How on Earth did ancient alien theory get started?

In 2023, most Americans are well acquainted with the concept of aliens visiting Earth in the ancient past because of the influence of the Ancient Aliens television program that has aired almost continuously on the History Channel and other venues since 2010. Not to mention the decades of books, comics, movies, television shows and other entertainment vehicles that have made it part of the cultural zeitgeist in the 21st century. But despite the name, ancient alien theory has not been around forever and we think we can both describe how it came about and precisely date when it was first advanced.

We can do that by focusing on one of the basic claims that many ancient alien theorists make. In general, we can take the claim that aliens didn't just visit Earth in the past, but engaged in monumental activities that left their mark on the planet, and in particular, the claim that aliens contributed to the construction of the pyramids of Egypt.

To do that, we're going to use the tools of historiography, where we will identify the theories previous generations had about who built the pyramids.

Fortunately for us, we found numerous such theories neatly summarized within a book written by James Bonwick in 1877: The Great Pyramid of Giza: History and Speculation. Bonwick collected all the "facts and fancies" in circulation at the time about the pyramids in Egypt and included a whole chapter in his book dedicated to speculation and theories about who built them. Here are the main categories into which the thinking at that time fall, which we've organized from least to most probable according to what we know today:

- Yoingees, or rather, the earthbound losers of an ancient war with Hindu gods who somehow ended up in Egypt.

- Aryans. Because in 1877, of course.

- Biblical figures, which include:

- Jesus

- Various early descendants of Adam, also known as the "Adamites"

- Philistines and/or shepards

- Enslaved Israelites

- Egyptians acting under divine influence

- And, believe it or not, giants (put a pin here, it will come up later...)

- Finally, the Egyptians, directed by the pharaohs who ruled in that country for thousands of years.

The most important thing about this list that was produced at this point in history is that there is no hint of any theory involving the pyramids having been built by extraterrestrial beings. Ancient alien theory, as is popularly known today, did not exist. If it had, we have no doubt Bonwick would have at least given the idea equal billing with the Yoingees. But there are no mentions of little green or gray men, much less any discussion of strange visitors from the skies, stars, moons, or planets anywhere in Bonwick's text, so it's pretty safe to say that aliens themselves weren't a thing as Bonwick drafted the preface for his book on 28 August 1877 as it was about to be published.

However that was soon to change thanks to astronomical discoveries and how they were reported, particularly in the United States.

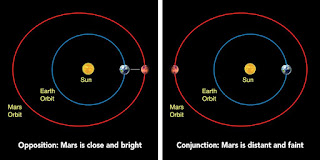

1877 was a big year for astronomy. That was the year the planet Mars was in a "Great Opposition" with Earth, which means it was as close to Earth as it gets at the same time it was as close to the Sun as it gets. That kind of astronomical alignment represents a big opportunity for astronomers, who took full advantage of it, pointing their newest and biggest telescopes toward the Red Planet in search of new discoveries.

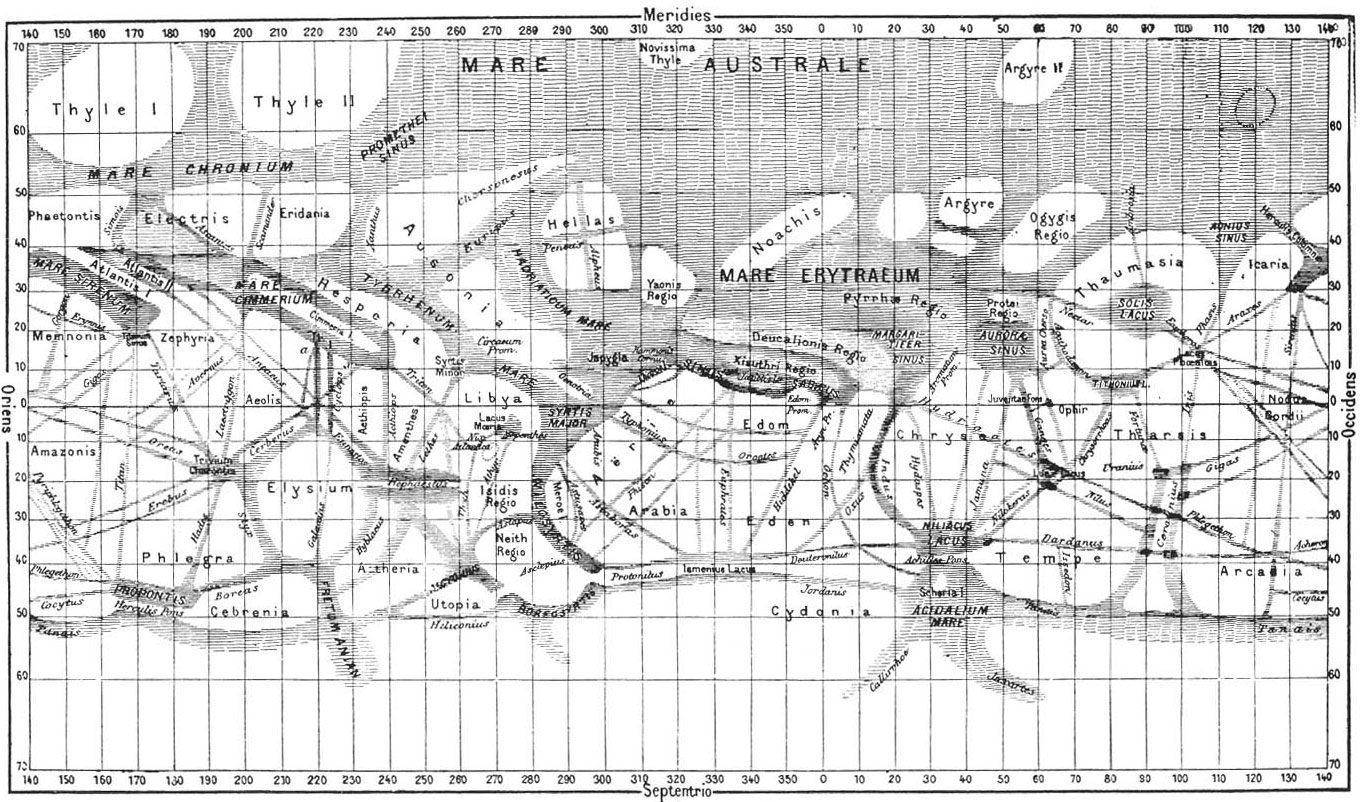

And big discoveries they made, including both of Mars' moons by U.S. astronomer Asaph Hall in August 1877! More significantly for our story, the period from autumn in 1877 through spring in 1878 is when Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli working at the Milan Observatory made the most detailed map of Mars yet. Schiaparelli's map identified dark areas as "mare" (seas) and light areas as continents on the Martian surface. He also drew a number of straight line features he saw on Mars' surface, calling them "canali", by which he meant naturally formed trenches or channels.

At this point, we'll interject to note that other astronomers later determined that Schiaparelli's "canali" features were really optical illusions, an artifact of the limitations of the telescope technology of the day. But that determination wasn't made until 1895, which gave a lot of time for speculation to build and get traction.

Because it goes around the sun faster than Mars, Earth will be in a regular opposition with Mars at approximately two year intervals, which sets the clock for what would happen. Schiaparelli continued refining his map during the next opposition of Mars from late 1879 to early 1880 and again in late 1881 to early 1882. This last opposition coincided with reports that other astronomers had confirmed his findings, which made his map of Mars very big news in early May 1882.

Very big news indeed, especially in English-language newspapers that translated "canali" as meaning "canals", which is where things really take off and the idea of alien beings from advanced civilizations became more than a rare literary device.

After the news of canals on Mars broke, each new opposition of Mars presented an opportunity for new speculations and claims to be made about intelligent life on that planet.

In 1884, French astronomer Camille Flammarion published a book hypothesizing life on other planets, including Mars. Two years after that, more astronomers claimed they had also seen Schiaparelli's canals and the idea of an intelligent canal-building race on Mars was given greater credibility. Skipping forward a couple of oppositions, updates to Schiaparelli's map in 1891 would reinforce the idea of Mars being inhabited by intelligent beings.

In the U.S., these developments inspired Percival Lowell, whose family had big money from the textile industry, to get into the astronomy game. In 1892, he started building an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona and began making his own Martian maps, which he would use to actively promote the idea. In 1894, Lowell speculated in a Boston magazine that intelligent life on Mars built the canals he was drawing on his maps. In 1895, Lowell put his reputation on the line as he published a series of articles in The Atlantic Monthly featuring his maps. He updated his maps again in 1897, showing hundreds of canals criss-crossing the surface of Mars.

That's when our story takes a deliberately fictional turn. 1897 is when H.G. Wells capitalized on the growing public excitement about the prospect of intelligent life on Mars and published The War of the Worlds in Pearson's Magazine in the United Kingdom and in The Cosmopolitan in the United States. The story ran in both outlets in serialized installments between April and December 1897. His story was the first to feature Martians, as an intelligent extraterrestrial race, traveling to Earth where they attacked and nearly destroyed human civilization before ultimately meeting their fate at the figurative hands of microscopic Earth germs.

The popularity and success of H.G. Wells' story led newspaper publishers to seek more stories like it, if not an outright sequel, to cash in on it. Wells himself had no interest in following up his story so newspaper publishers did the next best thing. They hired another author to write an unofficial, or really, an unauthorized sequel to The War of the Worlds.

That brings us to Garrett P. Serviss, who by some lights might be considered the late nineteenth century's equivalent of either Carl Sagan or Neil deGrasse Tyson for popularizing astronomy in the U.S.

In the 1890s, he was toiling away as an astronomy science writer and lecturer. As such, he would be up-to-date with nearly all these astronomical developments as he wrote columns for newspapers and magazines that were often syndicated. It was his connection with American newspaper publishers that soon presented him with a unique opportunity. Serviss was engaged to write their desired sequel the The War of the Worlds, which would start running within a matter of weeks after Wells' final installment of the War of the Worlds was published.

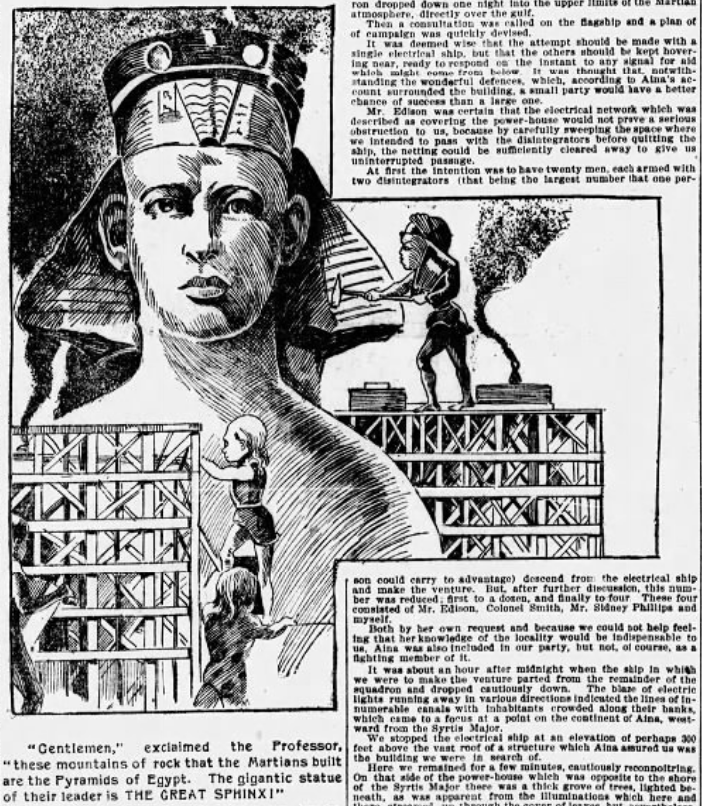

That sequel is Edison's Conquest of Mars, in which the famed American inventor would lead the world's greatest scientists and engineers on an interplanetary mission to strike back at the Martians. In terms of plot, it's kind of like a late 1800's version of The Avengers, but with a very different team of heroes. It was published as a syndicated series that appeared weekly in several large city U.S. newspapers from January through March 1898 and also went on to run in smaller newspaper markets later in the year.

In this scientific romance, as the earliest works of science fiction were called, Serviss brought together several key elements of what would become the basis of ancient alien theory for the first time, including:

- Percival Lowell's concept of an advanced Martian canal-building civilization,

- H.G. Wells' fiction involving Martians traveling to Earth, and

- the pre-1877 theory of giants, the ones mentioned in the Bible, building the pyramids.

All these things came together for the first time ever anywhere in the eighth installment of Edison's Conquest of Mars. In this part of the story, Serviss reveals the giant Martians he had previously introduced had traveled to Earth centuries earlier, where they built the pyramids. This installment of the story was published in newspapers like the San Francisco Examiner on Sunday, 20 March 1898. This installment incorporated some pretty spectacular artwork featuring Martians at work building the Egyptian Sphinx in the image of their leader:

Serviss' literary innovation combining these things together makes him the originator of all of today's "ancient alien" theories that involve extraterrestrials interacting with humans in the past and leaving behind evidence in the forms of monumental structures like the pyramids of Egypt.

The syndication of the installments of Edison's Conquest of Mars in newspapers across the U.S. gave the concept a wide introduction to the American people, and just like the clockwork speculation about life in Mars that built from 1877 through the late 1890s, provided the base for more speculations that have continued into the present day. The rest, as they say, is history.

Selected References

James Bonwick. The Great Pyramid of Giza: History and Speculation. New York: Dover Publications (2002). Originally published as Pyramid Facts and Fancies. London: C. Kegan Paul (1877). Preface written on August 28, 1877. pp 70-79.

Tabea Tietz. Giovanni Schiaparelli and the Martian Canals. SciHi Blog. March 14, 2019. [Online Article].

Percival Lowell. Four related essays from The Atlantic Monthly: "Mars. I. Atmosphere." vol. 75 (May 1895): 594-603; "Mars. II. The Water Problem." vol. 75 (June 1895): 749-758; "Mars. III. Canals." vol. 76 (July 1895): 106-119; "Mars. IV. Oases." vol. 76 (August 1895): 223-235.

Kevin Zahnle. Decline and Fall of the Martian Empire. Nature, 412, 209-2013 (2001). [Online article].

Garrett P. Serviss. Edison's Conquest of Mars. San Francisco Examiner, Sunday, 20 March 1898. p. 8. [Online scan at Newspapers.com].

Celebrating Political Calculations' Anniversary

Our anniversary posts typically represent the biggest ideas and celebration of the original work we develop here each year. Here are our landmark posts from previous years:

- A Year's Worth of Tools (2005) - we celebrated our first anniversary by listing all the tools we created in our first year. There were just 48 back then. Today, there are over 300....

- The S&P 500 At Your Fingertips (2006) - the most popular tool we've ever created, allowing users to calculate the rate of return for investments in the S&P 500, both with and without the effects of inflation, and with and without the reinvestment of dividends, between any two months since January 1871.

- The Sun, In the Center (2007) - we identify the primary driver of stock prices and describe a whole new way to visualize where they're going (especially in periods of order!)

- Acceleration, Amplification and Shifting Time (2008) - we apply elements of chaos theory to describe and predict how stock prices will change, even in periods of disorder.

- The Trigger Point for Taxes (2009) - we work out both when, and by how much, U.S. politicians are likely to change the top U.S. income tax rate. Sadly, events in recent years have proven us right.

- The Zero Deficit Line (2010) - a whole new way to find out how much federal government spending Americans can really afford and how much Americans cannot really afford!

- Can Increasing the Minimum Wage Boost GDP? (2011) - using data for teens and young adults spanning 1994 and 2010, not only do we demonstrate that increasing the minimum wage fails to increase GDP, we demonstrate that it reduces employment and increases income inequality as well!

- The Discovery of the Unseen (2012) - we go where so-called experts on income inequality fear to tread and reveal that U.S. household income inequality has increased over time mostly because more Americans live alone!

We marked our 2013 anniversary in three parts, since we were telling a story too big to be told in a single blog post! Here they are:

- The Major Trends in U.S. Income Inequality Since 1947 (2013, Part 1) - we revisit the U.S. Census Bureau's income inequality data for American individuals, families and households to see what it really tells us.

- The Widows Peak (2013, Part 2) - we identify when the dramatic increase in the number of Americans living alone really occurred and identify which Americans found themselves in that situation.

- The Men Who Weren't There (2013, Part 3) - our final anniversary post installment explores the lasting impact of the men who died in the service of their country in World War 2 and the hole in society that they left behind, which was felt decades later as the dramatic increase in income inequality for U.S. families and households.

Resuming our list of anniversary posts....

- The Toolmaker's Tool (2014) - we make the code we use for creating online tools available to all!

- Replacing GDP with the National Dividend (2015) - we explore our development of an alternative measure of economic welfare that can replace GDP.

- The Gamblers Who Invented Modern Encryption (2016) - we discover that a group of gamblers seeking to break the law in Missouri back in 1905 put together many of the elements that underlie secure electronic communications and financial transactions in 2016!

- The Isolation of El Niño (2017) - in which we advanced the development of a global economic indicator for Earth!

- Telescoping Median Household Income Back in Time (2018) - we find a way to nearly double the available supply of monthly median household income estimates with reasonable accuracy.

- Cashing Out of the S&P 500 (2019) - we develop a tool to answer the question of whether you can survive being retired if you're counting on cashing out your investment in the S&P 500!

- The Deadly Intersection of Anti-Police Protests and COVID-19 (2020) - it was the year of the coronavirus and political protests, so we combined the two in a way that only we could.

- The Birth of the Martian Economy (2021) - we don't mess around when we say we celebrate big ideas, and what's bigger idea to celebrate than the birth of an entire planet's economy?

- The S&P 500 Dividend Engine (2022) - we put the entire history of the S&P 500's cash dividends at your fingertips!

- The Origin of Ancient Alien Theory (2023) - how and when did the idea of aliens visiting Earth to do things like build pyramids get started?

Labels: ideas

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.