They're most likely reviewing comments on the Internet regarding today's advance release of GDP data for the first quarter of 2008, but following this recent Google search, we have to wonder if we might be doing their jobs for them? And if so, when do we start getting those juicy government paychecks?:

* Phonetic spelling - imagine a vendor at the ballpark yelling out our post title in the stands!

Labels: gdp forecast, none really

When we originally developed our two-quarter GDP bullet thermometer chart as a visual tool that we could use to better describe the overall health of the U.S. economy, we did so to address a deficiency that Bill Polley observed in the traditional definition of a recession as being a two-quarter period of negative GDP growth: those times when the GDP number bounces back and forth across the zero line between positive and negative territory.

Since our primary metric for GDP is the economic growth rate annualized over the previous two-quarter period, we automatically account for that situation. Using this two-quarter GDP growth rate, we can much more easily identify recessionary periods using just GDP data.

Then we went a step beyond that. We also incorporated David Tufte's GDP "grading scale" into our bullet chart visualization, which appears as the temperature scale gradients, but we did so in a way that would blend the transitions between otherwise distinct boundaries in that scale.

This blending effect allows us to account for something that's often missed in GDP reporting: the margin of error. We recognize that GDP figures are subject to revision, first in moving from the advance release for a given quarter, through the next preliminary release and then onto a "final" revision. And then, perhaps months or years later, the "final" revision for a quarter is perhaps revised again, as more economic data about the time becomes known. This blending allows for us to anticipate any potential downward revisions.

Today's advance release of GDP for the first quarter of 2008 (available in this PDF document) indicates that the U.S. economy is essentially on the edge of being in recession. With the two-quarter annualized GDP growth rate at 0.6%, it falls directly in the transition range between the "cold" purple zone indicating recession and the "cool" blue zone indicating slow growth:

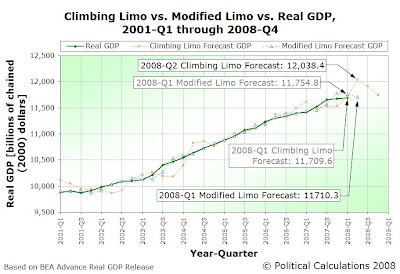

Eerily, at 0.6%, the GDP growth rate for 2008Q1 comes in right where both the Climbing Limo GDP forecasting method and our Modified Limo forecasting method would have placed it. The following chart shows where the advance release figure for 2008Q1 would be along with where both the Climbing and Modified Limo projection techniques anticipated it, along with the latest forecasts for each:

We would anticipate that the GDP figure for the second quarter of 2008 will come in between the forecast values for each of our Limo methods, however given the sharp rise and decline of the Climbing Limo forecast (which indicates changes in economic momentum), we would expect it to much more closely track the value for the Modified Limo forecast. At best, that would indicate that the U.S. economy is moving through a very slow growth period, edging the boundary of recession.

Bear in mind however that we will be revising this forecast twice more, as the 2008Q1 GDP data goes through it's preliminary and final revisions.

The 2008Q1 GDP Data Commented Upon Elsewhere

Greg Mankiw sees the glass half full and notes that Intrade's odds of recession in 2008 have dropped to 25% (although to be fair, the Intrade bet is whether there will be two consecutive quarters of negative growth!)

Barry Ritholtz is out of pocket at this writing, but will have comment soon, with a special focus upon corporate profits, the PCE inflation measure and seasonal adjustments.

Mark Perry makes the no recession call (yes, we hope he's ultimately right!)

Tom Blumer notes that the Democrats will have to put off their glee at being able to blame Bush for negative economic growth for at least another quarter.

Jim Hamilton has updated his Recession Indicator Index, which ticked up to 26.9% with the latest data. A reading of 65% is needed to anticipate the NBER's decision to declare 2008Q1 to have been in recession.

Bill Polley touches on the GDP report in providing an essential review of the Fed's action today, and also can claim bragging rights since his class correctly anticipated the Fed's action!

Finally, the WSJ surveys a number of institutional economists on their views of whether the economy is indeed in recession.

Labels: gdp, gdp forecast

If we were to scrap the excessively complex monstrosity that accurately describes the current version the U.S. income tax code and replace it with an income tax that actually makes sense for taxpayers and the government, how should that new income tax system work?

If we were to scrap the excessively complex monstrosity that accurately describes the current version the U.S. income tax code and replace it with an income tax that actually makes sense for taxpayers and the government, how should that new income tax system work?

Here at Political Calculations, unlike say, politicians, we solve problems. We study the failures of the past to understand how to avoid failures in the future. Better still, we seek to learn stuff from other people who have done this kind of research and put it to use in practical applications.

Where income taxes are concerned, our starting point for what they should look like begins with the Tax Foundation's Ten Principles of Sound Tax Policy, which we'll present below:

1. Transparency is a must. A good tax system requires informed taxpayers who understand how taxes are assessed, collected and complied with. It should be clear to taxpayers who and what is being taxed, and how tax burdens affect them and the economy.

2. Be neutral. The fundamental purpose of taxes is to raise necessary revenue for programs, not micromanage a complex market economy with subsidies and penalties. The tax system’s central aim should be to minimize distortions in the economy, and to interfere as little as possible with the decisions of free people in the marketplace.

3. Maintain a broad base. Taxes should be broadly based, allowing tax rates to be as low as possible at all points.

4. Keep it simple. The tax system should be as simple as possible, and should minimize gratuitous complexity. The cost of tax compliance is a real cost to society, and complex taxes create perverse incentives to shelter and disguise legitimately earned income.

5. Stability matters. Tax law should not change continuously, and tax changes should be permanent and not temporary. Instability in the tax system makes long-term planning difficult, and increases uncertainty in the economy.

6. No retroactivity. Changes in tax law should not be retroactive. As a matter of fairness, taxpayers should rely with confidence on the law as it exists when contracts are signed and transactions are made.

7. Keep tax burdens low. It makes a difference how large a share of national income is taken by government in taxes. The private sector is the source of all wealth, and is what drives increases in the standard of living in a market-based economy. Taxes should consume as small a portion of national income as possible, and should not interfere with economic growth and investment.

8. Don't inhibit trade. In our increasingly global marketplace, the U.S. tax system must be competitive with those of other developed countries. Our tax system should not penalize or subsidize imports, exports, U.S. investment abroad or foreign investment in the U.S. Taxes on corporations, individuals, and goods and services should be competitive with other nations.

9. Ensure an open process. Tax legislation should be based on careful economic analysis and transparent legislative procedures. Tax legislation should be subject to open hearings with full opportunity to comment on legislation and regulatory proposals.

10. State and local taxes matter. The same general principles that apply to federal taxes also apply at the state and local level. Local, state and federal tax systems should be harmonized to the extent possible, including consistent definitions, procedures and rules.

We have some other goals too, but as many of these are manifestations of these principles, we'll unveil them as we go forward.

Labels: taxes

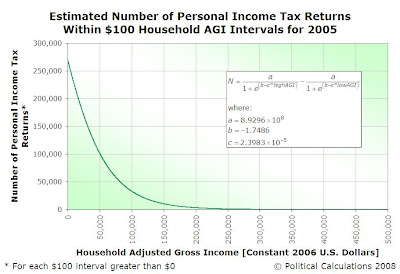

We've been tweaking our model of the distribution of household taxpayers in the U.S. and we've all but settled upon what we'll be presenting in this post and using in future discussions. First up, since we began building our distribution using the IRS' cumulative data for the number of tax returns filed by household Adjusted Gross Income (AGI), converted to 2006 U.S. dollars, we'll first present a chart showing our Zunzun-generated mathematical model along with our original data points:

Comparing the blue square points against the green curve, we can see right off that we have a fairly good match between our modeled data and the original data points. Believe it or not, the greatest errors between the actual data and our model occur at the low end of the income range. The magnitude of the error declines from 16.4% at an household AGI of $5,160 to 0.8% at an AGI of $20,639, with the average the errors for all values at or above this level coming in at 0.125%. The error visible at the household AGI of $206,398 is 1.7%, which is the greatest discrepancy between actual and modeled data for all values above $20,639.

As we'll discuss shortly, those larger errors at the lowest end of the income range of our model of U.S. taxpayer distribution won't present much of a problem in our little personal income tax project.

For our next chart, we used the mathematic model described above to determine the number of personal income tax filers for each $100 interval from $0 to $500,000. Actually, we did this for $100 intervals going well above $500,000, but we cut the chart off at this level because the number of returns filed declines very, very slowly from the already very low levels above it. This chart reveals where the bulk of U.S. personal income tax filers might be found according to their household Adjusted Gross Income:

The next two charts help reveal why the larger errors that exist between the actual data and our mathmatical model of the distributions of U.S. taxpayers in 2005 turn out to not be significant issue. In this next chart, we've multiplied the number of personal income tax returns within each $100 interval from $0 through $500,000 by the value of the midpoint of the indicated income interval. Doing so gives us a good approximation of the aggregate amount of household adjusted gross income that falls in that interval:

The peak in aggregate household Adjusted Gross Income of $5,084,754,013 occurs for the interval of $46,700 to $46,800. In other words, taxpaying households with an AGI between $46,700 and $46,800

The next chart applies the 2006 income tax rate schedule for Single taxfilers to this distribution of U.S. household taxpayer Adjusted Gross Income, which allows us to define the maximum potential income tax that could theoretically be collected for each $100 interval from $0 to $500,000, assuming no exemptions, deductions or other adjustments for income:

In this chart, we see that the combination of low incomes and low tax rates seriously reduce the amount of tax collections the federal government might obtain from low income earning households. And that's without reducing the amount of earned income that could be subject to personal income taxes by things like the standard deduction and personal exemptions or itemized deductions that reduce the amount of income subject to the personal income tax.

In fact, for 2006, with a standard deduction for Singles of $5,150 and a personal exemption of $3,300, at least $8,450 of adjusted gross income per income tax return would be fully exempt from personal income taxes. Add in married taxpayers filing jointly and/or dependents and/or itemized deductions and exemptions and the amount of adjusted gross income that's not subject to personal income taxes only gets bigger.

Big enough, in fact, that those large errors that we have between our model of the distribution of household taxpayer income and the actual figures at the low end of the income spectrum just kind of disappear (the beauty of multiplying by zero!) That means that our model of this very recent distribution of U.S. taxpaying households is something that we can use to, oh say, design a brand new, much simpler and effective tax code that provides the ability to find out how much you might pay as well as how much the federal government might collect.

Or maybe we ought to just make a tool that you can use to design your own tax code to find these things out for yourself!

We have a number of odds and ends to wrap up before we get there, but you can expect that tool in the very near future.

That tool is available now! Go build your own income tax!

Labels: income distribution, taxes

Welcome to the Friday, April 25, 2008 edition of On the Moneyed Midways, the only place where you'll find the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's blog carnivals dedicated to, well, business and money-related issues!

Welcome to the Friday, April 25, 2008 edition of On the Moneyed Midways, the only place where you'll find the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's blog carnivals dedicated to, well, business and money-related issues!

We're very much falling in between the editions of a number of the blog carnivals we regularly track. The weekly Odysseus Medal has been delayed while we're going to miss the Carnival of HR, the Carnival of Taxes, the Carnival of Trust, to name just three, until their next biweekly or monthly editions. In the good news department, the relatively new Money Hacks Carnival looks promising. We'll see if its hosts can sustain a good quality blog carnival in the weeks ahead.

And that's it for us this week! The best posts of the week that was await below....

| On the Moneyed Midways for April 25, 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carnival | Post | Blog | Comments |

| Carnival of Debt Reduction | The Power Of Visualization: Use Play Money to Track and Pay Off Your Debt | Your Finish Rich Plan | Sure, you could use the latest personal finance software and create all sorts of charts showing where your money goes, but will you really understand the impact of your money decisions and where it all goes until you break out the Monopoly money? |

| Carnival of Money Stories | Free Coin Counting At CoinStar Machines and Participating Banks | Money Blue Book | Wondering what to do with all those loose coins you've been accumulating? Raymond shows how a trip to your local grocery store's Coinstar machine can turn your change into an easier form of money to use. Better still, did you know that if you opt for the gift card option in changing your money, you can avoid Coinstar's money changing fee? |

| Carnival of Personal Finance | The Psychology of Money: “I Have to Have It”-The Impulse Purchase | Greener Pastures | Are you an impulse buyer? If you are, what can you do to control those shopping impulses? Lisa Spinelli considers the forces that motivate the impulse buy and what you can do to avoid a bad case of buyer's remorse. |

| Cavalcade of Risk | The Softening Market - How Far, How Fast? | Managed Care Matters | With the cost of food and gas going up so much recently, it might be understandable if you didn't know that the cost of insurance has been coming down. Joe Paduda says it's the first time that total premiums have dropped since 1943 in his business-oriented look at the state of the insurance industry in The Best Post of the Week, Anywhere! |

| Festival of Frugality | Grocery Shopping Series Part I: Cheaper Ground Beef | Out of Debt Again | Mrs. Accountability takes a lesson learned from her mother to show you how can save a lot on hamburger by taking a cut of meat on sale and having the grocery store butcher grind it instead of buying it pre-packaged. |

| Festival of Stocks | Missed Buying Philip Morris in the 1980s? You've Got Another Chance | A Slacker's Quest For His First Million | D weighs the pros and cons of buying shares of Philip Morris (NYSE: PM) and comes down in favor of picking up shares of the world's Number 2 tobacco company. |

| Money Hacks Carnival | All I Really Needed to Know About Managing Money I Learned From Music | Destroy Debt | Debbie Dragon lays down a 28 song soundtrack featuring classic hits that can teach people about money management! |

Previous Editions

- OMM's Running Index for 2008

- OMM's Running Index for 2007

- The Best Blogs Found in 2006 (and our full 2006 index)!

Labels: carnival

Government programs intended to help people often have a way of backfiring badly. The reason for this, of course, goes to the inherent knowledge problem that elected politicians and government bureaucrats have when shaping and executing public policy. In a nutshell, they just aren't capable of knowing enough to truly solve problems in a way that makes everyone better off and worse, in their arrogance that they can, the ignorance they do not acknowledge, or in the pursuit of a particular interest group's support, they often create new problems or exacerbate other ones in the process of "helping".

Government programs intended to help people often have a way of backfiring badly. The reason for this, of course, goes to the inherent knowledge problem that elected politicians and government bureaucrats have when shaping and executing public policy. In a nutshell, they just aren't capable of knowing enough to truly solve problems in a way that makes everyone better off and worse, in their arrogance that they can, the ignorance they do not acknowledge, or in the pursuit of a particular interest group's support, they often create new problems or exacerbate other ones in the process of "helping".

Harvard's Jeff Frankel recently cited an example of this phenomenon provided by his colleague Jeff Liebman, an expert on how the federal government's welfare assistance programs intended to help those in need instead effectively trap people into dependence (we've added the links and inserted paragraph breaks for improved readability):

Despite the EITC and child credit, the poverty trap is still very much a reality in the U.S.

A woman called me out of the blue last week and told me her self-sufficiency counselor had suggested she get in touch with me. She had moved from a $25,000 a year job to a $35,000 a year job, and suddenly she couldn’t make ends meet any more. I told her I didn’t know what I could do for her, but agreed to meet with her.

She showed me all her pay stubs etc. She really did come out behind by several hundred dollars a month.

She lost free health insurance and instead had to pay $230 a month for her employer-provided health insurance.

Her rent associated with her section 8 voucher went up by 30% of the income gain (which is the rule).

She lost the ($280 a month) subsidized child care voucher she had for after-school care for her child.

She lost around $1600 a year of the EITC.

She paid payroll tax on the additional income.

Finally, the new job was in Boston, and she lived in a suburb. So now she has $300 a month of additional gas and parking charges. She asked me if she should go back to earning $25,000.

I told her that she should first try to find a $35k job closer to home. Also, she apparently can’t fully reverse her decision to take the higher paying job because she can’t get the child care voucher back (the waiting list is several years long she thinks).

She is really stuck. She tried taking an additional weekend job, but the combination of losing 30 percent in increased rent and paying for someone to take care of her child meant it didn’t help much either.

We now see that between all the phaseouts of welfare benefits she had been receiving and the higher taxes that resulted from her taking on a job paying a higher income, which would incidentally place her roughly at the U.S.' 50th percentile for household income (scroll to the bottom of our post from yesterday for confirmation!), this mother faced exorbitantly high and punitive marginal tax rates in taking on a job that paid just $10,000 more than she made before. In fact, Liebman estimates she faces an effective marginal tax rate increase of 130% for having traded up to that $35,000 per year job.

And it was all done by government programs designed and intended to help people with low incomes! Government programs all designed, implemented and executed by elected politicians and government bureaucrats, who never considered that what they were doing could make the people they were trying to "help" so much more worse off. And because of their inherently limited knowledge and focus, negative outcomes like this situation are virtually guaranteed to occur.

It's a recurring problem that begs a solution - one that can overcome the overreaching belief of politicians and elected bureaucrats in their own competence and ability to effect positive change. Econlog's Arnold Kling has provided a bit of a starting point in considering how to effectively resolve the problem:

The problem is that when a poor person starts earning income, he or she loses eligibility to a variety of in-kind benefits, especially Medicaid.

In my view, the key to changing this is to change the default measurement of income from "only count cash income" to "include in-kind benefits as income." A cynic could say that those who prefer to ignore in-kind benefits do so in order to overstate poverty.

But the consequences are real. Because so many subsidies and benefits are phased out or cut off on the basis of cash income, the effective marginal tax rates on poor people are enormous.

The sensible approach is to include in-kind benefits as income. Then, in order to avoid an across-the-board cut in benefits, you would raise the cut-off and phase-out points be several thousand dollars, to allow for the effect of including in-kind benefits in income.

Arnold's argument that the full dollar value of public assistance welfare benefits that an individual receives should be taken into account when determining how much that person is effectively taxed is compelling. As elected politicians and government bureaucrats have consistently proven incapable of coordinating the assistance programs they implement, the taxes they demand and the real needs of the people trapped in an ineffective system, it's an issue that we'll be exploring in the very near future.

We figure that someone had better. Otherwise, all we'll get is more poorly considered policies sold under the banner of hope and change that can never deliver on an ultimately empty promise.

Want to see where Social Security's taxable income cap fits in with household income percentiles over time? We probably should have shown this chart with our post from yesterday discussing how to minimize risk in funding Social Security, but better late than never! The heavy black line in the chart below shows where Social Security's contribution and benefit base would fall, in constant inflation-adjusted 1982-84 U.S. dollars, from 1986 through 2005:

Note that the Social Security taxable income cap lags changes in household adjusted gross income by about a year, which is what you would expect since it's set after the National Average Wage Index is determined for the previous year!

And while we're at it, here's the same chart, but now with the household income data converted to be in constant, inflation-adjusted 2008 U.S. dollars:

Putting numbers to this chart for 2005, the equivalent value of the cap on income that can be taxed by Social Security is $97,742. That's up some 20.3% from 1986's inflation-adjusted level of $81,279! Meanwhile, for 2008, the value of Social Security's contribution and benefit base has been set at $102,000.

For reference, the floor defining the level of income needed to be part of the Top 50% of household incomes in the U.S. is $33,537 for 2005, up 0.2% from the figure of $33,483 for 1986, which underscores our main point of how stable incomes at lower levels are over time, which helps protect Social Security's ability to deliver its benefits at promised levels.

Labels: social security, taxes

When Social Security was launched, the amount of income subject to Social Security taxes was capped to ensure that the program would have a rock solid source of revenue to support the program's beneficiaries. Otherwise, the amount a Social Security recipient might receive each month could vary wildly from year-to-year, driven by volatility in the U.S. economy.

When Social Security was launched, the amount of income subject to Social Security taxes was capped to ensure that the program would have a rock solid source of revenue to support the program's beneficiaries. Otherwise, the amount a Social Security recipient might receive each month could vary wildly from year-to-year, driven by volatility in the U.S. economy.

Since the program was established as a pay-as-you-go system, with every dollar paid in via Social Security's payroll tax being paid out in the form of benefits to its recipients, securing a stable source of funding was essential to guaranteeing that those receiving benefits would receive the full amount of what they had been promised by the U.S. government.

The only way the program's originators could accomplish this task, as we discussed yesterday in asking why Social Security has a cap, was to set the maximum income that could be taxed to support the program well below the level at which volatility in the economy would drastically affect the amount of taxes on individual incomes collected in any given year.

In this post, we'll show you why that technique works, as well as why it may not be such a great idea to eliminate the cap on the amount of income upon which Social Security taxes may be imposed.

Top Income Earners Have the Most Volatile Income Over Time

Since we lack the breakdown of taxable income from the early days of the Social Security program, we'll instead look at the IRS data available for the years from 1986 through 2005.

We'll visualize this spreadsheet data to first show how the level of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) for households, adjusted for inflation (in constant 1982-84 U.S. dollars), has changed for households in the Top 50%, the Top 25%, the Top 10%, the Top 5% and the Top 1% over this period:

Right off, we see that the inflation-adjusted incomes of U.S. households is the most volatile for those at the top of the income-earning spectrum, while it is the most stable for those at the low end. For instance, if we look at the years coinciding with the peak of the Dot-Com stock market bubble in 2000 through its burst and the following recession in 2002, we see that the incomes of the Top 1% of all income-earning households plummeted some 12.8% from its peak in 2000. We also see that the incomes of the U.S.' top income earners stayed depressed through 2003 and 2004, before recovering to the levels of 2000 in 2005.

Meanwhile, we see that the drop-offs for these years at lower levels of income are much less drastic. Running the numbers, we find that between 2000 to 2002, the adjusted gross incomes at the level defining the threshold of those in the Top 5% declined 5.6%, while the income threshold for the Top 10% fell some 3.7%, the Top 25% threshold dropped 2.2% and the Top 50% dipped just 0.9%.

Clearly, the volatility in income generated from year to year is most volatile for those at the top. Simultaneously, we confirm that the incomes of those at the low end are the most stable over time.

Volatility Levels Across All Incomes

Our next chart stacks these adjusted gross incomes on top of one another, which allows us to see what the overall impact of this top-end volatility would be to the Social Security program:

Taken together, we see that the total level of adjusted gross income plunged by some 8.9% between 2000 and 2002, marking the largest, sharpest drop in the years for which we have data.

What Would This Mean for Social Security?

If there were no cap upon the amount of income that could be taxed to support Social Security today, the amount of taxes on income collected to support the program would have dropped by this 8.9% figure between 2000 and 2002. That, in turn, would affect the program's long term ability to pay benefits in the future.

Right now, as a result of reforms undertaken in the 1980s to prepare for the large scale retirement of the Baby Boom generation, Social Security takes in far more money than it pays out in the form of benefits. The excess funds taken in through the Social Security program's payroll income taxes is directed to its trust fund.

However, in less than ten years, as the Baby Boomers retire in large numbers, Social Security's trust fund will begin running annual deficits, as the amount Social Security must pay out in benefits will exceed the amount it takes in through payroll income taxes.

Worse, once Social Security's trust fund is depleted and it reverts fully back to a "pay-as-you-go" program in 2041 (as currently projected by the program's professional actuaries), that kind of drop in funding for the program would fully translate into a major cut in the benefits paid out to all Social Security recipients.

Note: That kind of cut in benefits paid out would be on top of the 26% reduction in benefits that will occur when the Social Security trust fund is fully depleted, even if no recession or other economic event occurs between now and then that would drastically reduces the payroll tax collections that support the program!

We'll note that there are studies that suggest that eliminating the Social Security taxable income cap would extend the amount of time that Social Security's trust fund be able to operate without deficits by seven years. That would delay the date of reckoning for Social Security recipients by a similar amount of time.

Projecting ahead, we figure that anyone born after 1960 could very reasonably expect to be affected by such recession-period benefit cuts, on top of the large cuts in benefits stemming from the depletion of Social Security's trust fund by the baby boomers, as a direct consequence of the greater level of volatility in payroll tax collections that would result from eliminating Social Security's income cap.

By contrast, since the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes at present falls roughly in line with today's Top 10% income threshold, capping the amount of income that could be taxed at this level would result in a 2.6% cut in benefits paid out to Social Security recipients during trying economic times.

And if the maximum amount of income subject to Social Security taxes were reduced to be back in line with the level of income setting the threshold for the Top 25% of household incomes, just a bit ahead of where this level was set back in 1986, the size of the cut in Social Security benefits in a similar period of recession would be just 1.8%.

We therefore find that the cap on the amount of income that can be taxed to support Social Security protects the ability of the program to provide benefits at the level it promises, especially in recessionary periods.

Now, let's make this personal. If you plan to rely on Social Security benefits to support your household in whole or in part in your retirement years, how big of a cut in your benefits could you afford to take if the U.S. economy turned sour for several years?

Why increase your risk in retirement?

Previously on Political Calculations

- Why Does Social Security Have a Cap? - the first part to this second part!

- Approximating Social Security's Rate of Return - our tool for finding what rate of return you can expect to realize from your "investment" in Social Security.

- Slashing Social Security Benefits - How much of your "promised" benefits will be left when the Social Security trust fund runs out of money? Our tool provides the answers you need to plan now.

Update 23 April 2008: We made minor corrections the chart showing the household adjusted gross income floors from 1986 through 2005. No, the income floors shown shouldn't have been in "billions" of 1982-84 chained U.S. dollars!

Labels: social security, taxes

As of 2008, payroll taxes on income to fund Social Security in the U.S. are limited to the first $102,000 of an individual's annual taxable earnings. According to the Social Security Administration, that's up $4,500 from the limit of $97,500 just the year before and up a total of $60,000 since 1986, just 22 years ago.

As of 2008, payroll taxes on income to fund Social Security in the U.S. are limited to the first $102,000 of an individual's annual taxable earnings. According to the Social Security Administration, that's up $4,500 from the limit of $97,500 just the year before and up a total of $60,000 since 1986, just 22 years ago.

With that big of a dollar increase over such a relatively short period of time, a good question to ask is "why does Social Security even have a cap on the amount of an individual's income that can be taxed?" After all, the cap on the amount of an individual's income that can be subjected to Social Security taxes has existed from the very beginning of the program.

It's often cited that the U.S. Social Security program's originators intended set the maximum taxable wage base to limit the amount of benefits that those earning more than this amount might receive. The Heritage Foundation's Rea S.Hederman, Jr, Tracy L. Foertsch and Kirk A. Johnson make this point in looking at the potential negative impact upon removing the income cap back in 2005 (emphasis ours):

It's often cited that the U.S. Social Security program's originators intended set the maximum taxable wage base to limit the amount of benefits that those earning more than this amount might receive. The Heritage Foundation's Rea S.Hederman, Jr, Tracy L. Foertsch and Kirk A. Johnson make this point in looking at the potential negative impact upon removing the income cap back in 2005 (emphasis ours):

Social Security was created as a pay-related retirement system, not as a welfare program that redistributes money from workers to those in need regardless of whether or not its recipients had paid into the system. The benefits that retirees received were linked to the taxes that they had paid when in the workforce. Social Security was intended to supplement rather than replace private sources of retirement income by providing only a basic, government-guaranteed source of income.

Maximum Level of Benefits and Maximum Taxable Wages. Within this context, Congress determined that it was appropriate to set an upper limit on the amount of income that Americans could receive from the Social Security program. A limit on benefits, combined with the principle that workers' benefits should relate to the amount of money that they paid into the system, made an upper limit on the taxes that workers would pay appropriate.

However, this explanation of why the Social Security tax cap exists falls short in our view. As amended in 1939 prior to making its first monthly payments, the program would pay out in benefits each year the amount that the program had collected through dedicated payroll taxes each year in a "pay-as-you-go" system. Why bother limiting the payouts for those who had paid the most? Why limit the taxes paid to support the Social Security program?

We find that the real answer perhaps lies in the economic environment of the Great Depression and the experience the government had obtained in collecting income taxes, after the 16th amendment to the U.S. Constitution permitted the federal government to impose them.

After taking effect in 1913, the federal income tax soon proved to be a highly effective means of providing funding for the U.S. federal government. In fact, the new income tax was so successful that it more than compensated for the tax collections lost when the government enacted the 18th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, which prohibited the sale of alcohol in the United States, which took effect in 1920.

So successful, in fact, that the new national income tax may have enabled the ability of the government to enact Prohibition in the U.S., as Don Boudreaux has argued:

Prior to the creation in 1913 of the national income tax, about a third of Uncle Sam's annual revenue came from liquor taxes. (The bulk of Uncle Sam's revenues came from customs duties.) Not so after 1913. Especially after the income tax surprised politicians during World War I with its incredible ability to rake in tax revenue, the importance of liquor taxation fell precipitously.

By 1920, the income tax supplied two-thirds of Uncle Sam's revenues and nine times more revenue than was then supplied by liquor taxes and customs duties combined. In research that I did with University of Michigan law professor Adam Pritchard, we found that bulging income-tax revenues made it possible for Congress finally to give in to the decades-old movement for alcohol prohibition.

Before the income tax, Congress effectively ignored such calls because to prohibit alcohol sales then would have hit Congress hard in the place it guards most zealously: its purse. But once a new and much more intoxicating source of revenue was discovered, the cost to politicians of pandering to the puritans and other anti-liquor lobbies dramatically fell.

But that boom in revenues all came before the years of the Great Depression. Don Boudreaux describes the environment that motivated the repeal of Prohibition:

Despite pleas throughout the 1920s by journalist H.L. Mencken and a tiny handful of other sensible people to end Prohibition, Congress gave no hint that it would repeal this folly. Prohibition appeared to be here to stay -- until income-tax revenues nose-dived in the early 1930s.

From 1930 to 1931, income-tax revenues fell by 15 percent.

In 1932 they fell another 37 percent; 1932 income-tax revenues were 46 percent lower than just two years earlier. And by 1933 they were fully 60 percent lower than in 1930.

With no end of the Depression in sight, Washington got anxious for a substitute source of revenue.

That source was liquor sales.

While the federal government turned to taxing liquor sales once more to support its basic operations, the originators of Social Security could not help but be aware of the issue of funding the program, upon which recipients would become partially dependent in supporting themselves, using a new tax on individual incomes. How would they escape the volatility inherent in income tax collections from year to year?

The only way to guarantee that the Social Security program would be able to meet its promised obligations to its beneficiaries would be to remove the element of extreme volatility from its income tax dependent revenue source. And the only way to do that would be to set a statutory limit on the amount of income that could be taxed, and set that limit well below the income levels that were the most volatile from year to year: those of the highest income earners.

The only way to guarantee that the Social Security program would be able to meet its promised obligations to its beneficiaries would be to remove the element of extreme volatility from its income tax dependent revenue source. And the only way to do that would be to set a statutory limit on the amount of income that could be taxed, and set that limit well below the income levels that were the most volatile from year to year: those of the highest income earners.

With this cap on the amount of income that could be taxed in place and the amount of benefits that it would pay out linked to it, Social Security would be capable of weathering the extreme storms in the U.S. economy and ensure that beneficiaries would always receive the level of benefits they had been promised.

That's why Social Security limits the amount of income that can be taxed to support the program. Tomorrow, we'll show you why that cap still makes sense today.

Labels: social security, taxes

Welcome to the Friday, April 18, 2008 edition of On the Moneyed Midways, where we've identified the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's blog carnivals dedicated to business and money-related issues.

Welcome to the Friday, April 18, 2008 edition of On the Moneyed Midways, where we've identified the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's blog carnivals dedicated to business and money-related issues.

After last week's edition, we were ready for trouble this week, but fortunately, all was quiet and no pseudo or parody haiku was to be found in any of the carnivals we've featured this week!

So let's get right to it then! The best posts of the week that was await you below....

| On the Moneyed Midways for April 18, 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carnival | Post | Blog | Comments |

| Carnival of Debt Reduction | An Illustration of Why Saving Money is Harder than Spending Money | Broke Grad Student | The Broke Grad Student employs highly sophisticated graphic artist skills to show with crystal clarity why building savings is harder than taking on debt! |

| Carnival of HR | Watching China's Rise | Talent in China | Frank Mulligan looks at China's rampaging job market, where the country's export driven growth powers average annual salary growth of 16% and average job tenures of 18 months, which makes finding and keeping talent a difficult task. |

| Carnival of Money Stories | Rogue Debt Collectors Illegally Freeze Debtors' Accounts | Your Finish Rich Plan | Horror stories of people cut off from their bank accounts as a result of aggressive, and as it turns out, illegal conduct of overly aggressive debt collection agents. Absolutely essential reading for outlining what income debt collectors cannot touch by law. |

| Carnival of Personal Finance | Outsource to Your Kids Already! | My Family's Money | Steward suggests turning to the child labor market within your household to take on those mundane tasks when you'd rather be lazy, listing the benefits for both you and your children! |

| Carnival of Real Estate | Your Money or Your Life | Larry's Take on the Cocoa Beach Florida Real Estate Market | Larry Walker reflects on the choices that buyers often make when selecting their next home and finds that they're often choosing between their money and their lives. The Best Post of the Week, Anywhere! |

| Festival of Frugality | The Hour: How 60 Minutes a Week Can Save Hundreds of Dollars on Food | Cheap Healthy Good | Kris shows how just an hour a week of taking a quick inventory, scanning for deals, a little coupon clipping and making a plan can save a lot of money in household food costs. Absolutely essential reading, because when you think about it, what you save by taking an hour like this might be more than you would make in an hour at a "real" job. |

| Festival of Frugality | How to Make 10 Ordinary Things Last Longer | The Digerati Life | We've been following the Silicon Valley Blogger's planned transition from a two income household to just one, so we have pretty good confidence that any and all of SVB's ten suggestions for stretching the life of various household products will work as advertised! |

| Odysseus Medal | I Want to Be a Lister - The Listing Presentation - The Objections | BloodhoundBlog | The Black Pearl in a week without an official Odysseus Medal winner, Phoenix-area real estate institution Russell Shaw looks at the objections that buyers might have for listing their home with a realtor and offers agents a thorough list of questions to answer in crafting an effective listing presentation. |

Previous Editions

- OMM's Running Index for 2008

- OMM's Running Index for 2007

- The Best Blogs Found in 2006 (and our full 2006 index)!

Labels: carnival

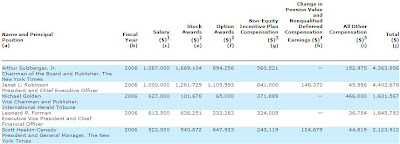

In recently reviewing the New York Times' SEC filings to chart its declining circulation, we found something a bit surprising and, in our view, potentially misleading for the company's common stock shareholders. First, here's the table showing the NYT's summary of executive compensation that the company provided in their 2008 proxy statement (page 40):

Now, here's the summary compensation table published in the New York Times annual meeting notice and proxy statement from one year ago (page 35):

So we see that in comparing the two tables, the "Bonus" column has disappeared. Let's look next at the Summary of Executive Compensation table from the New York Times' 2006 proxy statement (page 22):

Hey look, huge bonuses! But wait a minute - isn't that $560,521 figure for Arthur Sulzberger Jr.'s Fiscal Year 2005 bonus exactly the same one we saw listed for him in the 2007 proxy statement's table as "Non-Equity Incentive Plan Compensation" for Fiscal Year 2006?

Why, yes it is! And it appears that Mr. Sulzberger asked that his 2006 bonus "be limited to the same amount he was paid a year earlier," which accounts for why the numbers are the same.

Only thing is, it's now called "Non-Equity Incentive Plan Compensation," instead of "bonus."

And that new column in the 2008 proxy statement for "Bonus," which suggests that Mr. Sulzberger isn't receiving a bonus for Fiscal Year 2007, is now looking really misleading. He is, and it's a lot of money, but now it's being called something else.

But with that "Bonus" column back in the table, how long might it be before it's filled again?

If you were a shareholder going to attend the company's annual meeting on Tuesday, April 22, 2008, knowing that large layoffs are coming, that advertising revenues are off substantially in the face of sharply declining circulation, and now this shift in terminology used in the company's proxy statement to muddy the waters, as it were, regarding its executive compensation, don't you think you should be getting some answers as to how they might expect to realize these bonuses? Does the company's leadership have any real plan at all to turn the newspaper's declining fortunes around? Or are they just there to collect paychecks and stock dividends for as long as the business lasts?

It's not like the journalists at the New York Times' business section will ask tough questions of their bosses for you! Not if CNBC's interview of GE CEO Jeffrey Immelt is any indication of how media employees interview their bosses....

Update 18 April 2008: Did we mention the New York Times' declining fortunes? The Times' just announced an unexpected and large first quarter loss for 2008.

Labels: business, stock market

The Bureau of Labor Statistics released the Consumer Price Index for March 2008 today, which means that we can finally update our signature tool for finding the average performance of the stock market between any two calendar months since January 1871, The S&P 500 at Your Fingertips!

But wait, that's not all! With the first quarter of 2008 now officially over, and the fourth quarter of 2007's earnings finally finalized, we've gone back and revised all our dividends and earnings data in the tool going back as far October 2007. Quick summary of the revisions: dividends same to better, earnings worse.

Meanwhile, as the March 2008 inflation figure (CPI-U) came in at 213.528, a 4.0% increase over March 2007, investments in the S&P 500 held over this time have fared worse that just the point drop in the index value since December 2007 would suggest.

Of course, we just don't talk about the market. We take pictures of it as well! First up, here's he S&P 500's average monthly index value since January 1952, which covers the modern era of the U.S. stock market:

Next, here's the S&P 500's trailing year dividends per share from January 1952 through March 2008:

And here's an update of our signature chart showing the S&P 500's average monthly index value against its trailing year dividends per share since June 2003, coinciding with the most recent period of market stability and the beginning of a disruptive event in the market in January 2008, complete with a bonus point showing where the stock market is as of the April 15, 2008 market close:

Finally, here's an update of our chart tracking the Price Dividend Growth Ratio, or rather, the ratio between the year-over-year growth rate of stock prices and the year-over-year growth rate of dividends per share, from January 1952 to March 2008:

These latter two charts indicate that the turmoil being created by the troubles of the housing sector and financial institutions are, as of March 2008, largely contained to those sectors. The stock market is so far proving to be somewhat resilient and the level of distress in the market is not yet building toward a spike.

That's important as spikes in stock market distress often coincide with recessions in the U.S. economy. For that to happen, a serious erosion of earnings would need to occur that would then lead to zero year-over-year growth in the market's dividends per share. The trend at present is that this rate of growth is declining, but still well in positive growth territory (as projected by S&P, the year-over-year dividends per share growth rate will slowly decreased from 10.45% in December 2007 to 9.27% by year end.)

However, a spike in stock market distress is not a requirement for a recession to occur, as the U.S. economy is a lot bigger than its stock markets. At present, the best analog we have in our historical data to today's economy and market conditions is the period from 1978 to 1980.

Ultimately, we may see things play out along those lines, albeit on a much smaller scale, as both inflation and unemployment are much lower today than in those strained days. With the Price-Dividend Growth Ratio at -0.58 as of March 2008, we note that a negative value of this ratio often precedes periods of real distress in the stock market.

Labels: SP 500, stock market, update

Why does the U.S. government hate people earning between $30,650 and $45,115 so much?

Why does the U.S. government hate people earning between $30,650 and $45,115 so much?

We asked this question yesterday when we took a closer look at the changes in tax rates between 1954 and 2006, finding that the people represented by this income range saw just a 4% reduction in their marginal tax rates, while virtually all income earners saw at least double-digit tax rate percentage reductions. These other percentage reductions in marginal tax rates from 1954 to 2006 ranged from 17% to 50% over the adjusted gross income spectrum covering $0 through $100,000 for households in inflation-adjusted, constant 2006 U.S. dollars.

As we'll show you next, and as our post title states, the reason the people and households who fall within this income range have never had their tax rates lowered very much in the U.S. is because they earn more income than any other group in the U.S. Those individual and household personal income tax filers within this $30-$45,000 range also provide the most stable source of tax collections for the U.S. government from personal income taxes, upon which the U.S. government relies to fund its massive levels of spending.

Our first step in answering the question was to find the distribution of income for income tax filers. The most recent figures we could obtain were from 2005, and the key assumption in our analysis is that the distribution of income within the households represented in the IRS' statistics of income did not change significantly from 2005 to 2006.

We took the 2005 data for the accumulated size of adjusted gross income for tax returns filed by all households for that year, adjusted the various adjusted gross income levels to be in constant 2006 dollars.

From there, we took the inflation-adjusted adjusted gross income data and the accumulative number of tax returns filed in 2005 and used ZunZun's 2-D function finder to fit a curve to the data.

We selected the second-ranked option provided by ZunZun's results, as it represented an ideal combination of low error and a minimal number of factors, which was given by the NIST MGH09 distribution:

Approx. Number of Returns = a * (x2 + b*x) / (x2 + c*x + d)

where "x" is given by adjusted gross income.

To get the distribution of income, we next used this equation and the fitted coefficients given by ZunZun to find the approximate number of returns for each $100 adjusted gross income interval between $0 and $100,000. This number is given by the difference between the values obtained by solving our distribution equation at the high end of the income interval and the low end. The results are provided in the chart below:

We next approximated the accumulated adjusted gross income earned for each $100 interval represented by this distribution of personal income tax returns (for both individuals and households). We did this using a quick-and-dirty technique that involves simply multiplying the mid-range of the $100 interval by the approximate number of returns filed given for the interval by the distribution. The following chart shows our results:

The aggregate amount of Adjusted Gross Income (AGI) in the chart above is provided in 2006 U.S. dollars.

And so, we confirm using our back-of-the-envelope analysis that those individuals and households filing personal income tax returns in the income range of $30,650 to $45,115 do, in fact, earn the highest amount of income, which accounts for why these people have never had their marginal tax rates significantly lowered.

We believe this inflation-adjusted income range represents something of a sweet spot for personal income tax collections for the U.S. government, as those with lower incomes can be expected to move up into this range in good years, while those with higher incomes might be expected to move down into this range in bad economic years.

As a result, the U.S. government seeks to capitalize on the stability provided by those individuals and households within the $30-$45,000 income range and maximize its personal income tax collections by sustaining the highest marginal tax rates possible.

And that's why the government hates people earning between $30,650 and $45,000 (in constant 2006 U.S. dollars), as demonstrated by its unwillingness to provide those falling within this income range with significant tax rate cuts.

Have a happy Tax Day!

Labels: taxes

We decided to take a closer look at our chart comparing the steeply progressive income tax rates of 1954 against the much flatter income tax rates of 2006, and in doing so, came up with a question: Why does the government not want to give big tax breaks to people who make between $30,650 and $45,113 (in constant 2006 U.S. dollars)?

To understand why we're asking, here's our original chart with the region highlighted (and yet another slightly different version of our question):

And here's a close up view of that area of interest, which also shows the percentage by which the various tax rates have been slashed over the years from 1954 to 2006

Previously, in another project, we noted that the 95th percentile for individual income earners was $97,656 in 2005, which means that our chart above applies for a very large percentage of income tax payers in the U.S. Given that those making less than this amount and more than this amount have realized the greatest percentage decreases in their marginal tax rates, why is it that the government won't cut the people in the $30-45,000 income range that much of a break?

We'll attempt to answer ourselves tomorrow!

Labels: taxes

Welcome to the Friday, April 11, 2008 of On the Moneyed Midways, where we bring your the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's business and money-related blog carnivals!

Welcome to the Friday, April 11, 2008 of On the Moneyed Midways, where we bring your the best business and money-related blog posts from the best of the past week's business and money-related blog carnivals!

Luke, of Real World Really, committed one of the cardinal sins of hosting a blog carnival this past week. What could be so bad you ask? In one word: Haiku.

To understand why, let's return to our rant on the subject from the May 26, 2006 edition of OMM, in which we had the following to say:

We begin this week's edition of Political Calculations' weekly wrapup of all the major business, capitalist, debt-reducing, investing, marketing, personal finance and frugal-living blog carnivals, On the Moneyed Midways with a rant on how *not* to present the posts submitted in a blog carnival.

We can summarize our position in one word: Haiku. While we greatly appreciate the creativity needed to master this exquisite form of Japanese poetry, it should not, ever, be used to describe the posts that have been contributed for a blog carnival. Not ever. Never. Ever. And in case we haven't made our point clear, you may discover the many reasons why for yourself by scrolling down and visiting the Carnival of Debt Reduction for this week....

Unfortunately, we don't have to change our suggestion for discovering why Haiku is such a bad choice around which to organize a blog carnival, as this week's Carnival of Debt Reduction is once again the victim of haiku-contamination. Even worse, since we now have a repeat offender, we have to lay down the law. We will no longer feature any edition of a blog carnival that features verses of haiku, which we find to be utterly incapable of adequately communicating why we should consider clicking through on a link to a contributed post.

It wastes our time and it wastes the carnival contributors' efforts. Stop the carnage now, blog carnival hosts, don't ever do it! Not ever. Never. Ever.

Update: It's also, as f/k/a editor David Giacalone, points out, not real haiku. For anyone who wants to know the difference between the good stuff and what we're railing against, see "Is it or ain't it haiku?"

Other than that, the rest of this week's blog carnivals were fine, Mrs. Lincoln. Really! Aside from the haiku disaster, this past week is one of the best of the year so far. Just keep scrolling down for the best of the week that was....

| On the Moneyed Midways for April 11, 2008 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Carnival | Post | Blog | Comments |

| Carnival of Debt Reduction | Earning More Doesn't Help If You Don't Spend Less | I've Paid Twice for This Already… | Paidtwice shares a lesson learned the hard way that you can't control your debts until you control your spending. |

| Carnival of Money Stories | Have You ever Had to Tell the Boss "No?" | Free Money Finance | FMF links to a WSJ story about a lawyer who had to make a quick decision to choose between work and home, using it to launch a discussion of when others have been compelled to make the choice for themselves. |

| Carnival of Personal Finance | The Annual Cost of Pet Ownership: Can You Afford a Furry Friend | Money Under 30 | David's friend Dan adopted a couple of kittens after buying a condo, and was surprised at how much it costs to own cats. Absolutely essential reading for putting the one-time and ongoing expenses of owning a pet up front for consideration! |

| Carnival of Real Estate | The 24 Worst Bad MLS Photos of the Year | Reagent in CT | Is your real estate agent really working for you or against you when they take pictures of your house to put on the MLS? Athol has a don't miss listing of the worst photos uploaded to the MLS to "help" make the sale! |

| Carnival of Taxes | A Fistful of Dollars: the CEO Tax Dodge | SOX First | Some big company CEOs get some pretty amazing perks, but Leon Gettler is amazed that several corporate titans have deals that requires their companies pay for the income taxes that come with their use and abuse of these perks. |

| Carnival of Trust | The 10 Changes a CEO Needs to Make to Win Young Consumers - #10 Focus on Trust not Technology | mobileYouth | The Best Post of the Week, Anywhere! Graham Brown explains the value of trust in forging strong relationships with young consumers and established businesses, and identifies why brands such as Starbucks has credibility where others like The Gap does not. |

| Carnival of Trust | Carnival of Trust | True Colors Consulting | If you're a blog carnival host looking for an outstanding example of how to create a compelling blog carnival, look no further than this week's Carnival of Trust. Not one lick of haiku anywhere in The Best Carnival of the Week, Anywhere! |

| Cavalcade of Risk | The Bear Stearns Fallout and a Solution | SOX First | Leon Gettler compares the Fed's recent actions to "bail out" the U.S. banking indisutry with actions taken in both Japan and Korea following banking crises in those countries and comes down solidly in favor of the Korean solution in Absolutely essential reading! |

| Economics and Social Policy | The Difference Between Legal Tax Avoidance and Illegal Tax Evasion | Money Blue Book | Raymond describes the difference between tax avoidance (which is legal) and tax evasion (which is not), in perhaps the most timely post of the week before April 15th in the U.S.! |

| Festival of Frugality | How to Haggle and Pay a Lower Price | Finance Blog | Sometimes, it's as easy as asking, but the Finance Blog goes the extra mile to help you get the lowest price or a better value through the art of negotiation. |

| Festival of Frugality | Find IT on eBay | Pants in a Can | Pants in a Can used to buy his favorite jeans at The Gap, but they discontinued the style. Fortunately, he discovered that he could still get the jeans via eBay, brand new, and at an 85% discount! |

| Festival of Stocks | Why You Should Be a Lazy Trader | Trading Trainer | A.J. Brown provides an invaluable lesson in why it pays to "wait for the right set-ups before putting your hard-earned money into the market" as part of your trading discipline. |

| Odysseus Medal | What Do I Do Now? | BloodhoundBlog | Highly successful Phoenix-area Realtor Russell Shaw counsels a veteran agent, a new agent, and by extension all real estate agents, on how to shape their careers and overcome the problems and challenges they face. Absolutely essential reading! |

Previous Editions

- OMM's Running Index for 2008

- OMM's Running Index for 2007

- The Best Blogs Found in 2006 (and our full 2006 index)!

Labels: carnival

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.