The Antikythera Mechanism is one of the earliest, most complex computers ever devised. Built over 2,100 years ago and recovered from an underwater Roman shipwreck a little over a century ago, this ancient clockwork bronze didn't yield its secrets until the early 2000s, when a cutting edge 3-D X-ray tomography machine the size of a van was transported to Athens to scan the device, which itself could fit in a small box.

PBS' Nova 2012 documentary featured what the X-ray analysis found. We've embedded the full 46-minute documentary below, but we've set it to start at the 16:07 mark, where the first five minutes from this point of the video reveals the researchers' major discoveries about what the device was designed to do and how it worked.

The rest of the documentary is fascinating, where the researchers found astronomical calculations lurking within the gears of the device, which was used to model the cosmos as the Greeks knew it and to predict future events, such as solar eclipses.

Since we're on the cusp of a holiday weekend, we'll share a much shorter video (it's only a minute long) that's somewhat connected, in which the rotation of the Earth over a three hour period is revealed against an unmoving celestial background fixed on the Milky Way:

Previously on Political Calculations

Labels: technology

Fueled by falling new home prices and falling mortgage rates, the U.S. new home market is experiencing a rebound in its fortunes.

Starting with falling new home sale prices, preliminary and revised data reported by the U.S. Census Bureau for July 2019 shows that the average and median sale prices of new homes sold in the United States have continued a downward trend into mid-2019.

Focusing on median new home sale prices, the next chart presents the trailing twelve month average of these prices to smooth out month-to-month volatility in the data to identify trends since July 2012, which marked the beginning of a prolonged surge in median new home prices.

There have been three major trends during that time, each characterized by a relatively steady rate at which median new home sale prices rose, but with the rate of increase declining in each phase. The last upward trend saw prices escalate at an average rate of $930 per month from September 2015 to October 2018, after which the trend broke down and new home sale prices began falling instead. Had this last trend continued, we estimate that trailing year average of median new home sale prices of $318,483 shown in the chart above would be about $20,000 higher.

But that trend didn't continue, with median new home sale prices falling sharply as the median household income in the U.S. has risen, which has combined to make new homes in the U.S. the most relatively affordable they have been since August 2013. We can see that in the following chart showing the ratio of the trailing twelve month averages of median new home sale prices and median household income, where the median new home in the U.S. has dropped to be five times the median household income.

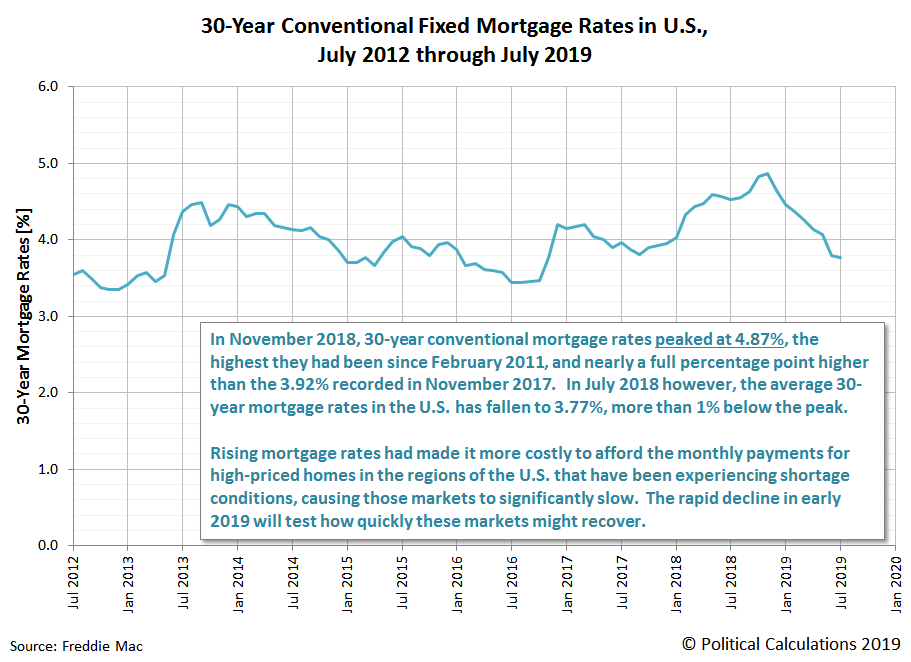

But it's not just home prices that have been falling in the U.S. Mortgage rates have also been falling since they peaked at 4.87% in November 2018, where at 3.77% in July 2019, they are now more than a full percentage point lower than they were at that time. The following chart shows the evolution of 30-year conventional mortgage rates from July 2012 through July 2019:

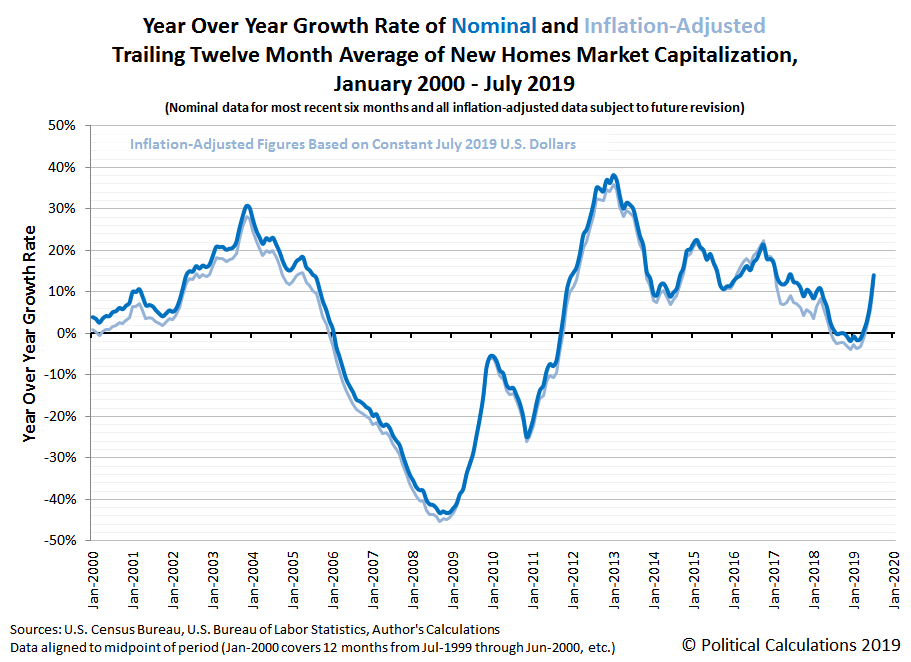

The combination of falling prices and falling mortgage rates means that new homes have become considerably more affordable than they were at the end of 2018. New home buyers are responding to the stimulative effect of these changes, with the number of sales increasing dramatically in recent months. The following chart presents our estimate of the market capitalization of the new home market in the U.S., where we've multiplied the average sale price of new homes sold in the U.S. by the number of new homes sold.

In nominal terms, the preliminary estimate of the trailing year average market capitalization of new home sales in the U.S. is the highest it has been since March 2007. That there has been a sharp uptick in the U.S. new home market capitalization is confirmed by examining the trajectory of its year over year growth rate.

This latter chart also reveals that the U.S. new home industry's market cap was effectively shrinking between July 2018 and April 2019, which was becoming a drag on the U.S. economy. That situation has only recently reversed in the months since.

The question now becomes what will it take for that momentum to be sustained?

Labels: real estate

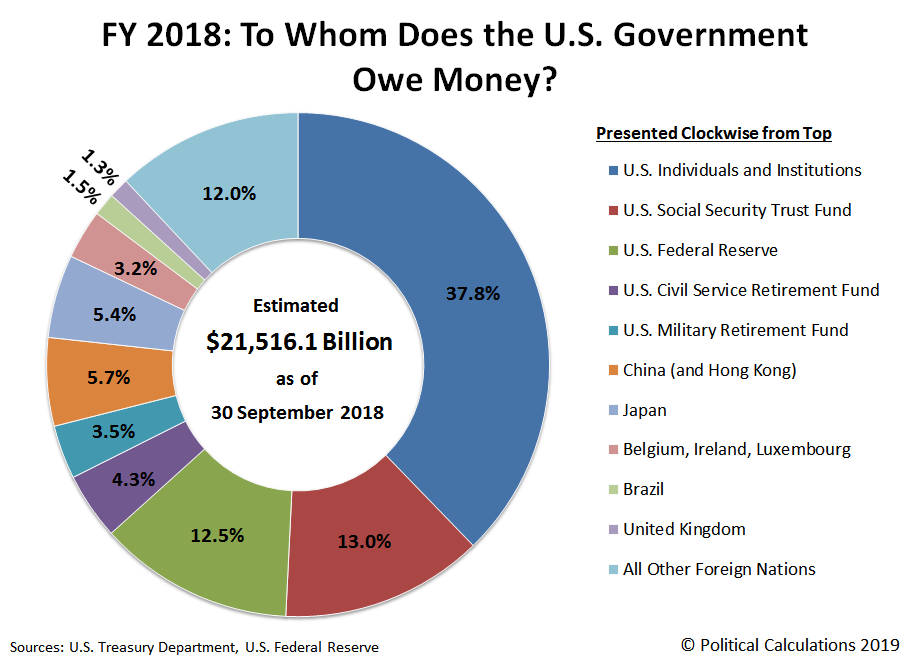

Who loans money to the U.S. government?

We've developed the following chart to answer that question, which is a companion to the 'donut' national debt ownership chart we've featured in the latest update to our "To Whom Does the U.S. Government Owe Money?" series.

For this chart, we've used a bar chart format to present the actual amounts owed to the U.S. government's major creditors, where we've also simplified the foreign-held portion of the data by splitting it up according to the type of creditor rather than by country.

In doing that, we find that private institutions (such as banks, insurance companies, mutual funds, etc.) and individuals make up the single largest category of lenders to the U.S. government with a combined total of $9,053 billion owed to U.S. and foreign holders of U.S. government-issued debt securities, such as Treasury bonds, short term debt, and federal agency bonds. Combined, these lenders own 42% of the $21,516 billion U.S. national debt recorded at the end of September 2018.

The second largest category is central banks, which for the U.S. means the Federal Reserve, and for the foreign category, refers to "foreign official" institutions. Together, the world's central banks account for $6,708 billion of all money owed by the U.S. government to its creditors, or 31% of the total public debt outstanding, with the Federal Reserve accounting for 12.5% of that amount.

The remaining categories we've broken out are covered by the U.S. government's "intragovernmental holdings" of the U.S. national debt, which includes the trust funds for Social Security and for Federal Hospital Insurance, as well as federal government operated pension funds for its civil service and military employees. These make up the "Big 4" holders of the U.S. national debt within the U.S. government, and with all other U.S. government holdings as of the end of the 2018 fiscal year, add up to $5,755 billion.

This latter category has begun to shrink because Social Security is now running an operating deficit, taking in less money than it spends, which means it has to cash in the U.S. debt securities it holds to make up the difference for paying out retirement pension benefits at promised levels to retired Americans.

References

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Treasury International Capital (TIC) System. Securities (B): Portfolio Holdings of U.S. and Foreign Securities. [Data Resources]. Accessed 27 August 2019.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Treasury International Capital (TIC) System. Monthly Holdings of U.S. Long-term Securities at Current Market Value by Foreign Residents. [CSV Data]. June 2019.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Debt to the Penny. [Online Application]. 28 September 2018.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Treasury International Capital (TIC) System. Historical Liabilities to Foreigners by Type and Holder. Short-term securities. Historical Data. [CSV Data]. June 2019.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. Final Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government for Fiscal Year 2018 Through September 30, 2018, and Other Periods. [PDF Document]. 12 October 2019.

Labels: data visualization, national debt

Compared to the first two quarters of 2019, Political Calculations' near real-time sampling of dividend declarations from data published by Seeking Alpha and the Wall Street Journal is showing considerably fewer dividend cut announcements.

The following chart shows where things stand nearly two-thirds of the way through the quarter to date:

Through Monday, 26 August 2019, we've counted a cumulative total of 26 dividend cut announcements during 2019-Q3, which compares with 40 and 41 having been announced at a similar point of time of during the earlier quarters of 2019-Q1 and 2019-Q2.

The following list of 14 U.S. firms that have cut dividends during the quarter to date includes only those that pay variable dividends from one period to the next, often as a straight percentage of their earnings.

- Sabine Royalty Trust (NYSE: SBR)

- Mesabi Trust (NYSE: MSB)

- Mesa Royalty Trust (NYSE: MTR)

- PermRock Royalty Trust (NYSE: PRT)

- Cross Timbers Royalty Tr (NYSE: CRT)

- Permianville Royalty Trust (NYSE: PVL)

- Pacific Coast Oil Trust (NYSE: ROYT)

- SandRidge Mississippian Trust II (NYSE: SDR)

- Nordic American Tankers (NYSE: NAT)

- Sturm Ruger (NYSE: RGR)

- ECA Marcellus Trust I (NYSE: ECT)

- Mesa Royalty Trust (NYSE: MTR)

- Permian Basin Royalty Trust (NYSE: PBT)

- Permianville Royalty Trust (NYSE: PVL)

All but two of these firms hail from the oil and gas producing sector of the U.S. economy, which went through a rough patch with falling oil prices in recent months (late April to mid-June 2019), which will translate into dividend cuts for these firms in subsequent months. Oil prices have risen more recently thanks to geopolitical tensions, where absent a major shock, we should see the number of these firms announcing dividend cuts either hold relatively flat or decline in upcoming months.

A bigger source of concern for investors are firms whose corporate boards set their cash dividend payouts to their shareholding owners independently of their revenues and earnings, where we have counted 12 in our 2019-Q3 sample to date, which we've listed below.

- Armour Residential REIT (NYSE: ARR)

- Columbia Banking System (NYSE: COLB)

- BlackRock Capital Investment (NASDAQ: BKCC)

- Och-Ziff Capital Management (NYSE: OZM)

- Falcon Minerals (NASDAQ: FLMN)

- AG Mortgage Investment Trust (REIT) (NYSE: MITT)

- Kingstone (NASDAQ: KINS)

- Entercom Communications (NYSE: ETM)

- Portman Ridge Finance (NYSE: PTMN)

- Dynex Capital (NYSE: DX)

- Briggs & Stratton (NYSE: BGG)

- Riverview Financial (OTCQX: RIVE)

Nine of these twelve firms belong to the financial sector of the U.S. economy, in which we include Real Estate Investment Trusts. This sector of the U.S. economy has experienced distress related to the Fed's series of interest rate hikes and its quantitative tightening policies, which they only just began to reverse at the end of July 2019.

The remaining three firms that fall in this category all come from different sectors of the U.S. economy and includes representatives from the media, insurance, and manufacturing industries.

Overall, we find the near-real time sample of dividend cuts to be consistent with the U.S. economy being relatively healthy at this point, though that may change as geopolitically motivated distress from the developing global economic slowdown works its way westward around the Earth from their points of concentration in the far east. Industrial sectors to pay attention to in upcoming quarters may add the agriculture, automotive, aerospace, and manufacturing sectors to the list of firms from the oil & gas and financial sectors of the U.S. economy experiencing the kind of distress that can lead to dividend cuts.

Labels: dividends

Friday, 23 August 2019 saw some of the most interesting investor reactions to new information that we've seen this year. The day started with China's announcement it would impose larger tariffs on U.S. goods, which sent stock prices lower. Then, Federal Reserve chair Jerome Powell spoke at the Fed's annual retreat at Jackson Hole Wyoming, where he gave the impression the Fed saw the U.S. economy as being strong enough where investors shouldn't expect much in the way of more rate cuts in the weeks ahead, which caused stock prices to rebound somewhat, up to where they were close to flat on the day.

And then, President Donald Trump reacted to both of these events, where suddenly, investors were forced to consider the possibility that the Fed could be compelled to cut interest rates in the U.S. more dramatically before the end of 2019 to address the fallout from escalations in the U.S.-China trade war.

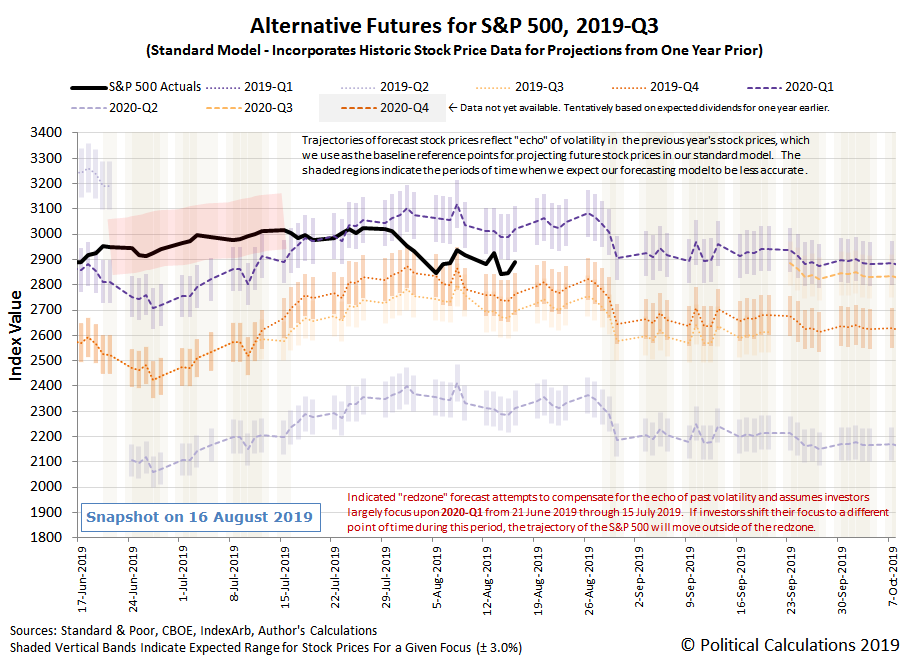

These dynamics compelled investors to shift their forward-looking attention from being split between 2019-Q4 and 2020-Q1 to instead be more tightly focused on 2019-Q4, sending stock prices significantly lower, with the S&P 500 (Index: SPX) closing the day down by 2.6%.

But that was last week. Looking ahead, we find that the short term echo of the stock market volatility that kicked up a month earlier should start affecting the accuracy of our dividend futures-based forecasting model by the end of the week ahead, similar to what we last observed in December 2018.

Now, as then, the volatility we're observing in stock prices is being principally driven by investors resetting their forward-looking time horizon from one point of time to others. In December 2018, the timing of those shifts proved to be very difficult to anticipate, where the random onset of new information directly drove those changes.

We anticipate the current market environment will be similarly chaotic in the weeks ahead, where we are curious to assess how well our 'standard' model might predict the future for stock prices without adjustment to compensate for the echo effect (as we do when we present redzone forecasts), where we'll be testing different techniques to compensate for the short term echo in our model's projections behind the scenes.

Meanwhile, to see what we mean for how new information causes investors to change how far forward in time they're looking in making their current day investment decisions, here are the major market-moving headlines we sampled from the past week.

- Monday, 19 August 2019

- Oil rises 2% after attack on Saudi field, stimulus expectations

- Bigger trouble developing in China all over:

- German economy could continue to shrink: Bundesbank

- Japan's exports slip for eighth month, sales to China drop as recession fears grow

- Faced with global downturn fears, Japan Inc avoids raising bonuses: Reuters poll

- Bigger stimulus developing in China:

- Trump says Fed should cut interest rates by one percentage point

- Wall Street rallies on hopes of global economic stimulus

- Tuesday, 20 August 2019

- Oil steadies as hopes of easing trade tensions lend support

- Bigger trouble developing in China all over:

- Latin America lacks ammunition to fight global economic slowdown

- U.S. Steel plans to lay off hundreds of workers in Michigan

- Bigger stimulus developing in China all over:

- China trims lending rates with new benchmark, more cuts expected

- Italy needs 50 billion euro budget for 'shock' stimulus: Salvini

- Trump looking at possible U.S. payroll, capital gains tax cuts

- Wall Street rally ends as financial shares slide

- Wednesday, 21 August 2019

- Oil steadies as U.S. crude stocks draw but fuel inventories rise

- Bigger trouble developing all over:

- Dropping global bond yields, recession fears put BOJ in a bind

- Exclusive: China's Tianjin government orders Bohai Steel restructuring start by September: sources

- Fed was divided on rate cut, wanted to avoid appearing on path for more cuts

- Instant View: July FOMC minutes - 25 basis points cut seen as a mid-cycle adjustment

- Trump heaps pressure on Fed and its chairman Powell to cut rates

- Fed's Kashkari says U.S. central bank should use forward guidance now: FT

- Stocks rise with focus on stimulus; U.S. yield curve briefly inverts

- Thursday, 22 August 2019

- Oil eases as Fed's Jackson Hole meeting gets underway

- U.S. 30-year, 15-year mortgage rates fall to lowest since Nov 2016: Freddie Mac

- U.S. factory sector contracts for first time in a decade: IHS Markit

- Fed's Powell, under pressure, likely to stick to 'mid-cycle' message

- Two Fed officials see no case for rate cut now; Kaplan 'open-minded'

- Fed's George says does not yet see signal of downturn in economy: CNBC

- Fed's George says she would be happy to keep rates at current levels

- S&P 500 stalls in economic data offset, ahead of Fed chair's speech

- Friday, 23 August 2019

- Oil prices slide as U.S.-China trade war escalates

- U.S. new home sales drop sharply, point to more housing weakness

- Something less than "whatever it takes" for stimulus in a weakening Eurozone economy:

- ECB's Weidmann sees no need for economic stimulus: newspaper

- Fed's Clarida says global economy has worsened since July: CNBC

- UK economy headed for stagnation in third quarter: BoE's Carney

- Something less than "whatever it takes" for stimulus from the Fed in a weakening U.S. economy:

- Powell: Fed to act as appropriate to keep expansion going

- Fed's Mester says approaching Fed's next policy meeting with open mind: CNBC

- Fed's Bullard says a 'robust debate' is coming over steep rate cut

- Trump asks who is bigger enemy, Fed Chair Powell or China's Xi?

- Fed's Kaplan: trade, immigration affecting U.S. economy, not monetary policy

- U.S.-China trade war heats up:

- China strikes back at U.S. with new tariffs on $75 billion in goods

- Trump's China trade comments send US stocks tumbling

- Dow plummets more than 600 points after Trump orders US manufacturers to leave China

For a week that was as unbalanced as the third week of August 2019 was, Barry Ritholtz has a remarkably balanced list of 5 positives and 5 negatives he found in the week's economics and market-related news. Do check it out to get a bigger picture of what was in the week's news than the headlines we highlighted above.

Imagine an old fashioned weather vane, one that has an arrow that points in the direction the wind is blowing that pivots about a point in the middle of the arrow.

Now watch the following video, which involves a mathematically sculpted, 3D-printed design by Kokichi Sugihara to execute a pretty cool optical illusion.

HT: Mark Perry.

Labels: math, technology

A quote from Charles Dickens' A Tale of Two Cities seems an appropriate introduction:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to heaven, we were all going direct the other way - in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Let's start with an update to the Recession Probability Track, which is based on Jonathan Wright's 2006 paper describing a recession forecasting method using the level of the effective Federal Funds Rate and the spread between the yields of the 10-Year and 3-Month Constant Maturity U.S. Treasuries, where we will see the early effects of both the Fed's quarter point rate cut that was announced on 31 July 2019 and the recent inversions of the U.S. Treasury yield curve, which has seen long term rates fall below short term rates.

Using Wright's recession forecast model, with an average Federal Funds Rate of 2.33%, an average 10-Year constant maturity Treasury yield of 2.01%, and an average 3-Month constant maturity Treasury yield of 2.16% over the last 91 days, we find the probability that a recession will eventually be found to have begun between 21 August 2019 and 21 August 2020 is 11%, or rather, a 1-in-9 chance of a recession starting before September 2020.

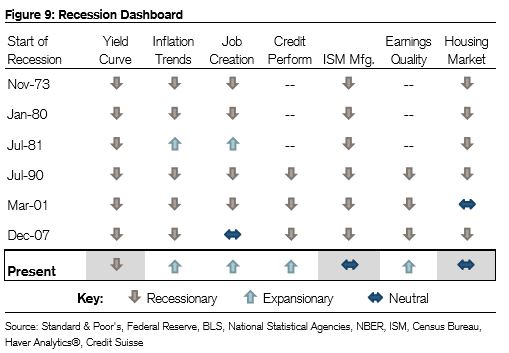

That's the 'best of times' outcome, which would appear to be backed by the sunny outlook indicated by Credit Suisse's latest update to its U.S. recession dashboard:

Economic data looks nothing like that of a recession, according to Credit Suisse.

The firm created a “recession dashboard” in which the firm tracked the state of seven main economic indicators at the start of each recession dating back to 1973. In past recessions, most of the indicators were “recessionary” or “neutral,” while the current state of the economy is telling a different story.

“Key signals such as labor and credit trends remain quite healthy,” said Credit Suisse’s chief U.S. equity strategist, Jonathan Golub, in a note to clients Tuesday.

But there's potentially a problem here for assessing the probability of a future recession in today's economic environment. Because Wright's model was developed using historic data from before the Great Recession, it doesn't consider factors like quantitative easing or quantitative tightening in its assessment, which can achieve effects similar to what would happen if the Fed either hiked or cut U.S. interest rates, without changing the level of the Federal Funds Rate itself.

When the Fed implemented its various quantitative easing monetary policies from 2009 through 2015, this effect was measured as the "shadow Federal Funds Rate", which became the primary means by which the Fed sought to stimulate the U.S. economy after it cut the Federal Funds Rate all the way to a near-zero level. By May 2014, these policies delivered the equivalent of an additional three percentage point reduction in the Federal Funds Rate while it was nominally held between 0% and 0.25%.

After May 2014, the Fed reversed this stimulative policy, which might be called quantitative tightening. Several analysts have indicated they believe quantitative tightening added the equivalent of three full percentage points to the nominal Federal Funds Rate before the end of 2015.

After that, the Fed hiked the Federal Funds Rate several times before the rate officially rose to its target range between 2.25% and 2.50%, which lasted until 31 July 2019.

But that wasn't the Fed's only method of conducting its quantitative tightening policies. In late 2017, the Fed began actively reducing its holdings of debt securities issued by U.S. government entities, where some analysts estimate that each $200 billion reduction in the Fed's balance sheet has the equivalent effect of a 0.25% hike in the Federal Funds Rate. Collectively, the Fed's balance sheet reduction quantitative tightening program from September 2017 through July 2019 would have the equivalent effect of increasing the effective level of the Federal Funds Rate by an additional 0.8%.

The following interactive chart shows how these analysts perceive the effect of the Fed's quantitative tightening programs to the U.S. economy has played out since they began in May 2014, as if the Fed had only raised the Federal Funds Rate from its near-zero level at that time. If you're reading this article on a site that republishes our RSS news feed, please click here to access a static version of the chart.

When we substitute the peak QT-adjusted Federal Funds Rate of 6.2% from July 2019 into our recession odds reckoning tool, using the same average 10-Year and 3-Month U.S. Treasury yields we used in the update to the Recession Probability Track above, we find the adjusted probability of recession starting in the U.S. sometime in the next 12 months is 54.5%, or rather, or slightly better than even.

Whether that's the correct way to account for what what the Fed does in the shadows through its quantitative tightening policies remains to be determined, but the extent to which the Fed's policies have an effect on the economy does explain why investors are betting the Fed will be forced to engage in a series of cuts to the Federal Funds Rate and to also restart its quantitative easing programs to mitigate the effects of a new recession to which its policies are believed to have contributed.

That was an interesting alternative scenario to consider for forecasting the probability of recession in the U.S. during the next 12 months. If you have a particular recession risk scenario you would like to consider, please take advantage of our recession odds reckoning tool.

Meanwhile, if you would like to catch up on any of the analysis we've previously presented, here are all the links going back to when we restarted this series back in June 2017.

Previously on Political Calculations

- The Return of the Recession Probability Track

- U.S. Recession Probability Low After Fed's July 2017 Meeting

- U.S. Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up After Fed Does Nothing

- Déjà Vu All Over Again for U.S. Recession Probability

- Recession Probability Ticks Slightly Up as Fed Hikes

- U.S. Recession Risk Minimal (January 2018)

- U.S. Recession Probability Risk Still Minimal

- U.S. Recession Odds Tick Slightly Upward, Remain Very Low

- The Fed Meets, Nothing Happens, Recession Risk Stays Minimal

- Fed Raises Rates, Recession Risk to Rise in Response

- 1 in 91 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before August 2019

- 1 in 63 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before September 2019

- 1 in 54 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before November 2019

- 1 in 42 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before December 2019

- 1 in 26 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before February 2020

- 1 in 16 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before April 2020

- 1 in 14 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before April 2020

- 1 in 13 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before May 2020

- 1 in 12 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before June 2020

- 1 in 11 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before July 2020

- Odds of U.S. Recession Before August 2020 Rise to 1 in 10

- 1 in 10 Chance of U.S. Recession Starting Before August 2020

Labels: recession forecast

How big is the U.S. Federal Reserve's balance sheet? What kind of assets does it hold? What is the value of those assets?

Three questions, the answers for which we've presented in the following two interactive charts! In the first chart below, we show the value of the major asset categories the U.S. Federal Reserve has held on its balance sheet in each week from 18 December 2002 through 14 August 2019, which provides the data needed to answer all three questions. [If you're accessing this article that republishes our RSS news feed, you might consider clicking through to our site to access a working version of the interactive chart, or if you prefer, you can click here for a static version.]

Our second chart presents the same data, but this time in a stacked area format, which makes it easier to find the answer to the first question of how big the Fed's balance sheet has been from 18 December 2002 through 14 August 2019. [Click here for a static version of this second chart.]

Starting at 18 December 2002, the Fed's balance sheet consisted mainly of U.S. Treasuries, which grew from $629 billion at that time to roughly $800 billion in late 2007. The onset of the Great Recession saw the Fed's balance sheet crash to a level of roughly $450 billion by mid-2008, after which the size of the Fed's balance sheet inflated in three major phases through its quantitative easing monetary policy, in which it sought to prop up government supported agencies such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by buying bonds these entities issued to support their operations (Federal Agency Debt), while also buying up the Mortgage Backed Securities these institutions issued to prop up the U.S. housing market. At the same time, the Fed also funded the U.S. government's deficit spending by buying copious amounts of U.S. Treasuries.

By January 2015, the combined amount of all these assets averaged roughly $4.25 trillion, which the Fed held stable at this level until late 2017, when the Fed began actively reducing the amount of its balance sheet holdings through its quantitative tightening monetary policy. Through 14 August 2019, the combined total of these three major asset categories fell to $3.6 trillion, $625 billion less than the average level it held from 2015 through most of 2017.

If we use Morgan Stanley's estimate that each $200 billion reduction in the Fed's balance sheet has the equivalent effect of a 0.25% hike in the Federal Funds Rate, the Fed's active balance sheet reduction quantitative tightening program since late 2017 has had the equivalent effect of increasing the Federal Funds Rate by an additional 0.8% over its official target range of 2.25-2.50% through the end of July 2019.

On 31 July 2019, the Fed acted to cut its target range for the Federal Funds Rate by a quarter percentage point and to suspend its balance sheet reduction program, effective 1 August 2019.

References

U.S. Federal Reserve. U.S. Treasury Securities Held by the Federal Reserve: All Maturities. [Online Database]. Accessed 17 August 2019.

U.S. Federal Reserve. Federal Agency Debt Securities Held by the Federal Reserve: All Maturities. [Online Database]. Accessed 17 August 2019.

U.S. Federal Reserve. Assets: Securities Held Outright: Mortgage-Backed Securities. [Online Database]. Accessed 17 August 2019.

Labels: data visualization, national debt

Every three months, we take a snapshot of the expectations for future earnings in the S&P 500 at approximately the midpoint of the current quarter, shortly after most U.S. firms have announced their previous quarter's earnings.

The earnings outlook for the S&P 500 has weakened since our Spring 2019 edition. The projected trailing year earnings per share for the index in December 2019 has fallen from the $150.96 forecast three months earlier to $146.63 this month.

The oddest thing about this chart is the projected boost to earnings for 2019-Q4. We don't know any reason why Standard & Poor's trailing year earnings is so optimistic in this quarter after deflating so much in the quarters preceding it.

Looking at that optimism even further out, expected earnings for the S&P 500 at the end of 2020 have also weakened, but by a smaller amount, falling from $167.97 to $166.51 per share, where S&P is projecting a sharply upward trajectory.

You can see in the chart how those projections turned out during 2018 and 2019. These will almost certainly be revised downward, sharply, in upcoming quarters.

Data Source

Silverblatt, Howard. Standard & Poor. S&P 500 Earnings and Estimates. [Excel Spreadsheet]. 15 August 2019. Accessed 16 August 2019.

For a week where the full U.S. Treasury yield curve inverted as stock prices were quite volatile, the week didn't end all that much differently than the previous week did.

By the end of the week, the S&P 500 (Index: SPX) was about one percentage point lower than a week earlier, as investors continued splitting their forward-looking attention betweeen 2019-Q4 and 2020-Q1. And while investors flirted with focusing more closely on 2019-Q4 during the week, there wasn't enough in the news to shift it more fully onto that particular point of time in the future.

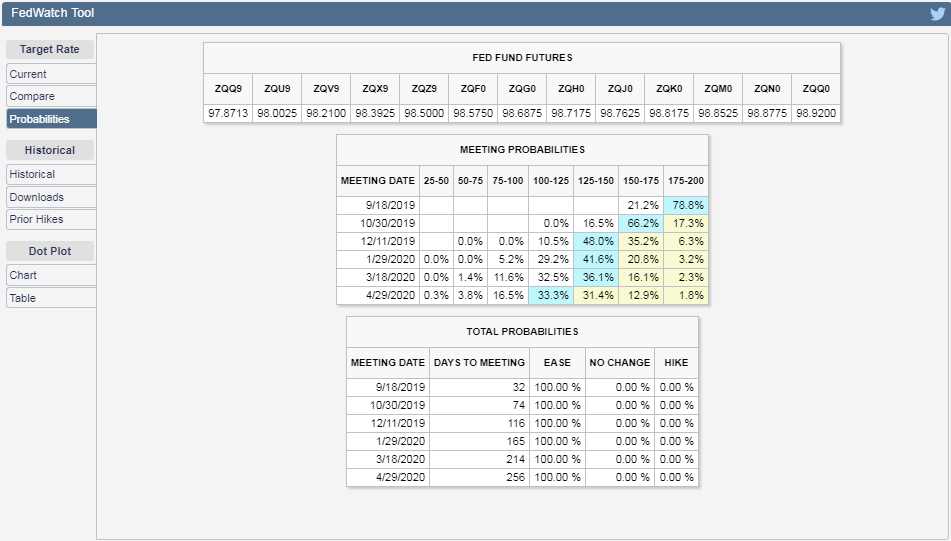

At this point, investors are betting the Federal Reserve will be forced to act aggressively to cut short term interest rates in a bid to revert the yield curve, with the CME Group's FedWatch Tool now projecting as many as four quarter point rate cuts in the four quarters ahead:

We think the uncertainty of the timing of rate cuts between 2019-Q4 and 2020-Q1 is what is holding investors' attention on these two future quarters for now, but the potential deterioration of economic circumstances that would lead to the increased probability of rate cuts extending into 2020-Q2 could spark a much more negative reaction in stock prices should investors have reason to really focus on that particular future quarter.

There's also the potential that changes in the expectations for dividends in any of these upcoming quarters will have an impact on stock prices as well. Fortunately, dividend futures have so far been largely stable, where much of the outsized volatility we've seen may be attributed to investors shifting their time horizons in setting their expectations.

That's why we make a point of tracking the market moving headlines each week, which we've presented below. The random onset of new information plays a large role in setting the forward-looking focus of investors.

- Monday, 12 August 2019

- Oil steadies as Saudi, Kuwait signals offset demand fears

- Bigger trouble developing in China all over:

- China's July new loans dip more than expected, further policy easing seen

- Brazil economic activity index falls in second-quarter, pointing to recession

- Singapore slashes 2019 GDP forecast as global risks expand

- Wall Street falls on geopolitical tensions, recession fears

- Tuesday, 13 August 2019

- Oil soars near 5% as U.S. delays tariffs on some Chinese goods

- Bigger trouble developing in China:

- China July industrial output growth falls to 17-year low as trade war escalates, retail sales disappoint

- China's July steel output eases on environmental curbs, shrinking margins

- China's property investment slows in July as Beijing tightens curbs

- Global motor manufacturing slump hits oil demand: Kemp

- Trump delays tariffs on Chinese cellphones, laptops, toys; markets jump

- Tech leads Wall Street higher as tariff delay sparks rally

- Wednesday, 14 August 2019

- Stocks, oil plunge on growing signs of global slowdown

- Shrinking German economy 'on edge of recession' as exports stutter

- U.S. curve inverts for first time in 12 years; 30-year yield tumbles

- Trump Says Fed Should Cut Rates as Global Growth Concerns Jar Markets

- Yellen says U.S. 'most likely' not entering a recession: FOX Business

- Dow posts biggest one-day drop since October as recession fears take hold

- Thursday, 15 August 2019

- Oil deepens slide on recession fears, China's trade threats

- Trump says China talks 'productive'; Beijing vows tariff retaliation

- U.S. curve inverts for first time in 12 years; 30-year yield tumbles

- U.S. 30-year yields drop to fresh record low below 2%

- 'Crazy inverted yield curve' vexes Fed, with no clear resolution

- S&P 500, Dow gain as upbeat retail sales offset recession fears

- Friday, 16 August 2019

- Oil rises alongside equities, but downbeat OPEC outlook caps gains

- Bigger trouble developing

in Chinaall over: - Hong Kong on brink of recession as trade war, political protests escalate

- Japan exports seen shrinking for eighth month in July, core inflation weak: Reuters poll

- Bigger stimulus developing

in Chinaall over: - To spur consumption, China preps plan to boost disposable income by 2020

- Germany ready to ditch balanced budget in case of recession: Spiegel

- Mexico's central bank cuts rates for first time in 5 years as economy sputters

- China to rely on reforms to lower real interest rates, cabinet says

- Thailand plans $10 billion stimulus to support economy

- Fed minions weighing rate cuts:

- Exclusive: Fed's Mester weighing argument for U.S. rate cut

- Fed's Kashkari says rate cut likely needed to help U.S. economy

- Wall Street ends sharply higher on German stimulus optimism

Looking for the bigger picture of the week's news than the headlines we've noted above? Barry Ritholtz lists seven positives and only five negatives in the week's economics and market-related news.

The U.S. Treasury Department has revised its estimates of the amount of money the U.S. government owed to various foreign countries, which allows us to finalize the data for the government's fiscal 2018 for which we had presented preliminary figures earlier this year.

From the end of its 2017 fiscal year to the end of its 2018 fiscal year, the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding increased by $1,271 billion, or $1.3 trillion, to reach a total of $21,516 billion, or $21.5 trillion. Put a little bit differently, the U.S. national debt grew at an average rate of nearly $3.5 billion per day on every day of the government's 2018 fiscal year.

That's a very large number, but 2018 was only the sixth largest annual increase for the U.S. national debt in terms of nominal U.S. dollars. Larger increases were recorded during President Obama's tenure in office in 2012 ($1,276 billion), 2010 ($1,294 billion), 2011 ($1,300 billion), 2009 ($1,413 billion), and 2016 ($1,423 billion).

So it's not an accident that the U.S. national debt has risen to $21.5 trillion, where these six years combined account for 37% of the official U.S. national debt. But to whom does the U.S. government all that money?

The following chart breaks down who the U.S. government's major creditors were at the end of its 2018 fiscal year, which is based on preliminary data that will be revised in upcoming months.

According to the U.S. Treasury Department, the U.S. government spent some $779 billion more than it collected in taxes during its 2017 fiscal year. The difference between this figure and the $1,271 billion that the total national debt officially rose can be attributed to the government's net borrowing to fund things like Federal Direct Student Loans, which have combined to account for over $1.2 trillion of the government's $21.5 trillion debt, or 5.7% of the total public debt outstanding since 2010.

Overall, 70% of the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding is held by U.S. individuals and institutions, while 30% is held by foreign entities. For FY2018, China has retained its position as the top foreign holder of U.S. government-issued debt, with directly accounting for 5.7% between institutions on the Chinese mainland and Hong Kong, even though the country has been reducing its holdings of U.S. government-issued debt.

Japan ranks as the second largest foreign holder of the U.S. national debt, with the U.S. owing Japanese institutions 5.4% of its total debt. After that, the European international banking centers of Belgium, Ireland, and Luxembourg combine to account for 3.2% of the U.S. national debt, followed by Brazil at 1.5% and the United Kingdom with 1.3%.

The largest single institution holding U.S. government-issued debt is Social Security's Old Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, which is considered to be an "Intragovernmental" holder of the U.S. national debt, and which holds 13.0% of the nation's total public debt outstanding. The share of the national debt held by Social Security's main trust fund has begun to decline as that government agency cashes out its holdings to pay promised levels of Social Security benefits, where its account is expected to be fully depleted in just 16 years. Under current law, after Social Security's trust fund runs out of money in 2034, all Social Security benefits would be reduced by 23% according to the agency's projections.

The largest single "private" institution that has loaned money to the U.S. government is the U.S. Federal Reserve which, like China, has been reducing its holdings of U.S. government-issued debt. At the end of September 2018, the Fed held 12.5% of the U.S. government's total public debt outstanding. In FY2018, other U.S. institutions such as pension funds and insurance companies have significantly increased their holdings of U.S. government-issued debt as interest rates rose during that year.

Data Sources

U.S. Treasury. The Debt To the Penny and Who Holds It. [Online Application]. 28 September 2018.

Federal Reserve Statistical Release. H.4.1. Factors Affecting Reserve Balances. Release Date: 26 September 2018. [Online Document].

U.S. Treasury. Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities. Accessed 15 August 2019.

U.S. Treasury. Monthly Treasury Statement of Receipts and Outlays of the United States Government for Fiscal Year 2018 Through September 30, 2018. [PDF Document].

Labels: national debt

Welcome to the blogosphere's toolchest! Here, unlike other blogs dedicated to analyzing current events, we create easy-to-use, simple tools to do the math related to them so you can get in on the action too! If you would like to learn more about these tools, or if you would like to contribute ideas to develop for this blog, please e-mail us at:

ironman at politicalcalculations

Thanks in advance!

Closing values for previous trading day.

This site is primarily powered by:

CSS Validation

RSS Site Feed

JavaScript

The tools on this site are built using JavaScript. If you would like to learn more, one of the best free resources on the web is available at W3Schools.com.