Political Calculations' initial estimate of median household income in May 2020 is $65,669, down 0.5% from April 2020's initial estimate of $66,027.

The change is primarily the result of the aggregate loss of wage and salary income recorded for the month as a continuing consequence of the business closures and stay-at-home orders imposed by state and local governments in response to the outbreak of the coronavirus pandemic in the U.S. in March 2020, which has resulted in large scale job losses. Though many of these orders began to be lifted around the U.S. during May 2020, many local jurisdictions are still impose restrictions that contribute to both lost incomes and lost jobs, which slow economic recovery in addition to weighing on the median household income estimate.

While this figure is based on the Bureau of Economic Analysis' current estimates of aggregate personal income, we think the BEA is still underestimating both the extent of job loss and the amount of lost wage and salary income being experienced by millions of Americans, particularly in lower income-earning occupations. We anticipate the BEA will revise its estimates for the month lower in future months as it replaces projections based on pre-coronavirus recession trends with actual income data as it becomes available.

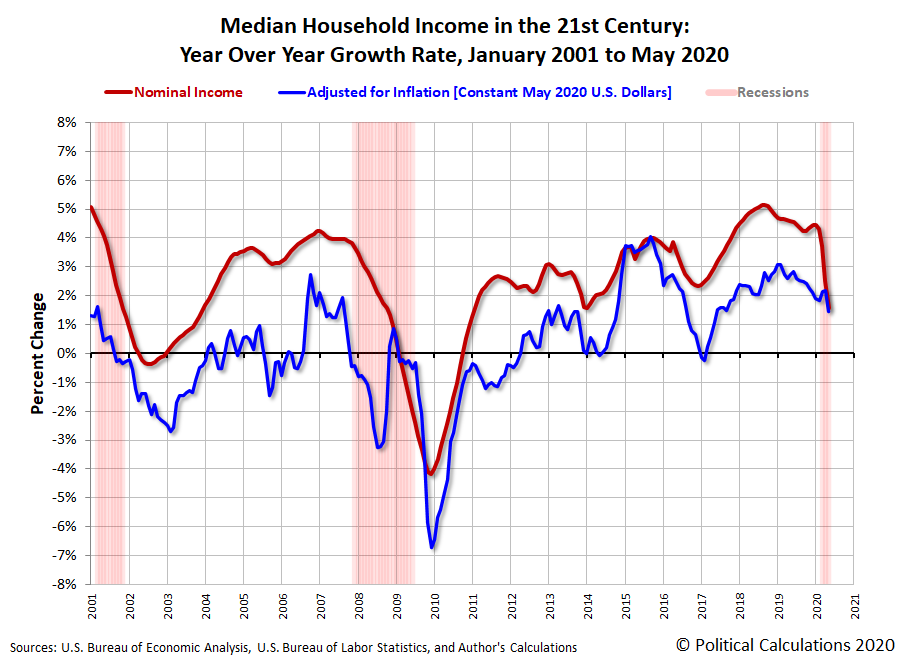

The following chart shows the nominal (red) and inflation-adjusted (blue) trends for median household income in the United States from January 2000 through May 2020. The inflation-adjusted figures are presented in terms of constant May 2020 U.S. dollars.

Median household income in the U.S. has declined by 1.4% from the revised $66,627 recorded in February 2020, the last month of expansion for the U.S. economy identified by the National Bureau of Economic Research, which marks the onset of the coronavirus recession.

Looking at the year-over-year rate of change for median household income, the following chart confirms the nominal trend has nosed over and has continued sharply decelerating at the fastest rate recorded to date in the 21st century.

Looking ahead, we're starting to see large scale layoffs in the aerospace sector, particularly for the commercial transport portion of the industry, with Boeing having already announced 6,770 job cuts and Airbus just announcing it will be cutting its production by 40%. The effects of the loss of these comparatively high paying jobs should start showing up in the data next several months, where we should recognize the impact will extend through their suppliers, which includes thousands more jobs across the U.S.

Analyst's Notes

The peak value for nominal median household income of $66,627 in February 2020 has been revised very slightly up from our previous estimate of $66,626. We anticipate the aggregate personal income data we use in generating our estimates will be subject to substantial revision given the extent of the coronavirus recession's disruption to the U.S. economy.

Since our estimates are tied to that data, until those revisions occur, we think our estimates will overstate the level of median household income in the U.S. until the economic situation stabilizes.

Other Analyst's Notes

Sentier Research suspended reporting its monthly Current Population Survey-based estimates of median household income, concluding their series with data for December 2019. In its absence, we are providing the estimates from our alternate methodology. Our data sources are presented in the following section.

References

Sentier Research. Household Income Trends: January 2000 through December 2019. [Excel Spreadsheet with Nominal Median Household Incomes for January 2000 through January 2013 courtesy of Doug Short]. [PDF Document]. Accessed 6 February 2020. [Note: We've converted all data to be in terms of current (nominal) U.S. dollars.]

U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Price Index, All Urban Consumers - (CPI-U), U.S. City Average, All Items, 1982-84=100. [Online Database (via Federal Reserve Economic Data)]. Last Updated: 10 June 2020. Accessed: 10 June 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 2.6. Personal Income and Its Disposition, Monthly, Personal Income and Outlays, Not Seasonally Adjusted, Monthly, Middle of Month. Population. [Online Database (via Federal Reserve Economic Data)]. Last Updated: 26 June 2020. Accessed: 26 June 2020.

U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Table 2.6. Personal Income and Its Disposition, Monthly, Personal Income and Outlays, Not Seasonally Adjusted, Monthly, Middle of Month. Compensation of Employees, Received: Wage and Salary Disbursements. [Online Database (via Federal Reserve Economic Data)]. Last Updated: 26 June 2020. Accessed: 26 June 2020.

Labels: median household income

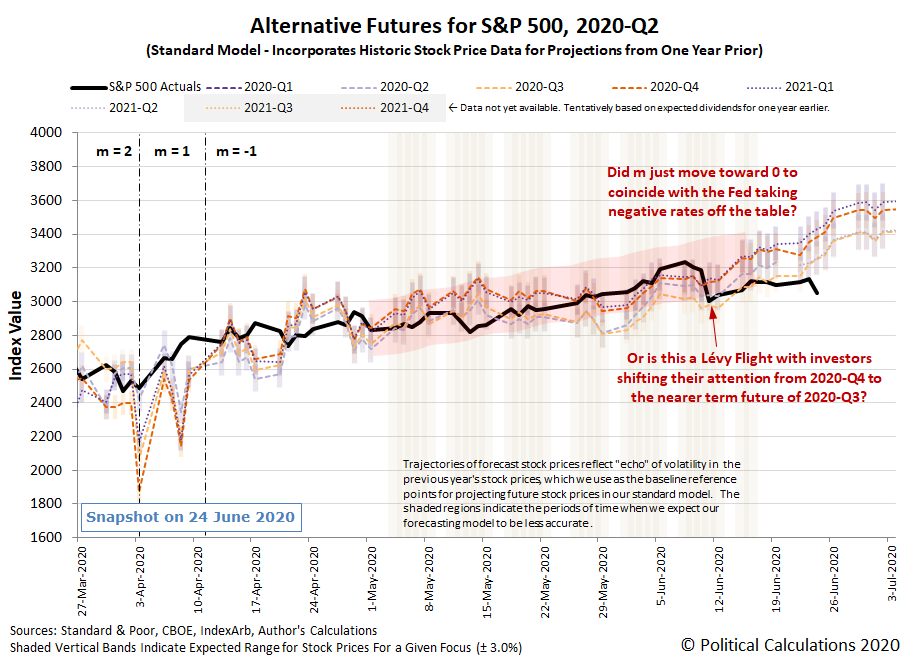

As expected, answers to the questions we asked last week were forthcoming, allowing us to eliminate one of the two primary hypotheses we raised for what caused the S&P 500 (Index: SPX) to suddenly drop 5.9% on 11 June 2020.

The first hypothesis was that S&P 500 shifted their time horizon from 2020-Q4 to 2020-Q3, without any change in expectations for how expansionary the Fed's monetary policies would be, which is consistent with the first version of the alternative futures chart for 2020-Q2:

For this hypothesis to hold, we would have needed to see the trajectory of the S&P 500 track along with the expectations associated with investors focusing their forward-looking focus on 2020-Q3. We also indicated what we might expect to see if this hypothesis failed:

... if the shift that occurred on 11 June 2020 was the result of a change in expectations for the Fed's monetary policies, where the amplification factor in the dividend futures-based model suddenly changed to become less negative than it has been, we will see the trajectory of the S&P 500 start to consistently underrun the levels projected by the model as shown on the alternative futures chart above, which currently assumes no change in the amplification factor since 12 April 2020.

And that's indeed what happened, which allows us to reject this first hypothesis.

In the remaining hypothesis, we assume investors have incorporated the new expectation the Fed's monetary policies will be less expansionary going forward than they had previously anticipated, which we're showing in the change of the value of the dividend futures-based model's amplification factor (m) from -1 to 0:

There's a second variation of this hypothesis that assumes there was also a Lévy Flight event with investors shifting their attention inward from 2020-Q4 toward 2020-Q3, but we're unlikely to ever untangle that possibility with the limited data we have available.

That's because both these variations are consistent with what we observed in the last week, up until 24 June 2020. That date coincides with when we think another adjustment occurred to further rein in expectations for how expansionary the Fed's monetary policies will be going forward, which we see as a change in the amplification factor in the dividend futures-based model. We think the new value has risen to now fall somewhere between 1 and 1.5.

In the next version of the alternative futures chart, we show the amplification factor changing from 0 to 1 on 24 June 2020, where we assume investors have sustained their focus on 2020-Q4 since 4 May 2020.

Let's present one more new scenario. Here, let's show the amplification factor changing from 0 to 1.5 on 24 June 2020, but now, we'll assume that investors shifted their forward-looking time horizon from 2020-Q4 to 2020-Q3 on Friday, 26 June 2020.

We don't yet know which of these new scenarios might better explain how the S&P 500 behaved last week. But at the very least, we have new hypotheses and variations we can test with observations, which is a big part of what we do behind the scenes when we develop our analysis. We want to give you a sense of what that work is like with this latest edition of the S&P 500 chaos series, which we hope you find useful in developing your own insights.

Let's now recap the main market-driving news headlines from the week that was....

- Monday, 22 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil up above 2% on tighter supplies, eased lockdowns

- U.S. housing set to ride out the pandemic's economic storm: Reuters poll

- Small, medium businesses feel brunt of lockdown pain: survey

- Mixed picture emerging for global recovery:

- Global dollar crunch appears over as central banks rely less on Fed backstop

- Soft underbelly in China's steel sector boom points to bumpier economic recovery

- Bigger stimulus developing in U.S., Mexico:

- Trump backs more aid for Americans amid coronavirus: Scripps

- Mexico central bank seen cutting rates 50 basis points, inflation forecast to tick up: Reuters poll

- ECB, EU minions don't want to lose control:

- ECB money-printing shouldn't become 'unbound', says Weidmann

- Germany's Scholz avoids pledge to stick to debt brake next year

- ECB's de Guindos sees risk of reopening too soon after lockdown

- Fed minions consider future for U.S. economy, monetary policy:

- Fed's Rosengren sees difficult second half for U.S. economy

- 'Yield curve control' meant less market intervention in Japan: NY Fed

- Oil, stocks gain, but rising infection rates spark concerns

- Tuesday, 23 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil flat, near highest since March, after Trump assurance on China trade

- Euro rises on upbeat data, Trump says China trade deal still intact

- China has picked up its 'game' on trade with U.S., Trump adviser says

- U.S. economy improving; rising COVID-19 cases a threat

- U.S. business sector contraction eases in June

- Fed minion says Fed's policies not making inequality worse:

- Signs and portents in the Eurozone:

- Euro zone downturn eased in June, V-shaped recovery in doubt

- German economy to shrink by 6.5% this year due to coronavirus: economic advisors

- EU to focus on rebuilding after pandemic in next 18 months: Germany

- Wall Street ends higher on recovery hopes, Nasdaq hits another record

- Wednesday, 24 June 2020

- Oil dives over 5% as U.S. crude stocks hit record, COVID cases mount

- Bigger trouble developing in Brazil:

- Bigger stimulus developing in the U.S., Japan:

- Exclusive: New U.S. development agency could loan billions for reshoring, official says

- BOJ offers $78 billion to firms hurt by pandemic in first phase of loan programme

- Fed minions look into future, unhappy with past.

- Fed's Evans: U.S. recovery to take years, outbreaks to slow growth

- Fed's Bullard: U.S. needs 'structural' responses to lack of Black economic progress

- Shadows being cast over Eurozone:

- ECB's De Cos calls for EU recovery fund to be approved as soon as possible

- Don't get too excited by solid euro zone data, ECB's Lane says

- Europe's emergency loan schemes stir fears of a debt trap

- Wall Street finishes lower on rising virus cases, weak economic view

- Thursday, 25 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil prices climb as U.S. economic data lends support

- Fed balance sheet down again as currency swaps fall further

- The rate of growth of the Fed's balance sheet has been a factor in driving the coronavirus stock market rally, in the current environment and the absence of a solid recovery, if it slows down or reverses, indicating a less expansionary monetary policy for investors, a number of analysts believe stock prices will follow.

- Bigger trouble developing in the Eurozone:

- Euro zone data confirm tepid recovery, ECB's Knot says

- ECB can hold back on bond buys if markets calm, Mersch says

- How the ECB's minions will get permission to provide bigger stimulus:

- ECB found 'pragmatic' solution to German legal dispute, Rehn says

- Changing of guard at top German court signals de-escalation for ECB

- Fed minions advance gloomy outlook:

- Fed's George says full economic recovery is still far off

- Fed's Bostic: Even gradual second wave could force consumers back indoors

- Fed's Kaplan says lower-educated workforce could struggle to adapt to post-coronavirus economy

- Wall Street ends choppy session higher as strength in banks offsets virus woes

- Friday, 26 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil dips on rise in U.S. coronavirus cases, set for weekly fall

- Fed's Bostic warns of 'pain' with summer end to government aid

- U.S. consumer spending rebounds; falling income, surging COVID-19 cases loom

- U.S. on track for economic rebound despite virus 'interruptions', Commerce secretary says

- Bigger trouble developing in Japan, Mexico:

- Japan's May factory output, retail sales to extend slump as coronavirus bites: Reuters poll

- Mexican economy shrinks record 17.3% in April as industry swoons

- Bigger stimulus developing in the Eurozone:

- ECB minions pushing out and pushing for more stimulus

- Euro zone bank lending continues to surge amid crisis, ECB says

- ECB is better safe than sorry with easy policy, Rehn says

- We're past the worst, but recovery will be uneven, ECB's Lagarde says

- Wall Street ends lower as coronavirus surge prompts renewed restrictions

Barry Ritholtz summarized the positives and negatives he found in the week's markets and economy news.

This upcoming trading week will be shortened by the Independence Day holiday, but we'll be back to recap the week next Monday....

Have you ever been flummoxed by a screw that defies all your efforts to remove it after you've stripped its head?

While there are specialized tools or creative methods you can use to extract a screw with a stripped head, the specialized tools can only work if you happen to have them, and the creative methods you might otherwise use can be pretty frustrating unless you happen to be lucky with your specific stripped screw circumstances. Wouldn't it be nice if you could just pull a regular hand tool out of your toolbox to do the job?

In the case of stripped screws with a raised heads, there might now be a reliable option to do just that. From Japan, Engineer Inc.'s patented Neji-saurus PZ-59 pliers have dinosaur-inspired jaws that give it unique capabilities, as shown in the company's promotional video for the product, which is itself awesomely awesome.

Engineer's dinosaur jaw-inspired family of pliers is marketed in the U.S. by Vampire Professional Tools under the brand name VamPLIERS. According to Core77, Engineer Inc. has sold over 4 million of its Neji-saurus pliers worldwide since inventing them in 2002.

Other Inventive Hand Tools

Labels: technology

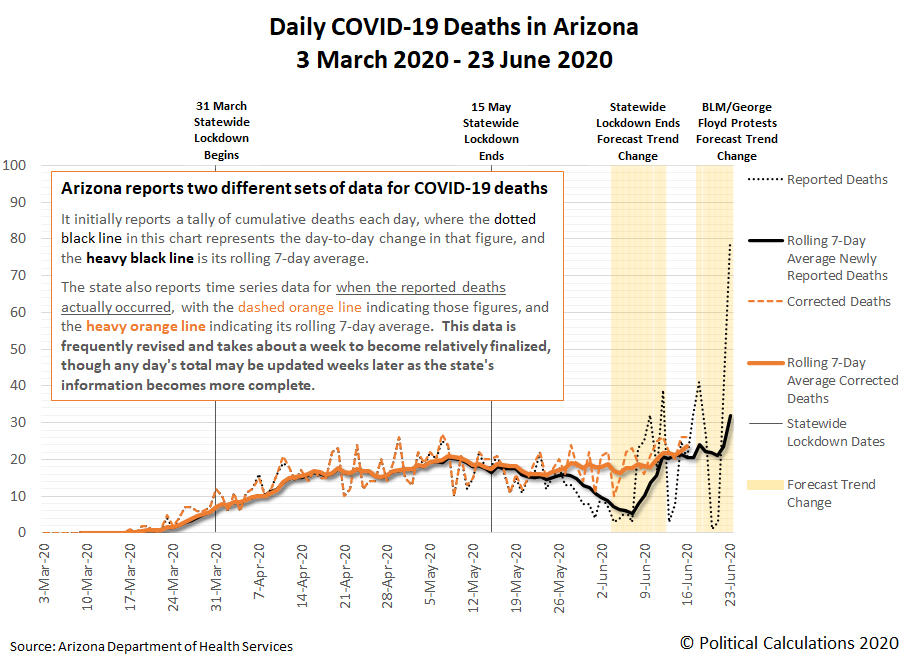

Following our reporting that Arizona has become the new epicenter for coronavirus cases in the U.S., we've been paying close attention to the number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 infections in the state. We've found the state is reporting two sets of data for those deaths.

The first is a cumulative daily tally of reported deaths that many news outlets use in their reporting, from which a day-to-day change in the number of these newly reported cumulative deaths may be calculated.

But the day-to-day changes in the cumulative total doesn't communicate when these deaths actually occurred. For that data, Arizona's Department of Health Services is reporting time series data on its COVID-19 dashboard, in the Deaths section, as a bar chart that is updated and revised daily. From what we have observed, it takes about a week for a given day's death tally to be relatively finalized, after which it may still be subject to revision as the state's information about their actual timing becomes more complete.

In the following chart, we've taken data from both series to see how they compare to each other, where we've discovered that the day-to-day changes in the cumulative tally may be providing an unreliable picture of the timing of COVID-19 deaths in Arizona.

The biggest deviation occurs within the timeframe we've previously projected would show a change in trend following the lifting of Arizona's statewide lockdown order, where instead of declining then rising sharply in the predicted range, COVID-19 deaths instead occurred at a relatively steady pace before ticking upward in the predicted range.

Based on what we're seeing in the more accurate time series data, the reopening of Arizona's economy had a small effect on the number of COVID-19 deaths taking place 20 to 28 days later, with the state experiencing a slow uptrend in deaths, as might be expected. This situation is far better than what occurred in states like New York or other states that copied its policies, which saw COVID-19 deaths skyrocket as their number of cases raced past the population-adjusted levels Arizona is now reaching, which is attributable to the different policy choices made by each state's government officials.

We're still short of when we can see what impact the George Floyd protests in the state may have had upon the trend for COVID-19 deaths, where the state's more accurate time series data for these deaths is still very incomplete. We should have a much better picture of the impact of that event within the next one to two weeks.

Labels: coronavirus, data visualization

The new home market in the U.S. is showing surprising resiliency during 2020's coronavirus pandemic.

The following chart shows the trailing twelve month average of the market capitalization of the U.S. new homes, where we see that after last peaking at $21.7 billion in December 2020, the market cap of all new homes sold in the U.S. has ranged between $21.34 billion (March 2020) and $21.45 billion (January 2020) in the five months since, with the initial estimate for May 2020 at $21.38 billion.

That's pretty remarkable because the market for new homes could very well have tanked during the coronavirus recession the way it did when demand collapsed as the first U.S. housing bubble began deflating in 2005-2006.

Instead, the market for new homes in the U.S. has resisted falling the way other industries have, as demand has remained relatively strong. Here's how Reuters described May's sales figures:

Sales of new U.S. single-family homes increased more than expected in May, suggesting the housing market was on the cusp of recovery after being hammered, together with the broader economy, by the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Commerce Department said on Tuesday new home sales jumped 16.6% to a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 676,000 units last month. New home sales are counted at the signing of a contract, making them a leading housing market indicator.

April’s sales pace was revised down to 580,000 units from the previously reported 623,000 units. Economists polled by Reuters had forecast new home sales, which account for about 10% of housing market sales, rising 2.9% to a pace of 640,000 in May.

We would only quibble with Reuters' description of the housing market being "hammered" during the coronavirus pandemic. The historic data confirms the decline in the industry's market cap since December 2019 is almost trivial compared to the housing bubble deflation years. That's what real hammering for a distressed industry looks like!

References

U.S. Census Bureau. New Residential Sales Historical Data. Houses Sold. [Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 23 June 2020.

U.S. Census Bureau. New Residential Sales Historical Data. Median and Average Sale Price of Houses Sold. [Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 23 June 2020.

Labels: real estate

Nearly two weeks ago, in our final weekly update on the progression of the coronavirus pandemic in the United States, we noted that three states were seeing significant increases in the number of new COVID-19 cases: Arizona, Utah, and Oregon. Since then, one of these three states has broken away from the pack for the rate at which it is confirming new cases.

We won't beat around the bush any more. It's Arizona. Here's an interactive chart of the rolling 7-day average of newly confirmed COVID-19 cases per 100,000 residents per day for all 50 states and the District of Columbia from 17 March 2020 through 22 June 2020, where you can easily see Arizona's surge.

Before we continue, take a moment to review the chart to compare Arizona's trajectory with previous leaders for population-adjusted newly confirmed SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus infections, such as New York, New Jersey, Rhode Island, and the District of Columbia.

We wanted to point that out before showing the next interactive chart, which tracks the rolling 7-day average number of deaths attributed to COVID-19 per 100,000 residents per day for the 50 states and the District of Columbia over the same period of time as the first chart.

In this second chart, we can see that Arizona is having a very different experience than the previous leaders for the number of COVID-19 deaths per 100,000 residents, with Arizona's daily average death counts not echoing the trend being set by the state's exploding number of newly confirmed cases as happened elsewhere in the U.S.

That's because unlike New York and other states that copied the Cuomo administration's disturbing policy of forcing nursing homes to admit coronavirus-infected patients, which then ran through those facilities like "fire through dry grass", Arizona's state officials have not, which has kept the state's total count of COVID-19 deaths much lower.

And even though Arizona is now seeing increases in the rate at which state residents are being found to be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus that are comparable to what the states that have previously been epicenters of COVID-19 infections in the United States have experienced, we think it is unlikely that the state will experience a similar level of deaths attributable to COVID-19.

That's because of the age demographics of the state's confirmed coronavirus infections, which over the last month, have shifted considerably with younger residents becoming the most likely to become infected. The following chart shows that transition, where we're comparing the number of new infections confirmed by age group for the period from 7 May 2020 through 12 May 2020 with the data for 18 June 2020, which we selected because the number of cases for the Age 65+ population is very similar and because Arizona's Department of Health Services doesn't make time series data for its COVID-19 age demographics available, which meant we could only work with what little data we could get.

As you can see, over the last month and half, the age demographic profile for Arizona's confirmed COVID-19 cases has shifted heavily toward younger residents, whom the Centers for Disease Control indicates are far less likely to die from the infection.

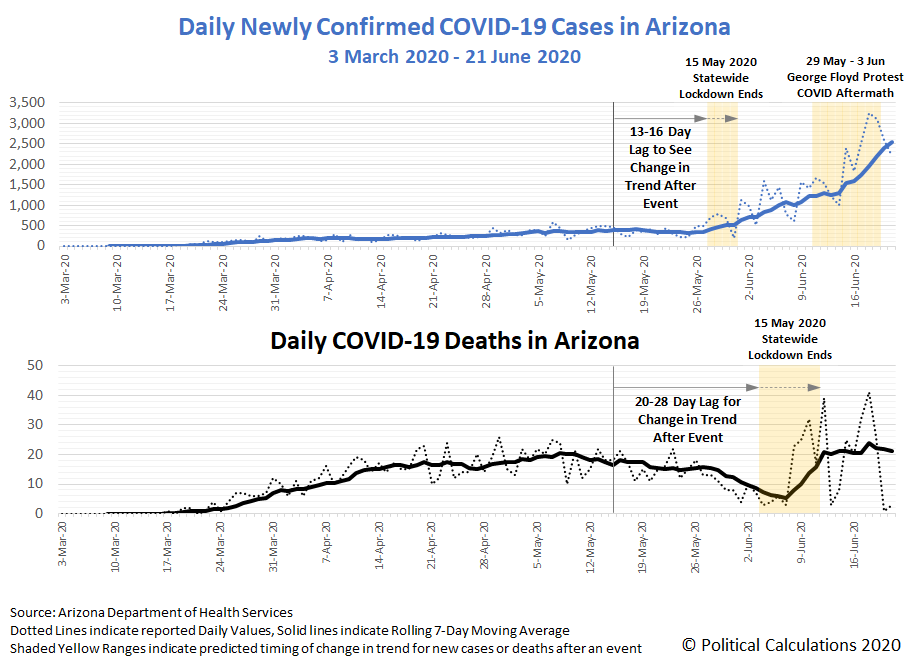

But why is Arizona experiencing such a large increase in the number of new coronavirus cases in the first place? To answer that question, we're going to a forward-calculation method and a backward-calculation method.

For the forward calculation method, we'll start with the established observation that half of those who test positive for COVID-19 will develop symptoms between 5 and 6 days after having been exposed to enough of the virus to become infected by it. Then, because coronavirus testing in Arizona is now taking anywhere from 7 to 10 days to indicate results, which if we use 6 days from exposure to infection as our base before considering the lag to report test results, it takes 13 to 16 days for test results to be reported after the initial exposure.

The backward calculation method is linked to the amount of time a patient who goes on to succumb to COVID-19 dies after they've developed symptoms. Here, an early study found the typical period before death might occur could range between 15 and 22 days, with a median period of 18.5 days after the patient's initial onset of symptoms. Combined with the median time from exposure to the onset of symptoms, that gives an estimated period from infectious exposure to death of anywhere from 20 to 28 days after they were initially exposed.

The next chart shows the rolling 7-day average number of newly confirmed cases and deaths per day in Arizona shows when these methods would predict a change in trend for both might occur following an exposure event. For our analysis, we've used the lifting of Arizona's statewide lockdown order on 15 May 2020 and the George Floyd protests that occurred in Phoenix and other cities in the state between 29 May 2020 and 3 June 2020 as our candidate exposure events.

Noting that the vertical scales on the two charts are very different from one another, we see that the initial upturn in Arizona's incidence of newly confirmed COVID-19 infections and deaths is consistent with the lifting of the state's lockdown order on 15 May 2020. What this outcome suggests is that Arizona had a large number of latent cases percolating within its population that, once businesses began to reopen and the stay-at-home order for residents was lifted, resulted in the resumption of the spread of COVID-19 infections in the state. Combined with the fact the age demographics of who was becoming infected shifted heavily toward younger residents during this time, the two observations suggest the activities in which these individuals engaged immediately following the lifting of the lockdown orders is responsible for the sudden rise in the number of cases in the state.

There's a second exposure event to consider. Over the six days from 29 May through 3 June 2020, numerous protest events took place in Phoenix and other cities around Arizona following the tragic death of George Floyd as he was being arrested in Minneapolis, Minnesota on 25 May 2020. Once again, crowds of predominantly younger people participated in these activities, which older Arizonans generally avoided, concerned with the risk of becoming infected with the coronavirus.

Here, we see the rate at which new COVID-19 infections were confirmed have accelerated following the forward calculation method's 13-16 day lag for a change in trend to appear after this multi-day event, as would be expected.

Meanwhile, we cannot yet confirm the effect with the trend for deaths because not enough time has yet passed for it to become evident with the longer lag of the backward calculation method, although here, because of the age demographics of who participated in the protests skewing so heavily toward younger Arizonans who are much less likely to die from COVID-19, we would anticipate a considerably smaller change in trend than what occurred for the numbers of newly confirmed cases.

This data also suggests that Arizona's statewide lockdown policy from 1 April 2020 through 14 May 2020 was less than successful for the state. During the lockdown, hospitals and other medical facilities throughout Arizona operated well below their capacity, providing little benefit for the great economic cost of the closure of businesses and the resulting loss of jobs. Had the state instead limited these kinds of restrictive policies to more local levels of government within the state, allowing residents to live more regular lives as local conditions warranted, it might have avoided the rush that became a new coronavirus wave when the lockdown was lifted.

But then, that's true for many states which had previously avoided significant cases or deaths from the coronavirus. The good news is that because they learned from the worse mistakes made in the states that realized both high rates of cases and deaths, they will be much more likely to avoid having a similar magnitude of deaths. Without deaths to accompany the number of cases, their coronavirus experience will be much more like a seasonal influenza event, albeit a bad one.

25 June 2020 update: A closer look at COVID-19 deaths in Arizona.

References

The COVID Tracking Project. Coronavirus numbers by state. [Online Data, Multiple Formats]. Accessed 22 June 2020.

U.S. Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019 (NST-EST2019-02). [Excel Spreadsheet]. Last updated 30 December 2019. Accessed 14 March 2020.

Labels: coronavirus, data visualization

Coming into the third week of June 2020, we introduced two hypotheses for what caused the sharp, sudden, and now sustained deviation in the trajectory of the S&P 500 (Index: SPX), which rose on the week, but not by anywhere near enough to recover to its previous trajectory.

The two hypotheses for what caused the S&P 500 to plunge by 5.9% on Thursday, 11 June 2020 can be summarized as follows:

- The S&P 500 experienced a new Lévy Flight event, in which, investors suddenly shifted their forward looking focus from 2020-Q4, where it appears to have been since about 1 May 2020, to instead focus on the nearer term future of 2020-Q3.

- Investors adjusted their expectations for the future of the Federal Reserve's monetary policies, going from the anticipation of more expansionary policies to less expansionary ones.

Through the close of trading on Friday, 21 June 2020, we find the level of the S&P 500 is still consistent with what a dividend futures-based model would predict for both hypotheses, but that state of affairs will almost certainly change in the week ahead.

As shown in the alternative futures forecast chart above, the model anticipates the level of the S&P 500 will rise significantly in the week ahead to follow the trajectory associated with investors fixing their attention on the near-term future of 2020-Q3 if the Lévy Flight hypothesis holds, assuming they have not changed their expectations for how expansionary the Fed's monetary policies will be going forward following the end of its last meeting on 10 June 2020.But, if the shift that occurred on 11 June 2020 was the result of a change in expectations for the Fed's monetary policies, where the amplification factor in the dividend futures-based model suddenly changed to become less negative than it has been, we will see the trajectory of the S&P 500 start to consistently underrun the levels projected by the model as shown on the alternative futures chart above, which currently assumes no change in the amplification factor since 12 April 2020.

There's also the possibility that both things we've hypothesized could have happened, but here, we would still see the trajectory of the S&P 500 underrun the model's projections as currently shown on the chart above, which would allow us to reject the first hypothesis because of its assumption that there was no change in investor expectations for how expansionary the Fed's monetary policies will be.

With the stock market's behavior so interesting, this is definitely a fun time for us. Perhaps not as much fun as the first time we took advantage of a natural experiment with the S&P 500, but we're learning quite a lot in near real time!

- Monday, 15 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil prices rise 2% on optimism around OPEC+ output pact

- Fed launches long-awaited Main Street lending program

- Fed minions unleash more stimulus and share thoughts:

- Fed will begin purchasing corporate bonds on Tuesday

- Systemic racism slows economic growth: Dallas Fed chief Kaplan

- Fed's Daly says yield curve control could be 'little helper'

- Wall Street closes higher as Fed soothes recovery worries

- Tuesday, 16 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil prices rise 3% on signs of U.S. economic recovery

- U.S. economy starts long recovery as retail sales post record jump

- Bigger stimulus developing in the U.S. and Canada:

- Trump team prepares $1 trillion infrastructure plan to spur economy

- Fed corporate bond move relieves potential stigma for companies, say investors

- Bank of Canada focused on stimulus, low rates to support economy

- Fed minions consider coronavirus recession recovery path:

- Green shoots welcome but recovery still a long road, Fed's Powell says

- Instant View: Powell: No U.S. growth recovery until epidemic controlled

- Fed Chair Powell says strong job market can reduce U.S. racial inequality

- As 'ground zero' for crisis, Nevada shows need for fiscal aid: Fed's Powell

- Fed officials' GDP forecasts not likely factoring second COVID wave: Powell

- Fed has lots of 'dry powder,' Kaplan tells Bloomberg Radio

- Fed's Harker says he expects 'sharp recession' in 2020 with growth next year

- China says economy will grow in 2020, wants to buy up distressed U.S. businesses

- China's economy may grow 3% in 2020, government researcher says

- China keen to seek benefits from pandemic, distressed U.S. assets: report

- Wall Street closes higher on signs of economic recovery

- Wednesday, 17 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil slides on fresh COVID-19 outbreaks, bump in crude stocks

- Americans face new coronavirus challenge: a shortage of coins

- U.S. homebuilding rises moderately; jump in permits hints at green shoots

- U.S. mortgage rates hit record low, purchase applications at 11-year high

- Fed minions looking for a fiscal boost and consider coronavirus impacts

- Fed's Powell beats drum for more government aid to bolster economy

- Fed's Mester says rebound from likely record economic decline depends on containing coronavirus

- Fed's Bostic says pandemic exacerbated structural inequalities

- The world turned tospy turvy....

- Odds and ends for U.S. trade:

- China bought about $1 billion of U.S. cotton: Lighthizer

- U.S. trade chief vows to push for 'broad reset' at WTO

- Japan's exports fall most since 2009 as U.S. demand slumps

- S&P closes lower as new COVID-19 cases surge

- Thursday, 18 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil edges up on OPEC output cut compliance; pandemic still weighs

- U.S. retail foot traffic rebounds, more staff at work, as lockdowns ease

- McDonald's to hire 260,000 staff this summer as restaurants reopen

- Bigger trouble expected to continue in bellwether countries Switzerland, Taiwan:

- Swiss National Bank signals need to maintain negative rates

- Taiwan central bank holds fire on rates, cuts growth outlook again

- Bigger stimulus developing in U.S., but not so much in China:

- U.S. House Democrats unveil $1.5 trillion infrastructure plan

- China won't adopt 'flood-like' stimulus nor negative rates: regulator

- China pledges continued economic support but warns of liquidity hangover

- Fed minions share outlooks:

- Fed's Bullard says U.S. economy not out of the woods yet

- Fed's Mester says it could take two years for economy to return to pre-Covid levels

- Fed's Kaplan: Systemic racism is 'all of our problem' - MarketPlace

- S&P 500 closes nominally higher amid COVID-19 spikes, muted data

- Friday, 19 June 2020

- Daily signs and portents for the U.S. economy:

- Oil boosted by OPEC+ cuts even as virus weighs on market

- Running on 'hopium': Explaining the market rally in Wall Street's terms

- Trump renews threat to cut ties with Beijing, a day after high-level U.S.-China talks

- EU bosses seek greater power through stimulus in Eurozone:

- EU stimulus designed to support single market: executive chief

- EU parliament wants new EU taxes to finance recovery fund, EU budget

- EU leaders still split on recovery fund design, Commission says

- ECB's Lagarde urges quick EU recovery plan as economy in 'dramatic fall'

- Fed officials signal rising caution on U.S. economic recovery amid virus spread

- Fed's Clarida says there is more the central bank can do for U.S. economy

- Fed's Kashkari says U.S. economic recovery could take longer than hoped

- U.S. economy will likely need more support, Fed's Rosengren says

- How dismal has Japan's economy been for this state of affairs to be an improvement in its outlook?

- S&P 500 closes lower as COVID-19 resurgence casts a shadow on sentiment

Elsewhere, Barry Ritholtz presents a succinct summary of the positives and negatives he found in the week's markets and economy news.

Update 24 June 2020: It looks like we may be able to reject the first hypothesis. With the level of the S&P 500 clearly underrunning all of the dividend futures-based model's projections, as the index dropped 2.6% today to close at 3,050.33, it looks like we will be able to rule out this hypothesis because of its assumption that investors did not lower their expectations for how expansionary the Fed's monetary policies will be in the future.

Now the question is how much much of the change is Lévy Flight and how much is change in amplification factor? We'll need to develop two new hypothesis to sort out that question, but unlike this natural experiment, we suspect it will be much tougher to answer.

Here's a short introduction into the art of epicycles:

If you're curious to learn more, there's a 25-minute Mathologer video that explains epicycles, complex Fourier series and Homer Simpson's orbit, which is about as fun an entry point as you can have to the topic. But be warned, there will be math!

Labels: math, technology

Climate scientist Roy Spencer recently looked at atmospheric CO₂ concentration data and made a remarkable observation:

The Mauna Loa atmospheric CO2 concentration data continue to show no reduction in the rate of rise due to the recent global economic slowdown. This demonstrates how difficult it is to reduce global CO2 emissions without causing a major disruption to the global economy and exacerbation of poverty.

After removal of the strong seasonal cycle in Mauna Loa CO2 data, and a first order estimate of the CO2 influence of El Nino and La Nina activity (ENSO), the May 2020 update shows no indication of a reduction in the rate of rise in the last few months, when the reduction in economic activity should have shown up.

Since we've been using the same data to track the global economic impact of the coronavirus pandemic, that was surprising because we do see human fingerprints in the atmospheric CO₂ data, which we've indicated in the following chart:

Sharp-eyed readers will immediately recognize that we're not looking at the data the same way that Dr. Spencer is looking at it. He's looking at the overall concentration of carbon dioxide in the Earth's atmosphere over time, while we're looking at the trailing year average of the year over year change of those levels, where our data would correspond to his data that does not remove the contribution of ENSO (El Niño Southern Oscillation) activity.

In fact, if anyone would like to check our results, here's the data source. Using the data in the "Interpolated" column, calculate the year over year change for each month, then calculate the trailing twelve month average to address seasonality in the data. It should be pretty easy for anyone to replicate the heavy black line in our chart.

Our chart also indicates recessions and other events with negative economic impacts via the colored vertical bands, which are described at the bottom of the chart and which you can see are often correlated with declines in the rate at which carbon dioxide accumulates in the Earth's air. There are exceptions, which we believe may be attributed to unique economic stimulus efforts in recent years, but generally, changes in the pace at which CO₂ changes in the atmosphere does correspond to changes in human activities, typically rising during periods of global economic expansion and either failing to rise or falling during periods of global or widespread regional economic recession.

In terms of the overall level of carbon dioxide and its effect on the Earth's climate however, those changes are very small, which is why Dr. Spencer is correct to observe that the coronavirus recession is having very little effect on the total level of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere or the long-term trend for the climate, especially when compared to natural variations.

Still, it's cool that we can somewhat make out human fingerprints in the atmospheric CO₂ levels, where the following links will provide some background into our coverage of the subject.

Bonus Update: A Natural Experiment with Anthropogenic Climate Change

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: coronavirus, environment, recession

In 1800, 90% of the world's population lived in extreme poverty. In 2019, 10% did. During this 220 year span, 80% of the population of Earth rose out of extreme poverty. Which you can watch happen in the following short video animation of Gapminder's year-by-year global income distribution data.

Regions are grouped by color - red for Asia, blue for Africa, green for the Americas and yellow for Europe (which includes Russia). You can drill down to country-specific data using Gapminder's income mountain data visualization tool, where you can unstack the data to better follow a particular region, or just one country in particular.

We found some surprising results:

- Most of a country's shift out of extreme poverty begins coincides with its industrialization.

- The entire population of the U.S. has been effectively out of extreme poverty since about 1940.

- Most of China's population was stuck in extreme poverty through 1976, after which, the country suddenly began advancing out of it, slowly at first, then much more quickly, as if they had been unnaturally constrained before.

- India's rise out of poverty is also impressive, though it started progressing earlier than China and has maintained a somewhat slower pace.

- The largest country whose population still mostly falls below the extreme poverty line is the Democratic Republic of Congo, which though it has grown significantly in population, has fallen back behind other countries in its region in recent decades.

Of course, watching the short video we threw together is no substitute for playing with the income mountain tool, or any of the other fascinating tools available at Gapminder!

Labels: data visualization, income distribution

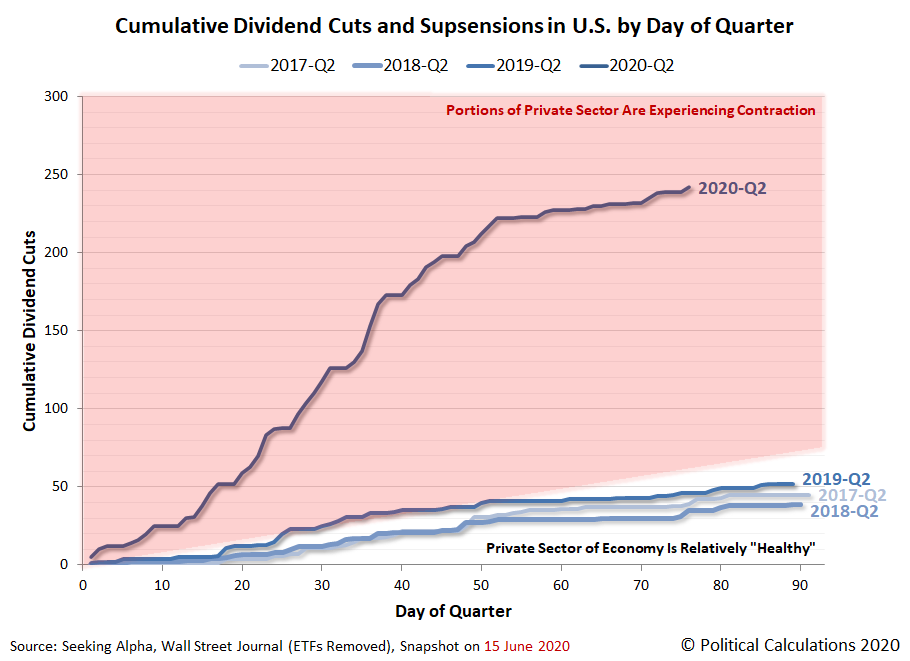

The number of dividend cuts being announced each day in the U.S. stock market began to explode in response to the developing coronavirus recession on 16 March 2020. Three months later, there are signs the worst may now be behind investors.

The best evidence of that change in affairs may be seen in the following chart tracking the cumulative number of dividend cuts and omissions announced during 2020-Q2, where from Day 62 through Day 76 (1 June 2020 through 15 June 2020), the rate at which these dividend reductions and suspensions are being announced has considerably slowed from the torrid pace we were observing earlier in the quarter.

So far in the first half of June 2020, we've counted 15 firms announcing dividend cuts or suspensions in our sampling of dividend declarations, far fewer than we've seen during similarly long blocks of time during the past three months. Here is the full list of U.S. firms either announcing dividend cuts or suspending their dividends from our regular sampling of dividend declarations during the first half of June 2020.

- Flexsteel Industries (NYSE: FLXS)

- A.H. Belo (NYSE: AHC)

- Oxford Square Capital (NASDAQ: OXSQ)

- Helmerich & Payne (NYSE: HP)

- Urstadt Biddle Properties (REIT-Retail) (NYSE: UBA)

- Annaly Capital Management (REIT-Mortgage) (NYSE: NLY)

- Chimera Investment (REIT-Mortgage) (NYSE: CIM)

- Dynex Capital (REIT-Mortgage) (NYSE: DX)

- The Children's Place (NASDAQ: PLCE)

- Monroe Capital (Mortgage) (NASDAQ: MRCC)

- Redwood Trust (REIT-Mortgage) (NYSE: RWT)

- Plymouth Industrial REIT (REIT-Industrial) (NYSE: PLYM)

- Independence Realty Trust (REIT-Residential) (NYSE: IRT)

- Permianville Royalty Trust (NYSE: PVL)

- Ready Capital (REIT-Mortgage) (NYSE: RC)

A quick review of the types of firms announcing dividend cuts and suspensions reveals that more than half are Real Estate Investment Trusts (REITs). Firms in the oil and gas industry and in the financial service industry tied to take second place at two each, with single firm entries in three other industry sectors to round out the list. Overall, the breadth of negatively impacted industries in the first half of June 2020 is also the smallest we've seen over similar periods of time during the last three months.

When the stock market is relatively healthy, we would expect to see 25 or fewer dividend cuts announced during the course of a single month. Since we're already more than halfway to that mark, we consider the number of dividend cuts being announced in the month to date to be elevated, though the number of dividend cutting firms is growing at a much slower pace than we've seen since mid-March 2020.

Is the worst now behind us for coronavirus recession-related dividend cuts?

About the Data

In the list of firms cutting or suspending dividends during the first half of June 2020 above, clicking the links for the publicly-traded company names will take you to our source for their dividend cut or suspension announcement. Clicking the ticker symbols will take you where you can find current price and other information related to the particular firm. Since our sources use automated systems to identify firms cutting or suspending their dividends, any errors in the list may be attributed to their methodology for detecting them. At some point, we'll discuss some of the more common errors we run into that arise from the automation in reporting, but that's still a discussion for a different day.

We also recognize the list includes a number of firms that pay variable dividends linked to their earnings and cash flows, which given the current market environment, is an irrelevant consideration that makes people who quibble over such trivia look incredibly foolish. In the current environment, the dividends for these firms are down because their operating environment has deteriorated since their last dividend distribution, just as it has for the firms that set their dividends independently of their earnings and cash flows who are also announcing dividend cuts and suspensions.

References

Seeking Alpha Market Currents Dividend News. [Online Database]. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Wall Street Journal. Dividend Declarations. [Online Database]. Accessed 15 June 2020.

Previously on Political Calculations

- 2020-Q1 Dividend Cuts Explode Into Contractionary Zone (24 March 2020)

- Dividends By The Numbers In March 2020 and 2020-Q1

- Dividend Cuts At The Midpoint of April 2020

- Pace of 2020-Q2 Dividend Cuts Accelerates (27 April 2020)

- Dividends by the Numbers in April 2020

- Dividend Cuts Continue Torrid Pace in First Half of May 2020

- Dividends by the Numbers in May 2020

- Is The Worst Behind Us For Coronavirus Recession Dividend Cuts?

Labels: dividends

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.