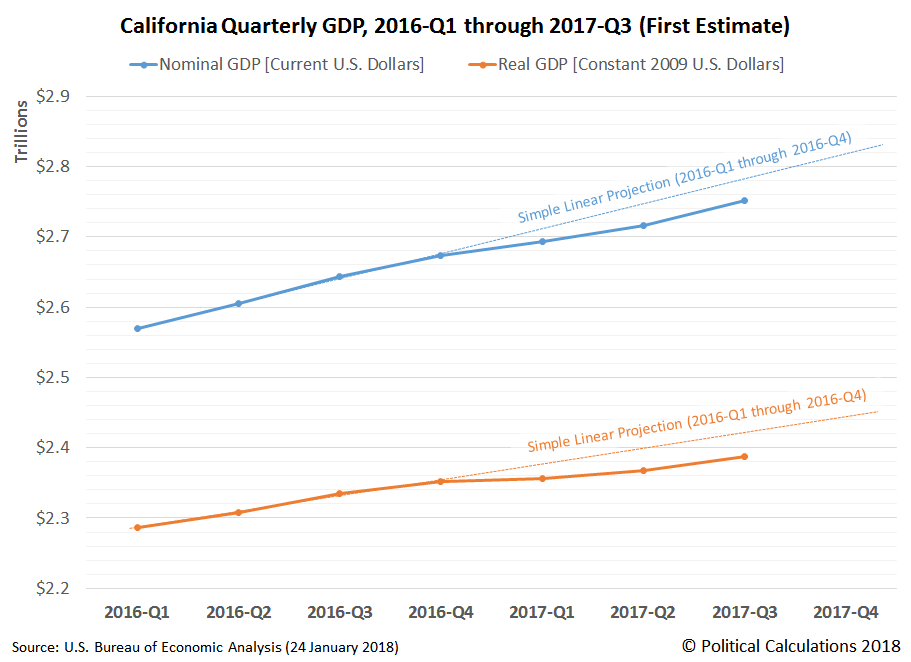

California's economy took a pretty big hit in 2017. Specifically, it appears to have taken a pretty big hit in the first quarter of the year, after which it appears to have slowly recovered at real growth rates that are slower than what the domestic U.S. economy has seen as a whole. The following chart shows the BEA's estimated GDP for California in the period from the first quarter of 2016 through the just-released preliminary data for the third quarter of 2017.

In the chart above, we've used simple linear projections to illustrate the extent to which California's nominal and inflation-adjusted gross domestic products in 2017 are falling below their 2016 trends. Although the slowing trend really began in 2016-Q4, as you can see, most of that gap between previous trend and actual performance opened up in 2017-Q1, when California's economy appears to have stagnated. Since then, the gap has continued to persist through 2017-Q3, even as the state's economic growth rate has rebounded.

Drilling down into the state level GDP data, we find that the most negatively affected industries in California in 2017-Q1 was its agricultural sector, followed by its finance and insurance industry, neither of which have recovered to the levels they were at the end of 2016. The same holds true to a lesser extent for the state's mining, construction, manufacturing and utility industries, which have also seen recessionary conditions in 2017. The state's manufacturing and finance and insurance industries have shown some signs of recovery in 2017-Q3.

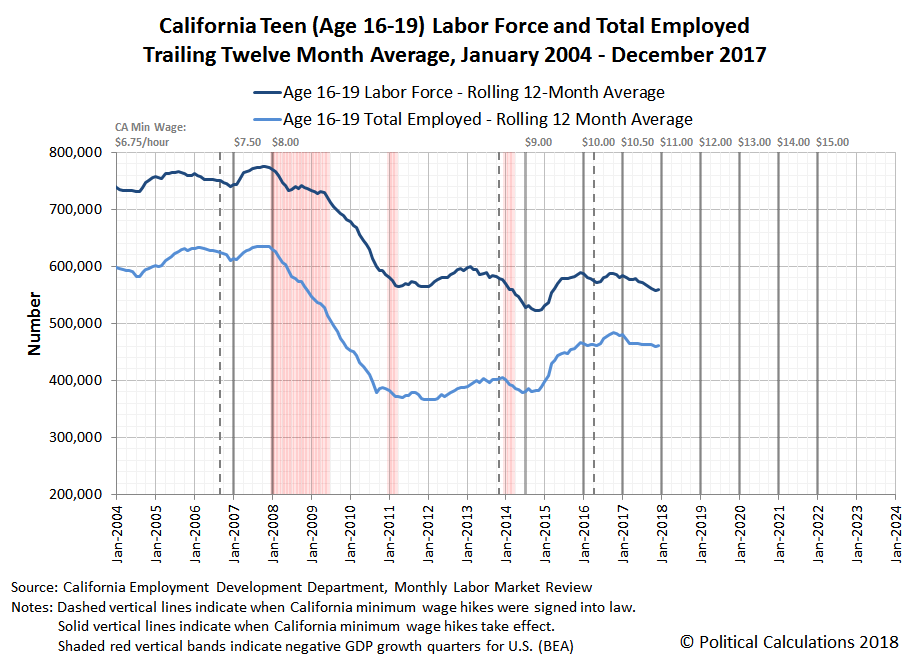

Since the BEA's regional GDP data lags the current day by nearly four months, state officials seeking to respond in a timely manner to unexpected changes in the state's economy without foolishly waiting months or years for data revisions to be produced, as some isolated academics with little-to-no real world leadership experience might desire, can use the state's monthly employment data to get a more real-time picture of the state's economic situation in order to determine what actions they might need to take to avoid allowing any developing problems to needlessly escalate. The following charts show California's trailing twelve month average labor force and employment levels as reported by the state's Employment Development Department, which shows the trends for both from January 2004 through December 2017. This is the same household employment data that was available to California state officials in near-real time over this whole period - judge for yourself whether it provides actionable information, or more simply, whether it affirms or contradicts the picture being painted by the state's more slowly emerging GDP data.

In this second chart, we see that the growth of the size of California's labor force has been mostly stagnant in 2017. However, we see that after having been stagnant for most of 2017, the state's total employment level has picked up, particularly in the last three months of the year. Most of those increased number of jobs however appear to mostly be catching up with increases in California's population, where the state's labor force-to-population ratio shows a small decline, while the state's employment-to-population ratio has begun to recover after having declined into the third quarter of 2017. The overall effect for 2017 is flat however, as California's December 2017's employment-to-population ratio of 59.2% is the same as it was in January 2017.

Since this data is drawn from the California EDD's monthly report on California's demographic labor force, we can confirm that almost all of the improvement in the employment level is in the state's adult (Age 20+) population. California's teenagers are seeing a more dismal version of the state's employment situation, as can be seen in the following chart.

This chart also illustrates the value of data from the household employment survey, which we can observe in what the teen employment data was screaming about the state of California's economy as early as January 2008 at the start of the so-called Great Recession. It wasn't until December of that year that the National Bureau of Economic Research confirmed that the nation was in a period of economic contraction that began in that month, following the peak of the previous period of expansion in December 2007. This sort of information was simply not visible for a prolonged period of time in the establishment survey employment data preferred by those with irrational fears of measurement errors in the household survey data.

We anticipate that the employment situation for California's teens will be an interesting story to follow in 2018. Typically, this portion of California's labor force has borne the brunt of the state's series of higher-than-federal minimum wage increases, which has harmed the employment prospects for this least educated, least skilled and least experienced portion of California's labor force. However, in 2018, the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act has permanently reduced the burden of federal corporate income taxes on businesses, where many will have more money available to pay higher wages to their employees, including those mandated by state and local governments, without necessarily forcing cuts elsewhere in their operations.

2018 could then be a year where the prospects for teen employment in a state that is hiking its minimum wage might improve, even in lackluster economic conditions, which would buck the typically negative pattern that we've seen whenever other mandated minimum wage hikes have taken effect without a similar corresponding boost to the cash position of businesses that employ minimum wage workers. We'll perhaps get to see how that might work in 2018!

Update 25 January 2018, 8:56 PM EST: Made some minor word changes to improve the overall flow of readability and added some badly needed punctuation. We've also seen in our site traffic that a very isolated academic who is still really upset that we exposed their campaign of pseudoscience two years ago as part of our Examples of Junk Science series is getting worked up again, so if you came here by way of their site, please be aware that they're engaged in an ongoing campaign of retaliation, somewhat like the one featured in this example from our series.

Labels: data visualization, economics

As a general rule, we don't often comment on individual stocks, much less forecast their likely trajectory, the way we do with the S&P 500. When we do, it is often because we've picked up on something interesting or contrary about the stock in question.

That was the case just over two months ago, when we focused rather specifically on the situation of General Electric (NYSE: GE), where we indicated that the company's stock price "had further to fall", even after the company had just announced that it would slash its dividends per share in half.

At the time, GE was trading at $18 per share, where we initially anticipated that it would fall to trade within a range between $14 and $16 per share. Just a few days later, after doing a more refined analysis incorporating more historic data points defining the relationship between the company's share price and its expected forward twelve month dividends per share, we revised that target range to be slightly higher, where we projected that GE's share price would drop to be somewhere between $15 and $17 per share.

Two months later, despite having benefited from the general market exuberance associated with the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 in the meantime, our revised projection for the future of GE's stock price has come to pass, allowing us to close the window on what we had predicted would happen in the "near future".

The proximate cause for GE's sudden decline in fortune into our projected target range during the last week was the revelation that the company would have to take a significant charge to its books from an old venture where the company's insurance division issued long-term care policies where the company underestimate its risk of negative exposure. Although the company stopped issuing new policies years ago, new claims against its existing portfolio will drain cash that the company doesn't have, even after the passage of permanent corporate tax rate cuts in the U.S.

GE's new CEO, John Flannery, has also raised the possibility that the industrial conglomerate will split itself into several different, independent companies as part of its overall restructuring.

There is a very high likelihood then that GE, as we have known it, has itself come to pass. Its future now very much hinges on how much traction that Flannery can get in turning around GE's fall as a whole, and whether or not he can avoid having to divvy up what remains of what once was one of the biggest of all the blue chips in the U.S. stock market, if not the world.

Update 7:40 AM EST: GE's earnings are out - in 2017-Q4, the company's revenue dropped by 5% from the previous quarter, driving a $10 billion loss. There was some good news however, as GE generated more cash ($7.8 billion) from its operating activities than had been expected ($7 billion).

It's the kind of report that is driving schizophrenia over at The Street, which featured the following two stories (or updates) this morning:

- Nasty General Electric Stock Selloff Likely Has Further to Go: Chart

- Here's Why GE Stock Surprisingly Is Rising After Weak Earnings

The company will be having a conference call with investors at 8:30 AM EST this morning.

Update 11:08 AM EST: Well, an SEC investigation can certainly take some of the wind out of a stock price's sails!

Labels: data visualization, dividends, forecasting, stock market

When a scientist realizes that they've made a fundamental error in their research that has the potential to invalidate their findings, they are often confronted with an ethical dilemma in determining what course of action that they might take to address the situation. Richard Mann, a young researcher from Uppsala University, lived through that scenario back in 2012, when a colleague contacted him right before he presented a lecture based on the results of his research that he had a problem that called his results into question.

When he gave his seminar, Mann marked the slides displaying his questionable results with the words "caution, possibly invalid". But he was still not convinced that a full retraction of his paper, published in Plos Computational Biology, was necessary, and he spent the next few weeks debating whether he could simply correct his mistake with a new analysis rather than retract the paper.

But after about a month, he came to see that a full retraction was the better option as it was going to take him at least six months to wade through the mess that the faulty analysis had created. However, it had occurred to him that there was a third option: to keep quiet about his mistake and hope that no one noticed it.

After numerous sleepless nights grappling with the ethics of such silence, he eventually plumped for retraction. And looking back, it is easy to say that he made the right choice, he remarks. "But I would be amazed if people in that situation genuinely do not have thoughts about [keeping quiet]. I had first, second and third thoughts." It was his longing to be able to sleep properly again that convinced him to stay on the ethical path, he adds.

Mann's case represents a success story for ethics in science, where his choices to demonstrate personal integrity and to provide transparency regarding the errors he had made through the retraction of his work proved to have no impact on his professional career, though he may have feared it. Such are the rewards of integrity and transparency in science, where the honest pursuit of truth outweighs both personal reputation and professional standing.

Still, an 2017 anonymous straw poll of 220 scientists indicated that 5% would choose to do nothing if they detected an error in their own work after it had been published in a high-impact journal, where they would hope that none of their peers would ever notice, while another 9% would only retract a paper if another researcher had specifically identified their error.

According to Nature, only a tiny fraction of published papers are ever retracted, even though a considerably higher percentage of scientists have admitted to knowing of issues that would potentially invalidate their published results in confidential surveys.

The reasons behind the rise in retractions are still unclear. "I don't think that there is suddenly a boom in the production of fraudulent or erroneous work," says John Ioannidis, a professor of health policy at Stanford University School of Medicine in California, who has spent much of his career tracking how medical science produces flawed results.

In surveys, around 1–2% of scientists admit to having fabricated, falsified or modified data or results at least once (D. Fanelli PLoS ONE 4, e5738; 2009). But over the past decade, retraction notices for published papers have increased from 0.001% of the total to only about 0.02%. And, Ioannidis says, that subset of papers is "the tip of the iceberg" — too small and fragmentary for any useful conclusions to be drawn about the overall rates of sloppiness or misconduct.

There is, of course, a difference between errors resulting from what Ioannidis calles "sloppiness", which can run the gamut from data measurement errors to the use of less-than-optimal analytical methods, which can all happen to honest researchers, and those that get baked into research findings through knowing misconduct.

The good news is that for honest scientists who act to disclose errors in their work, there is no career penalty. And why should there be? They are making science work the way that it should, where they are contributing to the advancement of their field where the communication of what works and what doesn't work has value. As serial entrepreneur James Altucher has said, "honesty is the fastest way to prevent a mistake from turning into a failure."

The bigger problem is posed by those individuals who put other goals ahead of honesty. The ones who choose to remain silent when they know their findings will fail to stand up to serious scrutiny. Or worse, the ones who choose to engage in irrational, hateful attacks against the individuals who detect and report their scientific misconduct as a means to distract attention away from it, which is another form of refusing to acknowledge the errors in their work.

The latter population are known as pseudoscientists. Fortunately, they're a very small minority, but unfortunately, they create outsized problems within their fields of study, where they can continue to do damage until they're exposed and isolated.

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: ethics, junk science, management, quality

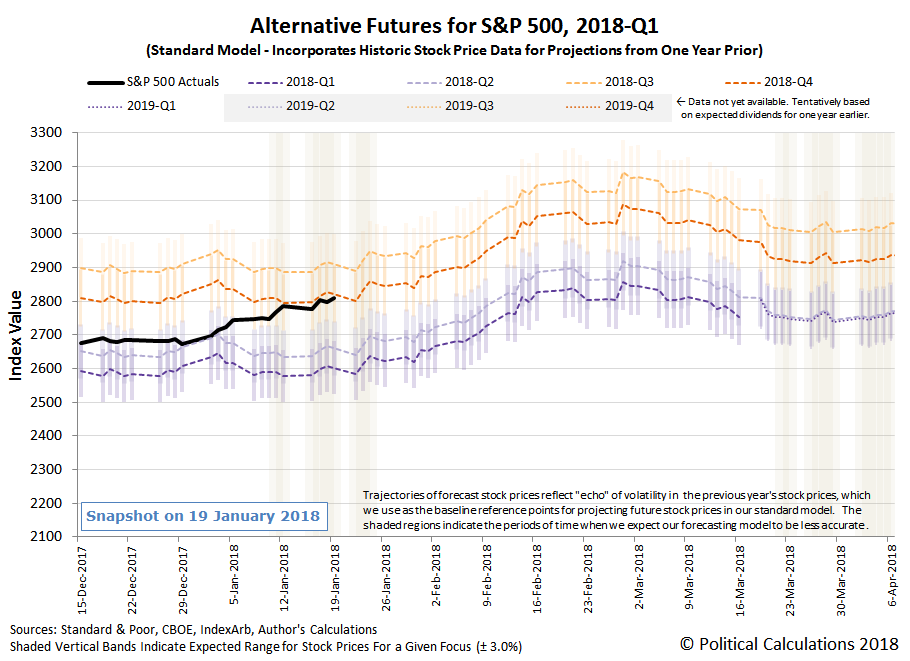

Wall Street certainly didn't have much in the way of negative thoughts with respect to the prospects for a federal government shut down last week. Even though White House Office of Management and Budget and interim Consumer Finance Protection Bureau director Mick Mulvaney gave a "between 50 and 60 percent" chance that the U.S. Congress would fail to reach an agreement to keep the entire government open as a legislative deadline neared, which was widely known well before the market closed, U.S. stock prices went on to close on Friday, 19 January 2018 at their highest level ever.

That's largely because where investors are concerned, politicians do little more than offer noisy distraction. Except for those very rare times where they might do something that actually affects the interests of investors, such as changing tax laws, it just isn't worth taking the time and energy to pay much attention to the things that grandstanding politicians say. Particularly where federal government shutdowns are concerned, seeing as there have now been no fewer than 19 since the passage of the 1974 Congressional Budget and Impoundment Control Act, which has made shutdowns like this latest one a recurring feature of how elected politicians choose to manage the U.S. government.

As for what things do attract the attention of investors, the trajectory of stock prices during Week 3 of January 2018 suggests that they are presently focusing much of their attention on 2018-Q4 and the expectations associated with that distant future quarter. Previously, we had thought investors might be splitting their focus between 2018-Q1 and 2018-Q3, but with the probability of a Fed rate hike occurring in 2018-Q3 now seemingly a low probability event, a shift in investor focus to 2018-Q4 appears to be a better explanation for what we're observing.

We should also note that the accuracy of our dividend futures-based model's projections are currently being affected by the echo effect from the past volatility of stock prices, which arises as a result of our model's use of historic stock prices as the base reference points for making its projections of the future. Here, since the magnitude of the current echo is relatively low, our model's projections for all alternative futures for the period from 11 January through 24 January 2018 are slightly understated from what they would be if no echo effect were present in the projections.

Taking that small understatement into account along with what we know about how far forward in time investors are looking, we find that the S&P 500 is tracking along the lower end of the range that we would expect they would if investors were closely focused on 2018-Q4 in setting today's stock prices, which frankly is not much different from what the unadjusted chart above indicates. To the extent that investors solidify their attention on 2018-Q4, we may have come to the end of the Lévy flight event that characterized the movement of U.S. stock prices during the first two weeks of 2018.

Regardless, outside of the better-than-even odds that the U.S. government would need to shut down a portion of its operations after Friday, 19 January 2018, there wasn't much notable in the news headlines of the third week of January 2018.

- Tuesday, 16 January 2018

- Wednesday, 17 January 2018

- Thursday, 18 January 2018

- Friday, 19 January 2018

The Big Picture's weekly listing of all the positives and negatives that Barry Ritholtz saw for the U.S. economy and markets in the holiday-shortened third week of January 2018 is up!

One week ago, the Wall Street Journal broke the news that the World Bank had a serious problem with one of its most popular and useful products, its annual Doing Business index.

The World Bank repeatedly changed the methodology of one of its flagship economic reports over several years in ways it now says were unfair and misleading.

The World Bank’s chief economist, Paul Romer, told The Wall Street Journal on Friday he would correct and recalculate national rankings of business competitiveness in the report called “Doing Business” going back at least four years.

The revisions could be particularly relevant to Chile, whose standings have been volatile in recent years—and potentially tainted by political motivations of World Bank staff, Mr. Romer said.

The report is one of the most visible World Bank initiatives, ranking countries around the world by the competitiveness of their business environment. Countries compete against each other to improve their standings, and the report draws extensive international media coverage.

In the days since, Romer has clarified that he doesn't believe that the World Bank staff engaged in a politically-motivated strategy aimed at disadvantaging Chile's position within its annual rankings, but instead failed to adequately explain how changes that the World Bank's staff made in updating their methodology of its Doing Business index affected Chile's position within the rankings from year to year.

Looking at the controversy from the outside, we can see why a political bias on the part of the World Bank's staff might be suspected, where positive and negative changes in Chile's position within the annual rankings coincided with changes in the occupancy of Chile's presidential palace.

That's why we appreciate Romer's willingness to openly discuss the methods and issues with communication, including his own, that have contributed to the situation. In time, thanks to the demonstrations of integrity and transparency that Romer is providing today as the staff of the World Bank works to resolve the issues that have been raised, the people who look to the Doing Business product will be able to have confidence in its quality. That will be the reward of demonstrating integrity and providing full transparency during a pretty mild version of an international public relations crisis.

Update 27 January 2018: Perhaps not as mild an international public relations crisis as we described. Paul Romer has stepped down as Chief Economist at the World Bank. This action is likely a consequence of the damage to the World Bank's reputation that arose from his original comments to the Wall Street Journal suggesting that political bias may have intruded into the Doing Business rankings to Chile's detriment.

Analysis: The problem for the World Bank now is that the issues that Romer identified with its methodology for producing the Doing Business index predate his tenure at the institution. How the World Bank addresses those issues will be subject to considerable scrutiny, where the institution will still need to provide full transparency into its methods for producing the index in order to restore confidence in its analytical practices. Without that kind of transparency, the issues that Romer raised, including the potential for political bias that Romer indicates he incorrectly stated, will not go away.

Not every matter involving correcting the record has the worldwide visibility of what is happening at the World Bank. We can find similar demonstrations of the benefits of integrity and transparency at a much smaller scale, where we only have to go back a couple of weeks to find an example. Economist John Cochrane made a logical mistake in arguing that property taxes are progressive, which is to say that people who earn higher annual incomes pay higher property taxes than people who earn lower annual incomes.

In search of support for his argument, he requested pointers to data indicating property taxes paid by income level from his readers, who responded with results that directly contradicted his argument. How he handled the contradiction demonstrates considerable integrity.

Every now again in writing a blog one puts down an idea that is not only wrong, but pretty obviously wrong if one had stopped to think about 10 minutes about it. So it is with the idea I floated on my last post that property taxes are progressive.

Morris Davis sends along the following data from the current population survey.

No, Martha (John) property taxes are not progressive, and they're not even flat, and not even in California where there is such a thing as a $10 million dollar house. (In other states you might be pressed to spend that much money even if you could.) People with lower incomes spend a larger fraction of income on housing, and so pay more property taxes as a function of income. Mo says this fact is not commonly recognized when assessing the progressivity of taxes.

Not only is Cochrane providing insight into the error in his thinking, his transparency in addressing why it was incorrect is helping to advance the general knowledge of his readers.

In both these cases, we have examples of problems that could have been simply swept under a rug and virtually ignored with nobody being the wiser, but where the ethical standards of the people involved wouldn't let them do that. Even in making mistakes while addressing the mistakes they made or discovered, they made the problems known as they worked to resolve them, and because they did so, we can have greater confidence in trusting the overall quality of their work.

In the real world where people value honesty, admitting or acknowledging errors is no penalty. In fact, there are solid examples where scientists have retracted papers because of errors they made that, ultimately, had zero impact on their careers. Which in some cases, involved going on to be awarded Nobel prizes in their fields.

Retracting a paper is supposed to be a kiss of death to a career in science, right? Not if you think that winning a Nobel Prize is a mark of achievement, which pretty much everyone does.

Just ask Michael Rosbash, who shared the 2017 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for his work on circadian rhythms, aka the body's internal clock. Rosbash, of Brandeis University and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, retracted a paper in 2016 because the results couldn't be replicated. The researcher who couldn't replicate them? Michael Young, who shared the 2017 Nobel with Rosbash.

This wasn't a first. Harvard's Jack Szostak retracted a paper in 2009. Months later, he got that early morning call from the Nobel committee for his work. And he hasn't been afraid to correct the record since, either. In 2016, Szostak and his colleagues published a paper in Nature Chemistry that offered potentially breakthrough clues for how RNA might have preceded DNA as the key chemical of life on Earth - a possibility that has captivated and frustrated biologists for half a century. But when Tivoli Olsen, a researcher in Szostak's lab, repeated the experiments last year, she couldn't get the same results. The scientists had made a mistake interpreting their initial data. Once that realization settled in, they retracted the paper - a turn of events Szostak described as "definitely embarrassing."

What isn’t absurd is the idea that admitting mistakes shouldn’t be an indelible mark of Cain that kills your career.

Indeed it shouldn't. And for honest people with high standards of ethical integrity and a willingness to be transparent about the mistakes that they have made or that have occurred on their watch, it isn't.

Labels: ethics, junk science, management, quality

The relative period of order for the S&P 500 that began back on 31 March 2016 has come to an end.

The breakdown of order in the S&P 500 became clearly evident on 11 January 2018, when the level of the S&P 500 surged to be more than three standard deviations above the mean trend curve that has described the relationship between stock prices and their trailing year dividends per share since the end of the first quarter of 2016. Tracing this break in trend backwards to when it first took hold, we find that the last day that the previous period of relative order could be reasonably be said to have held is 29 December 2017, the last day of trading at the end of the fourth quarter of 2017, which is when stock prices were last within one standard deviation of the established mean trend curve.

That makes the explanation for what caused the break in order relatively easy to determine. We believe that it may be fully attributed to the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 on 22 December 2017, the provisions of which would take effect in 1 January 2018, to which investors would respond vigorously to their new incentives from the law beginning with the first day of trading in 2018 on 2 January 2018. It then took just eight trading days for the break in the previous period of relative order in the U.S. stock market to become definitive.

The new incentives for investors arise from the large and permanent reduction in corporate income tax rates, where investors may benefit by realizing larger dividend payments, by companies using their newly-freed funds to increase their productive investments, to lower their prices to consumers to gain market share, to better insulate themselves against having arbitrarily higher costs from government-mandated expenses imposed upon them (firms boosting the wages of their lowest paid employees can be said to be taking this action), or to simply use the opportunity of the newly-freed funds to improve their balance sheets. Or some combination of any or all of the above.

In a number of ways, the initial response of the stock market to the passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 is similar to what happened to stock prices following the passage of the Tax Relief Act of 1997, which caused the Dot Com stock market bubble to inflate. Unlike that event, where the differences in tax rates between dividends and capital gains changed the rate of return math for investors with dramatic and unstable effects upon stock prices, the changes that U.S. firms make in response to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 are much more likely to affect the fundamental expectations that investors have for their future business prospects, making a similar bubble unlikely.

No matter what, the U.S. stock market has entered into a very different period than it was before. How will that affect your investment decisions?

Labels: data visualization, dividends, SP 500

How much will your net take home pay change because of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 becoming law?

This is the third of three tools that we've built to do paycheck-related math in 2018, and is the only one that goes straight to the bottom line in showing how different your take home pay may be because of the new tax law. If you want greater detail into all the major parts of where your money goes in your paycheck, be sure to check out the previous two tools that we've developed:

- Your Paycheck in 2018, Before the Tax Cuts Kick In

- Your Paycheck in 2018, After the Tax Cuts Kick In

In this version, we've stripped down the inputs and outputs to just the bare essentials, just to get at the bottom line answer that many Americans are seeking. Please enter the indicated information into the table below, click "Calculate" to get your results, and hopefully, you'll be pleased by the results. [If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click through to our site to access a working version.]

Previously on Political Calculations

We've been in the business of calculating people's paychecks (not including state income tax withholding) since 2005!

- Your 2005 Paycheck

- Your 2006 Paycheck

- Your 2007 Paycheck

- Your 2008 Paycheck

- Your 2009 Paycheck

- Your Paycheck in 2010

- Your Paycheck in 2011

- Your Paycheck in 2012

- Your Paycheck in 2013: Part 1 - the "same as 2012" version.

- Your Paycheck in 2013: Part 2 - the "over the fiscal cliff" version.

- Your Paycheck in 2013: Part 3 - the "post-fiscal cliff deal" version.

- Your Paycheck in 2014

- Your Paycheck in 2015

- Your Paycheck in 2016

- Your Paycheck in 2017

- Your Paycheck in 2018, Before the Tax Cuts Kick In

- Your Paycheck in 2018, After the Tax Cuts Kick In

- The Bottom Line for Your 2018 Paycheck After the Tax Cuts

Labels: personal finance, taxes, tool

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.

![Desired Spending From Philadelphia Beverage Tax Revenue, Fiscal 2017 Through 2021 [Millions of Dollars] Desired Spending From Philadelphia Beverage Tax Revenue, Fiscal 2017 Through 2021 [Millions of Dollars]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEhcN8pManW9roFn3xj_bEHW8b4u_8m97s9XcYL9flN83KLqZD79lQSyl9BfYbl4IGqlV86fZkD-T2vgNcIL2xtCxY9vSH5QRVxzMXy1ZQNBq4qaqYe0vhctkTC84lj2yumC8Cn9/s1600/desired-spending-from-philadelphia-beverage-tax-revenue-fiscal-2017-through-2021.png)

![Projected Spending From Philadelphia Beverage Tax Revenue, Fiscal 2017 Through 2021 [Based on Actual 2017 Revenue] Projected Spending From Philadelphia Beverage Tax Revenue, Fiscal 2017 Through 2021 [Based on Actual 2017 Revenue]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjQezvLKMkM4k2nLT-6oR8n5SgczoYZf5FXR0DKuWrqZJRK0OMCGXO52NFDszhToQnSAXHINLcHKr3k3Ep_k83frbF42gthphKs6DXaqvfr8AIA2buKCmCndUz38d4OMHBpgWBx/s1600/projected-spending-from-philadelphia-beverage-tax-revenue-fiscal-2017-through-2021.png)