Calories are probably the last thing on your mind when you're drinking alcohol-containing beverages like beer, wine, distilled spirits or cocktails, but these kinds of drinks are far from being calorie-free.

The dietary information that you can typically get for these products will often list the number of calories per serving, but that serving size is often defined by a "standard drink", which in the United States, is 0.6 fluid ounces (14 grams) of "pure" alcohol, which doesn't necessarily match up with what a customary serving size may be.

For example, a customary size for a serving of beer is a pint (16 fluid ounces), where the standard size for a serving of beer is 12 fluid ounces. In this case, the standard size for beer often matches up with the size of containers in which beer can be purchased for home consumption, but will not if you order a beer at a public venue, such as a bar or tavern, where pints are commonly served, or at a stadium or ballpark, where serving sizes of up to 20-21 fluid ounces may be offered.

Similar issues arise for other types of alcohol-containing beverages, which is why we've put together the following dynamic table, which presents both the number of calories for a variety of "standard" alcohol-based drinks and also the number of calories in each per fluid ounce, which you can sort from either high-to-low or from low-to-high values by clicking on the column headings. If you're accessing this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click through to access a working version of the dynamic table.

| Calorie Content of Popular Alcohol-Containing Beverages |

|---|

| Beverage | Typical Calories per Serving | Typical Serving Size (ounces) | Average Calories per Ounce |

|---|---|---|---|

| Beer - Light | 103 | 12 | 8.6 |

| Beer - Regular | 153 | 12 | 12.8 |

| Cocktails - Bourbon and Water | 129 | 6 | 21.6 |

| Cocktails - Cosmopolitan | 146 | 2.75 | 53.1 |

| Cocktails - Daquiri | 112 | 2 | 56.0 |

| Cocktails - Gin and Tonic | 129 | 6 | 21.6 |

| Cocktails - Manhattan | 164 | 3.5 | 46.9 |

| Cocktails - Margarita | 168 | 4 | 42.0 |

| Cocktails - Martini (extra dry) | 139 | 2.25 | 61.8 |

| Cocktails - Martini (traditional) | 124 | 2.25 | 55.1 |

| Cocktails - Mojito | 143 | 6 | 23.8 |

| Cocktails - Piña Colada | 490 | 9 | 54.4 |

| Cocktails - Screwdriver | 199 | 7 | 28.5 |

| Cocktails - Whiskey Sour | 160 | 3.5 | 45.7 |

| Cocktails - Vodka and Tonic | 129 | 6 | 21.6 |

| Distilled Spirits - Brandy, Cognac | 98 | 1.5 | 65.3 |

| Distilled Spirits - Gin, Rum, Vodka, Whiskey, Tequila | 97 | 1.5 | 64.7 |

| Distilled Spirits - Liqueurs | 165 | 1.5 | 110.0 |

| Wine - Champagne | 84 | 4 | 21.0 |

| Wine - Port | 90 | 2 | 45.0 |

| Wine - Red | 125 | 5 | 25.0 |

| Wine - Sherry | 75 | 2 | 37.5 |

| Wine - Sweet | 165 | 3.5 | 47.1 |

| Wine - Vermouth (Dry) | 105 | 3 | 35.0 |

| Wine - Vermouth (Sweet) | 140 | 3 | 46.7 |

| Wine - White | 121 | 5 | 24.2 |

If you'd like to estimate the calories in a non-standard size alcohol-containing beverage, we could build a tool for you to do that math (and someday we might get around to taking on that project), but the U.S. government already has one. If you would like to see your tax dollars at work, go check it out!

As expected, the U.S. Federal Reserve acted to hike short term interest rates in the U.S. by a quarter percent, increasing its Federal Funds Rate to a new target range of 2.00% to 2.25%.

As it did, the risk that the U.S. economy will enter into a national recession at some time in the next twelve months stood at 1.6%, which is up by nearly half a percent since we last took a snapshot of this probability back in early August 2018. At present, that 1.6% probability works out to be about a 1-in-63 chance that a recession will eventually be found by the National Bureau of Economic Research to have begun at some point between 26 September 2018 and 26 September 2019.

That increase to a still very-low level is mainly attributable to the Fed's recent series of quarter point rate hikes, where its most recent was announced on 26 September 2018. Since last August, the U.S. Treasury yield curve has also slightly narrowed, as measured by the spread between the yields of the 10-Year and 3-Month constant maturity treasuries, which has also contributed to the increase in recession risk.

The Recession Probability Track shows where these two factors have set the probability of a recession starting in the U.S. during the next 12 months.

We continue to anticipate that the probability of recession will continue to rise through the end of 2018, since the Fed is expected to hike the Federal Funds Rate again in December 2018. As of the close of trading on Wednesday, 26 September 2018, the CME Group's Fedwatch Tool was indicating an 86% probability that the Fed will hike rates by a quarter percent to a target range of 2.25% to 2.50% at the end of the Fed's meeting on 19 December 2018. Looking forward to the Fed's 20 March 2019 meeting, the Fedwatch Tool is currently indicating a 53% probability that the Fed will not hike interest rates again before the end of the first quarter of 2019.

Conversely, there is a 47% chance it will hike interest rates by a quarter point at that time. With that kind of split in expectations, investors will have good reason to continue focusing on the Fed and its potential intentions for changing interest rates in 2019-Q1.

If you want to predict where the recession probability track is likely to head next, please take advantage of our recession odds reckoning tool, which like our Recession Probability Track chart, is also based on Jonathan Wright's 2006 paper describing a recession forecasting method using the level of the effective Federal Funds Rate and the spread between the yields of the 10-Year and 3-Month Constant Maturity U.S. Treasuries.

It's really easy. Plug in the most recent data available, or the data that would apply for a future scenario that you would like to consider, and compare the result you get in our tool with what we've shown in the most recent chart we've presented. The links below present each of the posts in the current series since we restarted it in June 2017.

Previously on Political Calculations

- The Return of the Recession Probability Track

- U.S. Recession Probability Low After Fed's July 2017 Meeting

- U.S. Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up After Fed Does Nothing

- Déjà Vu All Over Again for U.S. Recession Probability

- Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up as Fed Hikes

- U.S. Recession Risk Minimal (January 2018)

- U.S. Recession Probability Risk Still Minimal

- U.S. Recession Odds Tick Slightly Upward, Remain Very Low

- The Fed Meets, Nothing Happens, Recession Risk Stays Minimal

- Fed Raises Rates, Recession Risk to Rise in Response

- 1 in 91 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before August 2019

Labels: recession forecast

Dividend futures provide a lot of valuable information about what investors anticipate for their investments in the stock market. In a sense, they are the best available quantification of investor expectations for the future, where changes in their level are ultimately reflected in today's stock prices.

Consequently, we pay a lot of attention to dividend futures for the S&P 500, where we've found the CME Group's futures data for the S&P 500's Quarterly Dividends per Share and the S&P 500's Annual Dividends per Share to be a valuable resource.

We're writing today because we've reached an interesting point in 2018, where there's a discrepancy between the CME Group's quarterly dividend per share futures data and its annual dividends per share futures data for the S&P 500. The following chart illustrates what we're seeing in the data as of 21 September 2018, the expiration date [1] for the futures contract period covering the third quarter of 2018 (2018-Q3).

With the dividend futures contracts for the first three quarters having expired, the cumulative total of the S&P 500's dividends per share for 2018 to date is $39.90 per share, based on the values for these periods that we recorded on the day the dividend futures contracts associated with them expired. As of 24 September 2018, the CME Group's quarterly dividend futures is indicating that the S&P 500's dividend payout for 2018-Q4 will be $13.95 per share, which would bring the index' total dividends for 2018 up to $53.85 per share.

But, the CME Group's futures data for the S&P 500's annual dividends per share is projected to be $54.20 for 2018. With $39.90 of that total already on the books, that implies that the S&P 500's dividend payout for 2018-Q4 will be $14.30 per share, about 2.5% higher than what the CME Group's quarterly dividend futures for 2018-Q4 are indicating.

Granted, that's not a large amount, but the important thing to consider is that one of the these numbers is wrong. And when numbers tied to futures contracts like these are wrong, some sharp investor has an opportunity to make money. The question now is how should that sharp investor take advantage of the disparity between these two expectations for what the S&P 500's dividends per share will be in 2018-Q4?

Notes

[1] Dividend futures contracts run from the end of the third Friday of the month preceding the indicated period they cover through the third Friday of the month ending their indicated period of coverage, where they will indicate the amount of dividends expected to be paid out during this interval. For example, the dividend futures contract for 2018-Q1 ran from the end of Friday, 15 December 2017 through 16 March 2018, while the dividend futures contract for 2018 covers the period from the end of Friday, 15 December 2017 through 21 December 2018.

Labels: dividends, forecasting, investing, stock market

When we first visualized the long-term trends for American household spending through 2017, we couldn't help but notice how similar the trends were for the expenditures on Entertainment and on Health Insurance & Medical Expenses over much of that period, or really, from 1984 through 2008, after which, they diverged. The following chart zeroes in on the average annual expenditures that an estimated 130,001,000 American household "consumer units" spent on these two major categories from 1984 through 2017, where we've identified the primary contributing factor to that outcome.

In the next chart, we look at the same expenditures as a percentage of the total annual average expenditures of an American household consumer unit, this time, without the annotations identifying the Affordable Care Act as the primary contributor to the escalation in health care costs that caused the two household expenditures to diverge.

In the third chart, we drilled down into the subcategories of health care expenditures to break out the average amount that American household consumer units have spent on health insurance, medical services, medical supplies, and drugs to see how they've changed after 2008, which is when one or more of these expenses began to explode.

Wasn't the Affordable Care Act supposed to bend the cost curve for health insurance in the other direction?

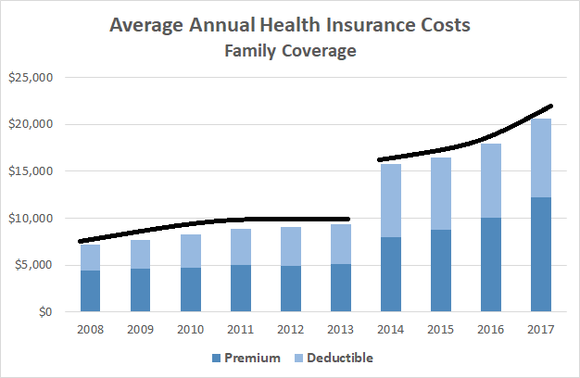

Clearly, that didn't happen, where we find the cost of health insurance has continued to grow at similar rates after spiking in 2014 with the 2013 implementation of the Affordable Care Act (while implemented in 2013, much of the increased cost associated with the ACA began to be incurred by U.S. households in 2014). Here's a neat chart that accompanied a September 2017 Motley Fool article showing what has happened to the average cost of health insurance coverage for American families from 2008 through 2017:

The important thing to recognize about all this data on the runaway cost of health insurance being paid by American households since the Affordable Care Act was signed into law and especially since it was implemented is that it is entirely attributable to actions taken by President Obama while in office for his signature domestic policy "achievement", which also encompassed the setting of health insurance 2017's premiums and deductibles, and also the Affordable Care Act's main enrollment period for that upcoming year.

If President Trump has done anything to influence health insurance costs, it hasn't shown up in any of this data yet. We'll have to wait to September 2019 when the results of the Consumer Expenditure Survey for 2018 become available to find out what that may be!

Data Sources

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau. Consumer Expenditure Survey. Multiyear Tables. [PDF Documents: 1984-1991, 1992-1999, 2000-2005, 2006-2012, 2013-2017]. Reference Directory: https://www.bls.gov/cex/csxmulti.htm. Accessed 11 September 2018.

Labels: health insurance, personal finance

The fourth week of September 2018 was fairly uneventful for the U.S. stock market. Mainly, that's attibutable to the pre-FOMC meeting media blackout that silences Fed officials, who had been making quite a bit of noise in previous weeks.

Still, it was a big week for the S&P 500 (Index: SPX), in that it reached a new record high closing value of 2,930.75 on Thursday, 20 September 2018. And while the S&P dipped slightly on Friday, coinciding with a pullback in tech stocks, the Dow Jones Industrial Average (Index: IND) went on to set its own new record high to close the week.

What makes the week that was really stand out from preceding weeks is how little news there was to drive stock prices during it, where investors appear to be focusing more strongly on the distant future quarter of 2019-Q1 in setting the level of the S&P 500, as suggested by our spaghetti forecast chart. The likely reason why is because investors are now giving a little over a 50% chance that the Fed will hike short term interest rates in the U.S. shortly before the end of that quarter, where investors will be looking toward the FOMC meeting this week for indications of what the Fed will do at that time.

Until that happens, we're afraid that we're all in for an extended and unsatisfyingly bad episode of "Will They Or Won't They?" in market-related news coverage this week. And then the calm before storm will end on Wednesday afternoon, after which, investors will switch to "Watch What Happens Next". Which should not ever be confused with a market-edition of Watch What Happens L!ve, although that might be more entertaining.

Speaking of calm before the storm, here's what an uneventful week looks like in terms of market-moving news headlines when the Fed's minions have been muffled....

- Monday, 17 September 2018

- Tuesday, 18 September 2018

- Wednesday, 19 September 2018

- Thursday, 20 September 2018

- Friday, 21 September 2018

Elsewhere, Barry Ritholtz listed the positives and negatives he identified from the week's news of the economy and markets.

Suppose, for an instant, that there's nothing unique about you, other than being an average American that has reached your current age. As such an average American, how much longer can you reasonably expect to live?

That isn't an idle question! While unique circumstances such as your heredity and your lifestyle choices certainly affect your odds of reaching a given age, where the government is concerned, you're just a statistic. A numeric blip around which things like future spending levels for Medicare and Social Security benefits are determined, where you are just a number to be managed. Managed, that is, until your personal lifespan countdown clock stops ticking.

How much time do the government's planners, who don't know you any better than we do, think you have left?

Answering that question is what our latest tool is all about! We extracted the latest remaining life expectancy data from the National Center for Health Statistics' United States Life Tables for 2014, which is the most recent data available. From that data, we constructed a mathematical model to represent the remaining life expectancy for all Americans given their current age. The following chart shows the model we created against the official remaining life expectancy data.

From here, if you want to estimate how much time you have remaining, assuming that you're an average American drawn from random among the total population, just enter your current age into the tool below. If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a working version of the tool on our site.

Because the life tables don't extend beyond Age 100, we've capped the maximum age to that level for our tool's results. If you enter a higher age, you'll get the results for Age 100. We've likewise set a minimum age of 0 for the tool as well.

If you'd like to get a better indication of how much time you, as an individual, might reasonably expect to live, we recommend the Living to 100 calculator, which allows you to factor in many of the unique factors that can significantly influence how long you'll actually live.

Previously on Political Calculations

- Will You Ever Be 100? - Well, will you? There's only one way to find out, and you will need to click through to do so!

- Estimating Your Age Like a Tree - Aren't sure how old you are? We have a tool for that!

- How Much Longer Can You Expect to Live? - Our original tool, built using the data from the 2004 U.S. life tables. If you want to see how life expectancy for your age has changed over the past decade, this is the tool for you....

Labels: demographics, health, tool

How has the taste of Americans for alcohol changed since the start of the 21st century?

We're going to answer that question today using excise tax collection data reported by the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau to the Internal Revenue Service from 2000 through 2017, which can give us an idea of how much beer, wine and distilled spirits Americans are consuming because the federal excise taxes that apply for these products are assessed by the gallon or barrel. Since the excise tax rates for these products have been stable since the beginning of the century, the amount of taxes per capita (or really, per American adult Age 21 or older) should be directly proportionate to the amount of each of these alcohol types that Americans have consumed in each year since 2000.

The following chart shows what we found in doing that math:

Overall, the amount of alcohol excise taxes collected per Age 21+ American has risen from $41.12 in 2000 to $44.89 in 2017, which suggests that the average adult American has increased their alcohol consumption by 9%. Within that consumption, there are clear rising trends for wine and especially for distilled spirits, which are displacing beer as a source of alcohol excise tax revenue for the U.S. government.

These trends can be seen more clearly in the following chart, where we show the relative share that each type of alcohol has contributed to federal excise tax collections from 2000 through 2017.

References

Political Calculations. U.S. Federal Alcohol Taxes in the 21st Century, 23 August 2018.

U.S. Internal Revenue Service. Federal Excise Taxes or Fees Reported to or Collected by the Internal Revenue Service, Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau, and Customs Service. 1999-2016. [Excel Spreadsheet]. Accessed 18 August 2018.

U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Intercensal Estimates of the Resident Population by Single Year of Age and Sex for States and the United States: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2010. [CSV Data]. 12 December 2016. Accessed 18 August 2018.

U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population by Sex, Single Year of Age, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2017. [Online Database]. 12 June 2018. Accessed 18 August 2018.

When it was first officially established on 3 March 1957, the S&P 500 (Index: SPX) had a total market capitalization of $172 billion. Over twenty five years later, at the end of 1982, the market capitalization of the entire S&P 500 had grown to more than $1 trillion.

Now, nearly 36 years later, at least two of the 505 companies that currently compose the index have market caps that have reached values of $1 trillion or more: Apple Computer (Nasdaq: AAPL) and Amazon (Nasdaq: AMZN), neither of which existed in 1957 and only one of which existed in 1982.

Overall, the market capitalization of the entire S&P 500 stands at roughly $25.8 trillion through the end of August 2018. The following chart tracks the history of the index' market valuation since it reached $1 trillion in value. We also have a chart showing the vertical axis on a logarithmic scale if you would prefer to see that version!

A third company, most popularly known as Google but officially called Alphabet (Nasdaq: Amazon (Nasdaq: GOOG and GOOGL), which also did not exist in either 1957 or in 1982, could also reach that lofty market valuation during 2018.

Labels: SP 500, stock market

We're going to have some fun exploring some of the trends in the average American household spending data contained within the 2017 Consumer Expenditure Survey (CEX), where we'll start with what Americans are paying to either own a home or to rent a residence in the United States.

The chart below shows all the historic data recorded for the amount that all American household "consumer units" have paid on average if they're buying a home, where they pay principal and interest on a mortgage, or if they are renting their dwelling from 1984 through 2017.

In this chart, you can see where the cost to buy a home in the U.S. rose rapidly before peaking in 2007, after which, the cost to own crashed until 2016, where it has recently started rising. Meanwhile, we can see that the cost to rent a dwelling has steadily increased without serious interruption from 1984 through 2017, where the rate at which American household expenditures for rent have grown at a faster pace since 2005 than they did in the 20 previous years.

It's important to note here that the data reported by the Consumer Expenditure Survey is spreading all these payments out over all household consumer units in the United States. In 2017, those 130,001,000 households include 48,231,000 that pay rent and 47,129,000 that have mortgages. The remaining 34,641,000 households own homes with no mortgages, and thus have $0 expenditures for either mortgage principal and interest payments or for rent.

We can do some back-of-the-envelope math to work out what the average rent payment or mortgage principal plus interest payment is for the Americans who have these payments. In the case of rent, we can start with 2017's $4,167 average annual expenditures on rented dwellings and multiply it by 130,001,000 households to get the aggregate amount of rent paid in the U.S. according to the 2017 CEX survey of $541,714,167,000. Dividing that amount by 48,231,000 renters gives us an annual average rent of $11,232. To get to the average monthly rental payment for the renters surveyed by the BLS and Census Bureau, we divide by 12 to find out that it is $935 per month.

That figure is lower than the "record-high average of $1,405 per month" rent figure that RentCafe estimated using data from Yardi Matrix covering apartments in cities with over 100,000 residents. The CEX data also covers smaller population centers, so it's reasonable that its reported rent figure would be less than that figure, but we should note that it is also likely a record high.

Looking at mortgage holders, the average principal paid in 2017 was $1,839 and the average mortgage interest and other charges paid was $3,265), which combined for an average mortgage payment of $5,104 for all 130,001,000 American household consumer units. Doing similar math to what we did for rent, we came up with an average monthly mortgage principal plus interest payment of $1,173 for Americans buying their homes, which is about 25% higher than the average monthly payment of American renters. Or if you prefer, in 2017, the average rent in the U.S. costs 80% of what the average payment to a mortgage lender is.

In doing this analysis, we're omitting other costs that are often included in mortgage payments, such as property taxes and homeowner's insurance. We may come back and revisit the topic at some point in the future, but since you've now seen how to do the math, if you want factor those expenditures into it, you're more than welcome to beat us to the punch!

As we close, we'll leave you with the immortal wisdom of Jimmy McMillan, who back in 2010, represented New York's The Rent Is Too Damn High Party in that state's election for governor.

In 2018, he would be a much better governor for New York than any of the current candidates!

References

Szekely, Balazs. National Apartment Rents Hit New Milestone, Demand for Small Apartments Catches Up with Family-Sized Rentals. RentCafe Blog. [Online Article]. 4 July 2018.

Lane, Rachel. U.S. housing rents hit record-high average of $1,405 per month. MoneyWatch. [Online Article]. 6 July 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau. Consumer Expenditure Survey. Multiyear Tables. [PDF Documents: 1984-1991, 1992-1999, 2000-2005, 2006-2012, 2013-2017]. Reference Directory: https://www.bls.gov/cex/csxmulti.htm. Accessed 11 September 2018.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics and U.S. Census Bureau. Consumer Expenditure Survey. Table 1702. Housing tenure and type of area. [PDF Document]. Accessed 11 September 2018.

Labels: data visualization, math, personal finance, real estate

The S&P 500 closed out the third week of September 2018 on an upnote, but not by so much that it resumed setting the kind of new record highs that it was just a few weeks ago.

The following chart shows the latest update to our spaghetti forecast chart for the trajectory of the S&P 500, where we find that investors would appear to be currently splitting their forward-looking attention between the future quarters of 2018-Q4 and 2019-Q1, with a somewhat heavier focus on 2019-Q1.

As for why investors would appear to be looking at these two future quarters in particular, we suspect that it has a lot to do with the Federal Reserve's plans for changing its Federal Funds Rate (FFR), the interest rate that banks pay for borrowing money from the Fed, which sets the floor for short term interest rates in the United States. When we last reported upon investor expectations for the future for the FFR just over a month ago, investors were anticipating that the Fed would hike that rate by a quarter point twice more in 2018, in both September and December, then take a breather until June 2019 before doing it again.

Since then, the combination of reports of continued strength in the U.S. economy with multiple statements by the Fed's minions in recent weeks is giving investors reason to anticipate that there will be no breather in the Fed's latest series of short term interest rate hikes. The following table indicates what the CME Group's FedWatch tool anticipates for the future of the Federal Funds Rate based on information from the FFR futures market. (Please click here to view a screen shot of the table if you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, but which doesn't properly render the table.)

| Probabilities for Target Federal Funds Rate at Selected Upcoming Fed Meeting Dates (CME FedWatch on 14 September 2018) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOMC Meeting Date | Current | ||||||

| 175-200 bps | 200-225 bps | 225-250 bps | 250-275 bps | 275-300 bps | 325-350 bps | 350-375 bps | |

| 26-Sep-2018 (2018-Q3) | 0.0% | 97.4% | 2.6% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 19-Dec-2018 (2018-Q4) | 0.0% | 20.0% | 77.0% | 3.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| 20-Mar-2019 (2019-Q1) | 0.0% | 8.0% | 41.9% | 45.0% | 5.0% | 0.1% | 0.0% |

The table confirms that investors are now anticipating quarter point rate hikes in September 2018 and December 2018. In addition, as of the last week, investors are now also given just over a 50% probability that the Fed will again hike interest rates by another quarter point or more in March 2019 (as can be determined by adding the probabilities in the table cells highlighted in yellow for the Fed's March 2019 meeting).

That assessment isn't just based on this data. It's also based in part from the news reports we reviewed during the third week of September 2018, where the following stories appeared noteworthy in describing the noise in the market.

- Monday, 10 September 2018

- Tuesday, 11 September 2018

- Wednesday, 12 September 2018

- Brent reaches $80 a barrel after fall in U.S. crude stocks

- Trump 'definitely' boosted U.S. growth, Fed's Bullard says

- Fed has room to raise interest rates for some time, Brainard says

- Fed says it whipped U.S. unemployment, maybe too well

- Dow, S&P 500 end up slightly after trade talk news; Apple slips

- Thursday, 13 September 2018

- Friday, 14 September 2018

- Oil mixed as China tariff talk scotches early rally

- Trump readies tariffs on $200 billion more Chinese goods despite talks: source

- Fed policy to turn mildly restrictive in 2019, Evans says

- Fed's Evans says premature to read much into yield curve

- Fed's Evans sees one or two more rate hikes this year

- Yellen: Fed should commit to future 'booms' to make up for major busts

- Wall Street flat as looming tariffs offset gains in financials

For additional aspects of the week's economics and markets-related news, be sure to check out Barry Ritholtz' list of the positives and negatives he found in the week's data.

How much of a health benefit can you get for the public by imposing taxes on products like sugary soft drinks?

Advocates for soda taxes frequently cite positive health benefits as the reason for why governments should impose this kind of sin tax on the distribution and sale of sugary beverages to consumers within their jurisdictions. In doing so, many claim that such a tax would fix what in economics is called a "negative externality", which in this case, represents higher costs to public health systems for treating conditions such as obesity and diabetes, where sweetened beverages are targeted by soda tax advocates for their contributions to the problems they proclaim because of their popularity and their sugary calorie content.

But for such an argument to be valid, the imposed tax would have to realistically achieve its desired aims without any unintended consequences that create new costs or other problems that offset any of the realized benefits. Since soda taxes have only been applied in a limited number of jurisdictions in recent years, the data available to assess their impact is relatively limited, so many of these advocates' claims of achievable health benefits have not been able to be challenged.

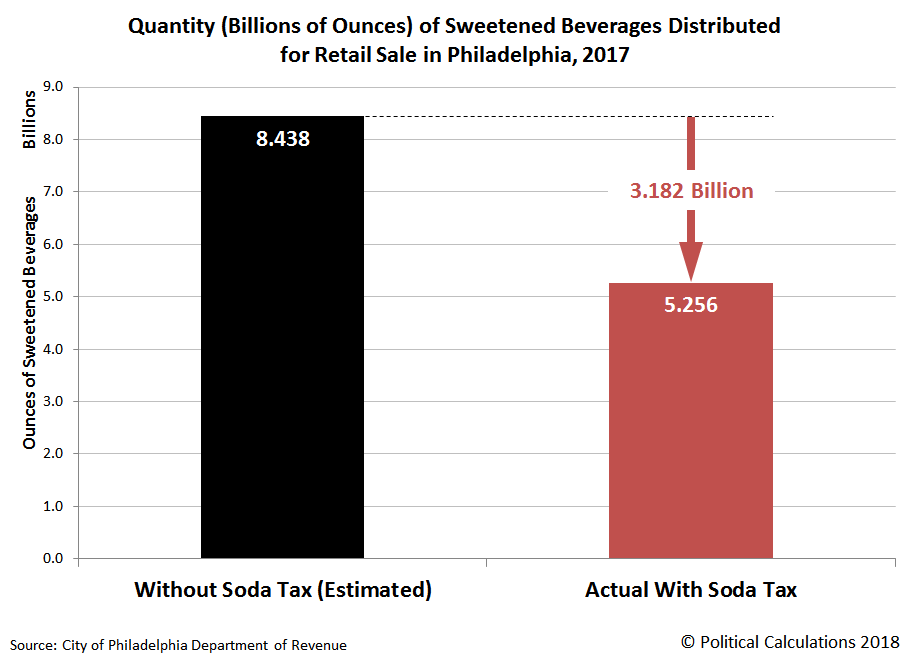

We do however have evidence from what happened in Philadelphia during the first year of that city's experience with its controversial 1.5-cent-per-ounce soda tax, which it calls the "Philadelphia Beverage Tax". Using monthly tax collection data compiled by the Philadelphia Department of Revenue, and the city's expectation for what would be its annual revenue from the tax and its predicted reduction in sweetened beverage sales, we are able to identify the amount of soda that was distributed for sale in Philadelphia in 2017 and also how much city officials believe would have been distributed in the absence of its soda tax. The following chart shows those results.

In the next chart, we've simply tallied up the monthly data for the number of ounces of sweetened beverages subject to the Philadelphia Beverage Tax to get the picture for the quantity of beverages that would have been distributed for sale in the city without the tax and also the amount of what was actually distributed in the city after the tax was imposed on 1 January 2017.

In this second chart, we see that the Philadelphia Beverage Tax reduced the amount of diet and regular sweetened beverages in the city by the equivalent of 3.182 billion ounces in 2017, which is quite a lot, but should be expected to happen whenever a tax imposed by a government causes the price of a product that consumers buy to increase substantially. From here, we'll need to do some math to estimate how much that works out to be in potential calorie reduction.

So we built a tool to do that math! The following tool will estimate the reduction in consumed calories from the implementation of the Philadelphia Beverage Tax on a per capita basis, where we've added a factor to account for the share of non-diet "regular" beverages that are consumed each year, since these are where the vast bulk of the sugary calories are to be found. If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a working version of this tool. If you would rather not click through, you can view a screenshot of the tool's results with the default data.

Using the default data in our tool, we find that the reduction in the amount of sweetened beverages distributed in Philadelphia would have been sufficient to reduce the weight of every man, woman and child in the city by five pounds, assuming that none of these people increased their consumption of other calorie containing beverages and foods, and also assuming that they didn't leave the city to buy sweetened beverages that were not subjected to the city's controversial soda tax, or acquired them from bootleggers who smuggled them in.

We've already run the numbers for the increased calories of alcohol-based beverages sold within the city, whose sales surged during 2017, which totaled the equivalent of an additional 114 12-ounce containers of beer consumed by each Philadelphian over the year. Assuming 149 calories per container per person, the average Philadelphian consumed an additional 16,986 calories during 2017. With 3,500 calories corresponding to the gain or loss of a pound of body weight, that increased alcohol consumption would, when spread over every man, woman and child in the city, put an average of 4.9 pounds back onto the bodies of every Philadelphian! [In reality, a larger amount of weight would be gained by the legal drinking age portion of the city's population, but you get the idea....]

When you consider that we haven't yet accounted for sweetened beverage consumers shifting their shopping to outside the city to avoid the Philadelphia Beverage Tax, or the smuggling of untaxed soda into the city for sale by bootleggers, it's pretty clear that Philadelphia's soda tax failed as meaningful health improvement measure for the city's population, where the average calorie consumption per capita almost certainly was either flat or rising during 2017.

One detailed marketing study found that sales of sweetened beverages increased by anywhere from 5% to 38% depending on beverage type in Philadelphia's suburbs during the first five months the tax was in effect, but we don't know the net extent to which this increased sales volume of sweetened beverages not subject to Philadelphia's soda tax offset reduced sales in the city for the full year. In our tool, we initially set the default value of the tax avoidance factor to 0%, but we believe a conservative estimate would fall between 10% and 20% - you're more than welcome to substitute these percentages or your own estimate into our tool to take this particular factor more realistically into account.

Update 12 October 2018: 10-20% proved to be a very conservative estimate - based on new information that was published after this article, the actual share may be in the ballpark of 59%-79%, where we would again seek to err toward the low side of the estimate.

Other factors that we're not considering is the extent to which reduced soft drink consumption may have offset by purchases of bottled water and untaxed packets of sweetened drink powders, where consumers could blend their own calorie-rich sugary beverage. Likewise, we're also not considering whether consumers in the city, instead of buying taxed soda pop, instead opted to increase their consumption of any of the many inexpensive, calorie-laden treats that are exempt from Philadelphia's soda tax to satisfy their sweet tooth.

Since reduced calorie consumption would have provided the primary health benefit of having imposed such a tax, the absence of any significant reduction would mean that no positive benefits through reduced medical costs for the treatment of excessive calorie consumption-related health conditions were realized on average among Philadelphia's population as a result of the city's soda tax. But then, since the Philadelphia Beverage Tax was never intended to improve the health of Philadelphians, this outcome should not be a surprise.

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.