Order may be said to exist in the stock market whenever stock prices are closely coupled with their underlying dividends per share and begin following a stable trajectory over time. When that kind of order exists, stock prices become very predictable because the variation in stock prices with respect to that overall trajectory may be described by a normal statistical distribution.

Although it's taken several months to get enough data to make the call, the stock market began behaving in a very orderly fashion in February 2011. Here's the visual proof that order may have finally returned to the stock market:

What we see is that after an extended period of disorder that began in January 2008, it appears that order resumed in the stock market three years later, either in January or February 2011.

Even more remarkably, the new period of order appears to be following the same trajectory that defined the previous period of order that existed between June 2003 and December 2007.

How long that condition might last remains to be seen. If the pattern we currently observe holds, and we'll need several more months of data to make that determination, we will be able to use our normal method for forecasting future stock prices.

But is what we're seeing the result of a spontaneous, or natural, emergence of order in the market? Or is it the result of a managed condition, such as the Fed's targeting of stock prices in managing their quantitative easing program, which we speculated might happen in February 2011?

We'll have to take on that question soon....

Labels: chaos, SP 500, stock market

Assuming you'll live to what the federal government considers to be "full retirement age", you have reasonably good odds of living to Age 84.

The only problem though is that for many of these Americans, the trust funds that support the government benefits upon which they will rely during their retirement years will run out of money during their lifetimes. When that happens, the amount of cash paid out to support these benefit programs will be slashed, as promised by current law.

The benefits in question are those covered by the Social Security Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which provides steady income to retired Americans, the Social Security Disability Insurance Trust Fund, which provides cash for Americans who have disabilities, and Medicare's Hospital Insurance Trust Fund, which covers the cost of hospitalization for retired Americans.

So who will be the Americans most likely to be negatively affected by these trust funds being depleted during their lifetimes?

To find out, we started with the years that Social Security's Trustees estimate that each of these trust funds will no longer have enough money to pay out to Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries, and worked backwards to identify the birth years for people who will be between the ages of 67 and 84 when that happens, which we identified on our chart below:

Here, a majority of people born before the birth year indicated on the left of the blue bar for each trust fund can live to Age 84 without seeing their Social Security or Medicare benefits decreased during their lifetimes.

Meanwhile, people born after the birth year indicated on the right of the blue bar won't necessarily have to worry as much about their Social Security and Medicare benefits being cut, because they'll never receive the generous amount of benefits that individuals born in earlier years received during their lifetimes.

But the blue bar itself indicates the real danger years for Social Security and Medicare beneficiaries. People born between these years will very likely start receiving the really generous benefits supported by the Social Security and Medicare trust funds, but will see those benefits dramatically decline during the part of their lives during which they will rely upon them most.

Just as today's politicians have promised!

Labels: demographics, health care, social security

What is the hidden cost that Americans are paying to have the U.S. federal government spend so much money?

To answer that question, let's take a closer look at when U.S. federal government spending really went out of control. Here, if we track the U.S. federal government's spending [1] per U.S. household against median household income since 1967 [2], we see that federal spending discipline really broke down after 2007, rising considerably in 2008 with the beginning of the major bank bailouts of that year, but really skyrocketing in 2009 as the U.S. recession really took hold with the collapse of much of the U.S. automotive industry in late 2008 and early 2009.

Since then, the amount of federal government spending per U.S. household has continued at extremely elevated levels, as the U.S. has continued to set new records for the U.S. government's annual budget deficit in both 2010 and 2011.

Americans are paying a tremendous hidden cost for racking up so much debt so quickly. To uncover the amount of that hidden cost, we'll need to consider how the people lending money to the U.S. government are coping with the risk of the U.S. potentially defaulting on the interest payments it owes the people, institutions and governments who have lent it money.

They are coping with that potential risk in two ways: they're requiring the U.S. government to pay higher interest rates than it would otherwise have to if the amount of debt the government has taken on were not so large and they're buying insurance that will pay them back in full should the U.S. government actually default on its debt payments.

It is the changing cost of that insurance since the current national debt crisis began that provides the key for being able to work out the hidden cost of America's excessive national debt problem.

The insurance policy that lenders take out against the possibility of a borrower going into default is called a Credit Default Swap, or CDS, where the cost of the policy is directly related to the estimated probability that the borrower will default within a certain period of time.

Before 2008, it was considered by bond investors to be highly unlikely that the United States would ever default on its national debt. And even today, it's still highly unlikely. However, that doesn't mean that the potential risk of a default hasn't increased. Tapping Bloomberg's historic data for the value of the CDS for U.S. Treasuries, we see that the CDS spread for U.S. Treasuries has increased from roughly 7.0-9.0 some three years ago, at a very early point in the U.S. national debt bubble, to spike at 100 at the peak of the crisis, before falling back to today's levels of 47.0-50.0.

What we see is that a roughly 40 point increase in the cost of insuring the U.S. national debt through Credit Default Swaps from the effectively default-risk free period before 2008 to today's not default-risk free levels would appear to have become a permanent, ongoing feature. Especially as major credit rating agencies are acting to downgrade the debt outlook for the U.S from stable to negative, signaling that unless the U.S. debt trajectory changes in the next two years, they may have to begin lowering the U.S.' current AAA credit rating to confirm the increase in risk to lenders.

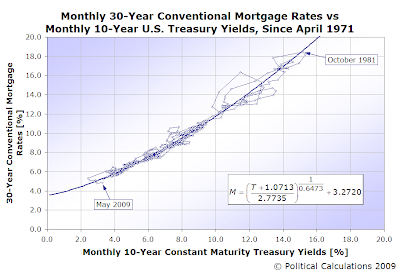

But that doesn't mean that government bond investors aren't already making the U.S. government pay higher interest rates today! We can use the relationship we found between the yields for 10-year government bonds and their CDS spread to estimate how much higher interest rates are today than they would otherwise be if the risk of default were effectively non-existent as it was before 2008.

Here, we found that if a country sees its CDS spread rise by 90-110 points, which likely corresponds to an increase the probability that it will default on its debt, we should see the interest rates on the 10-year bonds it issues go up by roughly 1%, as investors seek to secure greater returns before such a default might take place.

At a sustained 40 point increase above the default-free risk level, we would estimate that the interest rate that investors require the U.S. government to pay on its 10-Year Treasury Bond is about 0.4% higher than it would otherwise be. Today's yields on a 10-Year Treasury of 3.15% would instead be about 2.75%, if not for the increased risk of default.

That effective increase in the yield on U.S. Treasuries in turn has real economic consequences. In April 2011, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston estimated that a 1% decrease in the 10-Year U.S. Treasury yield would increase U.S. GDP by 2.65%, as this benchmark rate effectively sets the base for many interest rates in the U.S. economy, such as for mortgages or any other borrowing activity, which get cheaper when the yield of the 10-Year U.S. Treasury falls.

This multiplier effect also works in reverse. A 1% increase in the 10-Year Treasury yield would act decrease U.S. GDP by 2.65%.

In the case of when the effective yield of a 10-Year U.S. Treasury is increased by 0.4%, as we've estimated, the effect will be to decrease U.S. GDP by roughly 1.0%.

This phenomenon might go a long way toward explaining why the U.S. economic recovery following this latest recession has been so sluggish compared to previous recessions. Extremely elevated national debt levels driven by the U.S. federal government's excessive level of spending and the small increase in the risk of default they portend might be robbing the federal government's series of economic stimulus measures of effectiveness and could very well be holding the U.S. economy back from making a more robust recovery.

At the end of the fourth quarter of 2010, U.S. GDP stood at $14.9 trillion. If U.S. GDP has been decreased by 1.0% of that figure, we find that the hidden cost of having the U.S. national debt skyrocket in recent years to be roughly $1.5 trillion. Just in 2010 alone.

That figure coincidentally happens to be the projected deficit for the U.S. government in 2011, so Americans can continue to expect that the shackles of the national debt will continue to hold them down.

Notes

[1] The data for U.S. government spending is taken from the White House Office of Management and Budget's historical tables for the Budget of the U.S. Government for Fiscal Year 2011.

[2] 1967 is the year in which the U.S. Census first began reporting median household income for the United States, which it has done annually since. The data, most recently updated through 2009, is available in this spreadsheet. This data source also indicates the number of U.S. households, which we used to calculate the total amount of federal government outlays per U.S. household.

Image Credit: The Pantheon.

Labels: national debt, risk

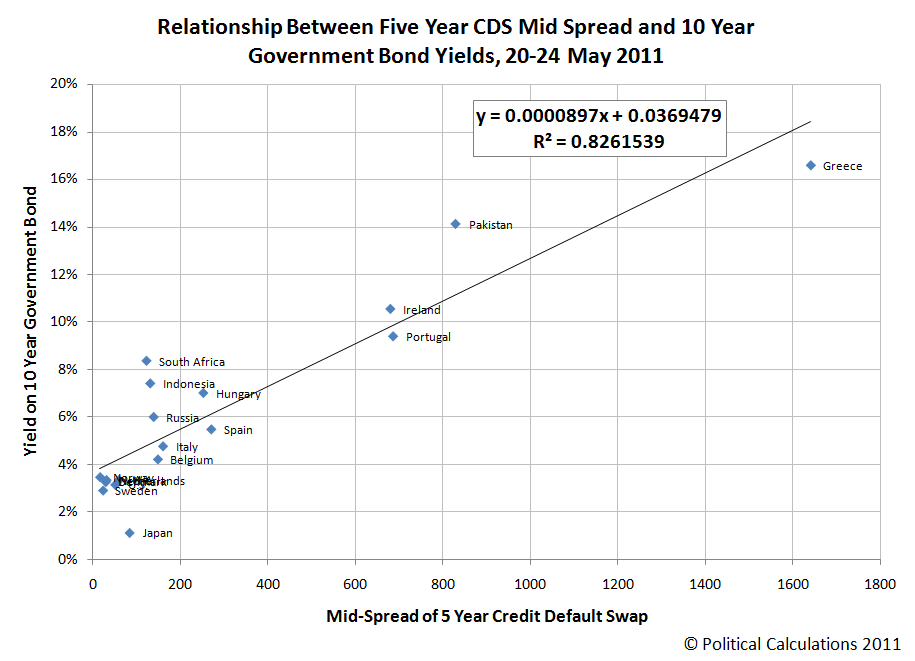

Now that we've connected the dots between the CDS (Credit Default Swap) spreads on government-issued bonds and the probability that the government will default on that debt in the near future, how does that risk tie into the yields on the bonds?

It's not like bond investors are clueless in the situation where a government might not make good on its debt. Although Credit Default Swaps have only become well known since the 1990s, bond investors have had to be on the watch for potentially deadbeat governments for centuries.

So they've come to do what lenders do when they make deals with people who have a higher probability of running out on their obligations. They charge them higher interest rates. And the more likely the borrower might run out on them, the higher the interest rate they charge.

The same is true for governments. The chart below shows what we found when we matched the 10-Year government bond rate for a number of nations with the 5-Year CDS mid-spread values, both of which we recorded during the period from 20 through 24 May 2011:

Now, here's where it gets interesting! The key part of the linear equation we found is the slope (the value multiplied by x). If we invert the slope, we find that a 90-110 point rise in the CDS spread generally corresponds to a 1% increase in the amount of the interest rate that governments must provide to investors as a condition of being able to borrow the money.

Or in other words, if a country sees its CDS spread rise by 90-110 points, which likely corresponds to an increase the probability that it will default on its debt, we should see the interest rates on the 10-year bonds it issues go up by roughly 1%, as investors seek to secure greater returns before the default might take place. Likewise, if a country's CDS spread falls by 90-100 points, the yield on its bonds should go down by roughly 1%.

The effective default risk free rate can be read directly as the value of the y-intercept. For this selection of nations, it's roughly 3.7%.

The risk of default however is not the only factor that interest rates take into account. There's also the risk of rising inflation over the period for which the government is issuing debt. In the chart above, we can identify those nations where inflation is significant by seeing how far above the line they are (in the case of South Africa, Pakistan and Indonesia, while governments far below the line are more likely at risk of deflation, such as Japan has been for an extended period of time.

Given that inflation is more prevalent than deflation in the world, we can't say the same thing for nations that are just below the line, as the linear regression itself would be shifted upward over what would be the case for a non-inflationary world.

As a result, we would instead interpret these nations as having relatively low inflationary prospects, which currently applies in the United States, which is mixed in with the jumble of Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands and the U.K. in the lower left corner of the chart.

Labels: national debt, risk

How likely is it that a country will default on part or all of its national debt in the next five years?

That's a question that we can use the reported spreads in Credit Default Swaps (CDS) for debt issued by sovereign nations to answer!

Since credit default swaps are a kind of insurance policy that only pays out if a borrower defaults against the owner of the debt, the cost of these financial instruments will depend greatly upon the likelihood of a default occurring.

That question is immediately relevant for nations like Greece and Venezuela, both of which are above the critical 50% threshold for five-year CDS spreads, suggesting that both are very likely to default on their government's debt within the next five years.

Unfortunately, that question also applies to a number of other nations that are going through severe financial crises that are pushing them up the a debt-driven "wall of worry". But how can we use the CDS spread data that we can find on the web to estimate what the odds are that the country in question will go into default?

We've sampled CDS spread data from CMA DataVision on 21 May 2011, which we used to reverse engineer a formula to estimate the cumulative probability that a nation will default on its government-issued debt within the next five years, which we've presented in the chart below:

We next built a tool using the relationship we found so that you can estimate a country's likelihood of defaulting upon its national debt if you only know the mid-spread value of the Credit Default Swaps for the next five-year period that have been issued against it.

Some quick notes. First, since we sampled the data to create our default probability model on 21 May 2011, our tool's results are best considered as being in reference to the world's financial situation on that date.

Second, the value of CDS spreads don't just take a nation's default likelihood into account. Vincent Ryan at CFO.com reports that CDS' can also reflect considerations such as "market liquidity, counterparty risks, and technical factors, such as the high leverage inherent in swaps that apply to the CDS itself", which means that just a straight reading of the value may overstate the probability of default to some extent.

Third, and finally, we only had the data going up as far as Greece, which makes the portion of our model that projects beyond the default probability for that nation potentially less accurate than the portions of the CDS values for which we do have data.

The way we figure it though is that if we're talking about a nation that's in a worse situation than Greece on 21 May 2011, the accuracy of the calculation of the nation's probability of default is perhaps the last thing with which people should be concerned. You're more than likely well past the point of "if" and should instead be considering "when."

Image Credit: Fidelity

Labels: national debt, risk, tool

From a discussion forum on the Diabetes Daily web site, on the topic of Sliding Scales, which is a kind of regimen recommended by general practitioners (GP) that many diabetics follow to manage their blood glucose (BG) levels throughout the day:

robcon: Why do some people not like sliding scales in the world of Diabetes management ?

coravh: Because typically they are less precise. I know the ranges my doc gave me first of all didn't work and secondly were too large. For example, from 150 to 200 take x units. It's much more precise (especially when pumping) to know your correction factor (aka insulin sensitivity). In my case, 1 unit brought me down 80 points. So I can actually calculate exactly how much to take based on a precise glucose measurement and not use a one size fits all sliding scale used by docs everywhere.

That's my take on it anyway.

Stump86: Adjusting insulin based on carbs and BG level tends to be more effective at controlling your BG levels than a sliding scale. While sliding scales can be personalized they tend to be one size fits all, and with D, nothing is one size fits all. Being able to adjust your doses is pretty important for success. Unless you always eat and do the same things, a little bit of flexibility is desired, and often necessary, and sliding scales don't always offer that.

Gord: Was in hospital in January for open heart surgery. Endo in hospital decided I should go on Insulin.........no problem with that since my GP and I were already in agreement before surgery.

Problem came when Endo gave me a fixed dose of Lantus daily and a sliding scale of Novolog based upon what my bs reading was PRIOR to meals.

No account was made for what I was about to eat.

Needless to say, I found my PP bs readings all over the place..........hypos due to too much Insulin was worst case.

My GP told me to start "tweaking things" to see what happened.

When I took control and started bolusing to my meter AND what I was about to consume, readings became much more stable.

Jollymon: Maybe some people don't like sliding scales becuase they can't do the math? Or maybe they don't want to count the carbs. I really don't know why because they work for me.

Larry007: My endo gave me a sliding scale and my numbers are all over the place. I worked out 1u/17 for my cf but still find it hard to bring the sugars down. This is very frustrating. The sliding scale is worthless from what i have experienced. i just hope it gets better before i start losing toes and other digits.

aloha: Oooh... I hated using the sliding scale method, numbers ALL over the places, highs, lows, highs followed by abrupt lows, and vice-versa. The scale does not take into account what you are eating, how many carbs, how active or lazy your are going to be, types of carbs (and yes, for me it makes a differnce) the "stacking of insulin", oh my, lots of things that just made it work so poorly for me!

I use a handy dandy calculator (scroll down the page a bit, it;s there!) to help me figure out insulin per carbs, and all kinds of extras, and it helps a lot!

deanusa: very interesting calculator.

aloha: I LOVE that calculator Dean, it has made my life so much easier. with that being said though, you still need to know aproximently how much each unit of insulin lowers your gl, as well as how many carbs you can cover personally with each unit, because you know it is different with every person, and, even with the same person at different times of the day! I do love that it does take into consideration your starting number as well as how active you will be. To be honest, that calculator litterly changed my life1

Can you tell I LOVE it? lol

Lloyd: With sliding scale, you are correcting for highs, rather than preventing them from happening.

Not bad for an hour and 19 minutes of our time one morning a couple of years ago, although the real credit should go to Neil Bason, who developed the math behind the tool and who considered so many of the things that ought to be taken into account for such a calculator.

But still, we're happy to find that it's being very well-received by those for whom we suspected would benefit from such a tool, and we thank all of you for making our day today!

Labels: review

Greg Mankiw reacts to the news about where the President is investing his own money these days:

This is surprising:

The Obamas reported total financial assets valued between $2.8 million and $11.8 million in 2010....They report having between $1.1 million-$5.25 million invested in Treasury bills and another $1 million to $5 million in Treasury notes....The Obamas report having between $200,000-$450,000 invested in the Vanguard 500 Index Fund.

In other words, it looks like the president has less than 10 percent of his personal financial assets invested in equities. This is far, far smaller than financial advisers would recommend. (If you are curious, I am at 60 percent equities.) Either the president is not very financially savvy, or he has reason to believe that the future of the U.S. economy is not very bright.

Or maybe he is just too busy to think about it.

We can rule out the idea that the President is too busy to think about his investments given all the interesting pastimes with which he fills his days, perhaps best demonstrated by the presentation of his March Madness brackets this year, which required a significant amount of preparation on the part of the President to discuss the relative strengths of 64 college basketball teams in making his NCAA tournament picks.

So really, the question is really between whether the President lacks financially savvy in avoiding equities in his investment portfolio, or perhaps is exploiting inside knowledge of the business situation facing publicly traded companies in the U.S., by effectively betting against the prospects of American companies doing well in 2011.

Trading based upon inside knowledge is a widespread problem in Washington D.C., where everyone from elected officials and their family members to Congressional staffers and government bureaucrats exploit what they know about the legislation and regulations they craft and enforce to earn disproportionate gains compared to ordinary investors in the markets, an ethical issue that is not resolved by the blind trusts many politicians set up.

But in this case, given what we've shown about the President's personal finances prior to becoming President, we'd have to say once again that Barack Obama is not a smart man where money matters are concerned.

We'll close by pointing you to a fun parable that helps illustrate the President's lack of savvy about money: Barack Obama's Big Mac Attack!

Labels: investing

How much money do teachers unions really need to collect from their members to represent their interests with their employers?

One way we can find out is to see how much money the various branches of the national and state teachers unions have left over after paying the people who work directly for the unions themselves, whose jobs are to represent the member teachers at their school districts and perhaps also to represent their interests at the state and national level as well.

With that in mind, any money collected from mandatory union dues that sharply exceeds the costs of compensating the union's own employees or the costs of operating the union itself, such as rent for office or meeting space for the union's employees, would have to be considered to be excessive. If excessively excessive, the amount of dues above that basic level would constitute gouging on the part of the union bosses, who set the level of their represented teachers' dues, as they would be collecting far more in dues than what is genuinely necessary to represent their members' at their employers.

The dynamic table we're presenting below takes data compiled by the Education Intelligence Agency from the National Education Association (NEA) and its state affiliates. You can sort the data presented in the table according to the category given in each of the column headings, either from low to high or from high to low by clicking the column heading a second time. If you're accessing this table from one of our RSS feeds, you'll need to click through to our site to take full advantage of the dynamic table's sorting capability.

| U.S. Education Union Revenues and Employee Compensation by State, 2008-09 |

|---|

| State or Entity | Union Affiliate | Total Revenue [1] | Revenue from Member Dues | Employee Compensation [2] | Surplus Revenue [3] | Surplus Revenue [Percent of Member Dues] | Political Party in Control [4] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | National Education Association (National HQ) | 366,933,105 | 352,393,169 | 118,553,883 | 233,839,286 | 63.7% | Democratic |

| Alabama | Alabama Education Association | 20,624,711 | 15,464,423 | 10,296,776 | 5,167,647 | 25.1% | Democratic |

| Alaska | NEA Alaska | 6,563,919 | 5,555,513 | 3,717,042 | 1,838,471 | 28.0% | Split |

| Arizona | Arizona Education Association | 10,153,905 | 8,316,766 | 6,368,492 | 1,948,274 | 19.2% | Republican |

| Arkansas | Arkansas Education Association | 4,455,217 | 3,952,091 | 2,938,202 | 1,013,889 | 22.8% | Democratic |

| California | California Teachers Association | 176,868,803 | 178,923,363 | 83,373,700 | 95,549,663 | 54.0% | Democratic |

| Colorado | Colorado Education Association | 11,547,934 | 10,479,538 | 6,641,638 | 3,837,900 | 33.2% | Democratic |

| Connecticut | Connecticut Education Association | 18,096,257 | 17,273,742 | 14,961,202 | 2,312,540 | 12.8% | Democratic |

| Delaware | Delaware State Education Association | 4,806,832 | 3,934,655 | 2,763,703 | 1,170,952 | 24.4% | Democratic |

| Florida | Florida Education Association | 30,562,586 | 25,235,581 | 12,384,364 | 12,851,217 | 42.0% | Republican |

| Georgia | Georgia Association of Educators | 9,573,040 | 7,660,449 | 6,091,621 | 1,568,828 | 16.4% | Republican |

| Hawaii | Hawaii Sate Teachers Association | 7,684,800 | 6,882,900 | 4,247,781 | 2,635,119 | 34.3% | Democratic |

| Hawaii | University of Hawaii Professional Assembly | 3,345,352 | 3,173,552 | 960,866 | 2,212,686 | 66.1% | Democratic |

| Idaho | Idaho Education Association | 5,206,116 | 4,177,234 | 3,262,721 | 914,513 | 17.6% | Republican |

| Illinois | Illinois Education Association | 48,327,911 | 42,345,994 | 50,016,259 | -7,670,265 | -15.9% | Democratic |

| Indiana | Indiana State Teachers Association | 21,644,245 | 19,634,746 | 20,485,393 | -850,647 | -3.9% | Split |

| Iowa | Iowa State Education Association | 14,317,046 | 12,608,093 | 9,435,891 | 3,172,202 | 22.2% | Democratic |

| Kansas | Kansas NEA | 8,697,391 | 7,653,602 | 6,351,306 | 1,302,296 | 15.0% | Republican |

| Kentucky | Kentucky Education Association | 11,393,174 | 9,740,133 | 6,668,526 | 3,071,607 | 27.0% | Split |

| Louisiana | Louisiana Association o fEducators | 3,923,728 | 2,921,692 | 2,323,359 | 598,333 | 15.2% | Democratic |

| Maine | Maine Education Association | 7,752,189 | 5,836,496 | 5,410,294 | 426,202 | 5.5% | Democratic |

| Maryland | Maryland State Education Association | 18,678,952 | 16,440,085 | 11,755,639 | 4,684,446 | 25.1% | Democratic |

| Massachusetts | Massachusetts Teachers Association | 40,035,184 | 36,164,880 | 21,125,727 | 15,039,153 | 37.6% | Democratic |

| Michigan | Michigan Education Association | 78,138,236 | 65,771,358 | 55,389,591 | 10,381,767 | 13.3% | Split |

| Minnesota | Education Minnesota | 29,813,071 | 28,378,324 | 18,484,680 | 9,893,644 | 33.2% | Democratic |

| Mississippi | Mississippi Association of Educators | 2,225,990 | 1,274,502 | 1,372,860 | -98,358 | -4.4% | Democratic |

| Missouri | Missouri NEA | 9,521,574 | 7,332,243 | 5,938,215 | 1,394,028 | 14.6% | Republican |

| Montana | MEA-MFT | 6,169,856 | 5,000,859 | 3,668,112 | 1,332,747 | 21.6% | Split |

| Nebraska | Nebraska State Education Association | 8,697,451 | 7,255,736 | 4,841,960 | 2,413,776 | 27.8% | Republican |

| Nevada | Nevada State Education Association | 9,455,151 | 7,661,368 | 3,729,526 | 3,931,842 | 41.6% | Democratic |

| New Hampshire | NEA New Hampshire | 6,391,083 | 5,297,637 | 4,314,136 | 983,501 | 15.4% | Democratic |

| New Jersey | New Jersey Education Association | 112,152,523 | 104,075,758 | 45,357,538 | 58,718,220 | 52.4% | Democratic |

| New Mexico | NEA New Mexico | 3,155,126 | 2,033,113 | 1,850,301 | 182,812 | 5.8% | Democratic |

| New York | New York State United Teachers | 125,156,340 | 109,122,676 | 77,329,394 | 31,793,282 | 25.4% | Democratic |

| North Carolina | North Carolina Association of Educators | 11,161,779 | 9,399,136 | 7,629,623 | 1,769,513 | 15.9% | Democratic |

| North Dakota | North Dakota Education Association | 2,767,791 | 1,925,401 | 1,539,293 | 386,108 | 14.0% | Republican |

| Ohio | Ohio Education Association | 59,252,311 | 56,664,971 | 26,642,028 | 30,022,943 | 50.7% | Split |

| Oklahoma | Oklahoma Education Association | 8,111,500 | 6,164,071 | 4,005,152 | 2,158,919 | 26.6% | Republican |

| Oregon | Oregon Education Association | 22,016,164 | 18,689,618 | 23,264,534 | -4,574,916 | -20.8% | Democratic |

| Pennsylvania | Pennsylvania State Education Association | 64,727,092 | 54,856,881 | 36,075,940 | 18,780,941 | 29.0% | Split |

| Rhode Island | NEA Rhode IslanDemocratic | 4,064,571 | 3,176,651 | 3,052,203 | 124,448 | 3.1% | Democratic |

| South Carolina | South Carolina Education Association | 2,488,068 | 1,634,617 | 1,289,881 | 344,736 | 13.9% | Republican |

| South Dakota | South Dakota Education Association | 2,460,289 | 1,674,654 | 1,348,401 | 326,253 | 13.3% | Republican |

| Tennessee | Tennessee Education Association | 12,074,558 | 11,286,837 | 8,503,148 | 2,783,689 | 23.1% | Republican |

| Texas | Texas State Teachers Association | 11,230,446 | 8,166,469 | 6,276,107 | 1,890,362 | 16.8% | Republican |

| Utah | Utah Education Association | 3,400,957 | 2,746,270 | 2,046,444 | 699,826 | 20.6% | Republican |

| Utah | Utah School Employees Association | 1,815,927 | 1,317,564 | 906,304 | 411,260 | 22.6% | Republican |

| Vermont | Vermont NEA | 4,127,296 | 3,117,944 | 2,864,875 | 253,069 | 6.1% | Democratic |

| Virginia | Virginia Education Association | 15,211,783 | 12,398,133 | 10,908,364 | 1,489,769 | 9.8% | Split |

| Washington | Washington Education Association | 32,773,708 | 27,445,668 | 32,878,313 | -5,432,645 | -16.6% | Democratic |

| West Virginia | West Virginia Education Association | 3,250,276 | 2,640,051 | 1,794,604 | 845,447 | 26.0% | Democratic |

| Wisconsin | Wisconsin Education Association Council | 25,480,973 | 23,458,810 | 14,382,812 | 9,075,998 | 35.6% | Democratic |

| Wyoming | Wyoming Education Association | 3,370,689 | 2,440,382 | 1,581,344 | 859,038 | 25.5% | Republican |

| Military | Federal Education Association (DoD Schools) | 2,411,815 | 2,119,056 | 1,042,094 | 1,076,962 | 44.7% | N/A |

Observations

The key data in the table above is found in the Surplus Revenue [Percent of Member Dues] column. Here, the mean and median "surplus" percentage was 22.1% and 22.4% respectively.

Using these mean and median figures as a baseline value, we identify any union affiliate with a surplus percentage of member dues greater than 25% of the total member dues collected as potentially having set their member dues in excess of that required to legitimately represent the interests of teachers at their employers. We've shaded the rows of the table where the union affiliate's surplus dues exceed this level.

We also note several union affiliates that appear to have been substantially mismanaged in 2008-09, in that their expenditures for compensating their direct employees exceed the revenue collected by dues imposed upon their union's member teachers. The states that fall in this category include Illinois, Indiana, Mississippi, Oregon and Washington. The rows for these states have been shaded red in the table above.

But to answer the question we asked at the outset, some teachers are indeed being gouged by their union's bosses - the ones whose state legislatures were controlled by the Democratic party in 2008-09 and whose union bosses are sending the member teachers' money. The amount of the gouging would be approximately the amount in excess of 25% of each education union affiliate's total revenue from their members' dues.

We see that at the national level, where surplus member dues exceed 63% of the total member dues collected. Using our 25% threshold as the cap for "legitimate" union representation expenses, this suggests that the portion of teachers union dues that go to the national affiliate of the NEA could be reduced by 40% without impacting the ability of the teachers to have their interests effectively represented at this level.

The states whose education unions are most gouging their teachers members include Hawaii (with surplus member dues of 66% and 34% for the state's two NEA affiliates), California (54%), New Jersey (52.1%), Ohio (50.7%), Florida (42.0%), Nevada (41.6%), Massachusetts (37.6%) and Wisconsin (35.6%). At a minimum, teachers' union dues could be reduced by anywhere from 10% to 25% in these states without impacting the union affiliates ability to just represent the teachers at their employers.

Finally, we note a significant divergence between states with legislatures controlled by members of the Democratic party and those states whose legislatures are either controlled by the Republicans or are split between the two major U.S. political parties.

Here, after adding up the amount of surplus revenue remaining after the union affiliates employees compensation has been subtracted from the total member dues collected, we find that states with Democratic legislatures account for $237,616,324 of the total surplus dues collected, or 70.7% of the $335,937,045 of the total surplus member dues collected in 2008-09 for the NEA's state affiliates.

By contrast, union affiliates in states with divided legislatures account for $66,067,598, or 19.7% of the total surplus collected, while union affiliates in states with legislatures controlled by the Republican party have surplus member dues collections of $32,253,123, or 9.6% of the total surplus collected among all states.

We should note that these figures might be even more disproportionately weighted toward states whose legislatures were controlled by the Democratic Party, if not for the five states where the teachers union affiliates operated in the red.

There are some different ways to interpret what this divergence means. First, it could indicate that teachers in states with legislatures with at least one division of the state legislature controlled by the Republican party are happier with that situation, as it indicates that the teachers aren't massing funds to support a prolonged strike in those states. That would also mean that teachers in states with Democratic-party controlled legislatures are less happy with that situation, and that they were preparing to support massive walkouts in 2008-09.

Yes, we laughed at that idea too! More likely, what's going on is that the teachers unions in states with Democratic party-controlled legislatures have been effectively captured by Democratic party members, who are using the surplus member dues to fund their party's political candidates at all levels in those states.

But we'd love to see the reaction of the state union bosses with high levels of dues gouging if anyone ever asks them if the reason why union dues would seem to be so much lower in the so-called Republican-controlled states is because Republicans are better at keeping unionized teachers happy!

Elsewhere on the Web

Marginal Revolution's Alex Tabarrok highlights some interesting quotes by former teacher's union boss Albert Shanker in pointing to an article by Joel Klein in The Atlantic on the failure of American schools.

Previously on Political Calculations

- How Much Do Public School Teachers Really Make Compared to Private School Teachers?

- The Math They Forgot or, More Likely, Were Never Taught

- Ranking School Smarts by Major, Updated

- The Educated and the Unemployed

- The Contribution of Student Loans to the U.S. National Debt

- U.S. Spending for Higher Education Since 1962

- Forecasting the Cost of College

- Correlating Federal Spending and College Tuition

- Who's Behind the U.S. Higher Education Bubble?

- Visualizing the U.S. Higher Education Bubble

- How Much Money Will You Earn in Your Lifetime?

- What Kind of Job Can You Hope to Get With Your Education?

- Does It Pay to Go to Law School?

- The Eureka Experiment

- Milking the Cash Cows of College

- Should You Send Your Child Away to College?

- Highly Questionable Higher Education Costs

- Subsidizing Low Value Majors

- Keeping the Cost of College Down

- Does Financial Aid Drive College Costs Up?

- Math, Science, Students, Teachers

- Your Student Loan

- The Transformation of Student Loans Into Taxes

- Saving for College

Notes for the Table

[1] Total Revenue combines member dues with investment gains or losses.

[2] Compensation includes the cost of wages, payroll taxes, pension contributions and other benefits paid on behalf of individual employees. Travel and similar tax-deductible expenses are not included. We should also note that the Education Intelligence Agency indicates that some union affiliates (e.g. Michigan) would appear to have included retirees and/or others in their employee compensation totals.

[3] Surplus Revenue is calculated by subtracting Employee Compensation expenses from Revenue from Member Dues.

[4] The political party in control refers to the political party with majorities in the state or national legislature. This information was obtained from Larry Sabato's Crystal Ball web site.

Labels: education, jobs, politics

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.